An international team of researchers has discovered a previously unknown species of dinosaur in western Romania and named it after its location in Transylvania: Transylvanosaurus platycephalus lived about 70 million years ago and was a herbivore.

The news comes from the team led by paleontologist Felix Augustin at the University of Tübingen. The discovery has just been published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Besides Augustin, the study involved scientists from the University of Bucharest and the University of Zurich.

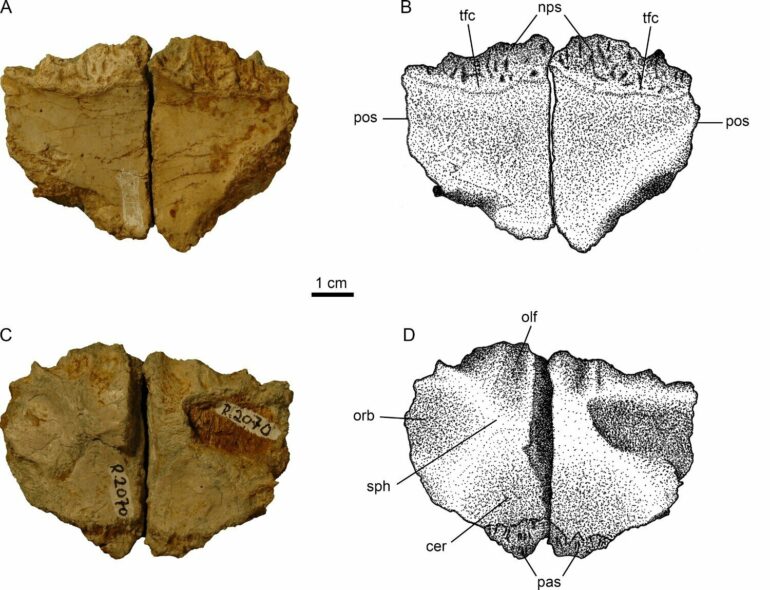

Transylvanosaurus platycephalus literally means “flat-headed reptile from Transylvania.” The previously unknown dinosaur was roughly two meters long, walked on two legs, and belonged to the family of Rhabdodontidae. In Transylvania they, like other local dinosaurs, only reached a small body size and are therefore known as “dwarf dinosaurs.”

The cranial bones of Transylvanosaurus that have been discovered offer deeper insights into the evolution of European faunas shortly before the extinction of dinosaurs 66 million years ago. “Presumably a limited supply of resources in these parts of Europe at that time led to an adapted small body size,” says Augustin.

For most of the Cretaceous period, which lasted from 145 million years to 66 million years ago, Europe was a tropical archipelago. Transylvanosaurus lived on one of the many islands together with other dwarf dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and giant flying pterosaurs which had wingspans of up to ten meters. “With each newly discovered species we are disproving the widespread assumption that the Late Cretaceous fauna had a low diversity in Europe,” says Augustin.

During the Late Cretaceous, the Rhabdodontidae were the most common group of small to medium European herbivores. Related species previously found in the same area had far narrower skulls than Transylvanosaurus. On the other hand, its nearest relatives lived in what is today France—this was a massive surprise to the scientists. How did Transylvanosaurus find its way to the “Island of the Dwarf Dinosaurs” in what is now Transylvania?

In the journal, paleontologists Felix Augustin, his doctoral supervisor Zoltán Csiki-Sava from the University of Bucharest, Dylan Bastiaans from the University of Zurich/ Naturalis Biodiversity Center Leiden, and independent researcher Mihai Dumbravă from Dorset reconstruct various possibilities. The oldest finds assigned to Rhabdodontidae come from Eastern Europe—the animals could have spread westwards from there, and later certain species could have returned to Transylvania.

Fluctuations in sea level and tectonic processes created temporary land bridges between the many islands and could have encouraged these animals to spread, the scientists conjecture. Furthermore, it can be assumed that almost all dinosaurs could swim to an extent, including Transylvanosaurus. “They had powerful legs and a powerful tail. Most species, in particular reptiles, can swim from birth,” says Augustin. Another possibility is that various lines of rhabdodontid species developed in parallel in eastern and western Europe.

Precisely how Transylvanosaurus ended up in the eastern part of the European archipelago remains unclear for now. “We have currently too few data at hand to answer these questions,” says Augustin. The team had only a few bones for the taxonomic classification, and none longer than twelve centimeters: the rear, lower part of the skull with the occipital foramen and two frontal bones. “On the inside of the frontal bone it was even possible to discern the contours of the brain of Transylvanosaurus,” Bastiaans adds.

Zoltán Csiki-Sava and his team from the University of Bucharest found the skull bones of Transylvanosaurus in 2007 in a riverbed of the Haţeg Basin in Transylvania. The Haţeg Basin is one of the most important places for Late Cretaceous vertebrate discoveries in Europe. A total of ten dinosaur species have already been identified there.

“That is unusual. When we do find something, there are often only a few bones; nevertheless, even these can sometimes yield amazing news—such as with Transylvanosaurus now,” says Csiki-Sava. The bones of Transylvanosaurus were able to survive for tens of millions of years because they were protected by the sediments of an ancient riverbed—until another river washed them free again.

“If the dinosaur had died and simply lain on the ground instead of being partly buried, weather and scavengers would soon have destroyed all of its bones and we would never have learned about it,” says Augustin.

More information:

Felix J. Augustin et al, A new ornithopod dinosaur, Transylvanosaurus platycephalus gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria: Ornithischia), from the Upper Cretaceous of the Haţeg Basin, Romania, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2022). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2022.2133610

Provided by

Universitaet Tübingen

Citation:

International team of researchers identifies new species of dinosaur (2022, November 25)