Atmospheric rivers, those long, powerful streams of moisture in the sky, are becoming more frequent in the Arctic, and they’re helping to drive dramatic shrinking of the Arctic’s sea ice cover.

While less ice might have some benefits – it would allow more shipping in winter and access to minerals – sea ice loss also contributes to global warming and to extreme storms that cause economic damage well beyond the Arctic.

I’m an atmospheric scientist. In a new study of the Barents-Kara Seas and the neighboring central Arctic, published Feb. 6, 2023, in Nature Climate Change, my colleagues and I found that these storms reached this region more often and were responsible for over a third of the region’s early winter sea ice decline since 1979.

More frequent atmospheric rivers

By early winter, the temperature in most of the Arctic is well below freezing and the days are mostly dark. Sea ice should be growing and spreading over a wider area. Yet the total area with Arctic sea ice has fallen dramatically in recent decades.

Part of the reason is that atmospheric rivers have been penetrating into the region more frequently in recent decades.

Atmospheric rivers get their name because they are essentially long rivers of water vapor in the sky. They carry heat and water from the subtropical oceans into the midlatitudes and beyond. California and New Zealand both saw extreme rainfall from multiple atmospheric rivers in January 2023. These storms also drive the bulk of moisture reaching the Arctic.

Warm air can hold more water vapor. So as the planet and the Arctic warm, atmospheric rivers and other storms carrying lots of moisture can become more common – including in colder regions like the Arctic.

When atmospheric rivers cross over newly formed sea ice, their heat and rainfall can melt the thin, fragile ice cover away. Ice will start to regrow fairly quickly, but episodic atmospheric river penetrations can easily melt it again. The increasing frequency of these storms means it takes longer for stable ice cover to become established.

As a result, sea ice doesn’t spread to the extent that the cold winter temperature normally would allow it to, leaving more ocean water open longer to release heat energy.

How atmospheric rivers melt sea ice

Atmospheric rivers affect sea ice melting in two primary ways.

More precipitation is falling as rain. But a larger influence on ice loss involves water vapor in the atmosphere. As water vapor turns into rainfall, the process releases a lot of heat, which warms the atmosphere. Water vapor also has a greenhouse effect that prevents heat from escaping into space. Together with the effect of clouds, they make the atmosphere much warmer than the sea ice.

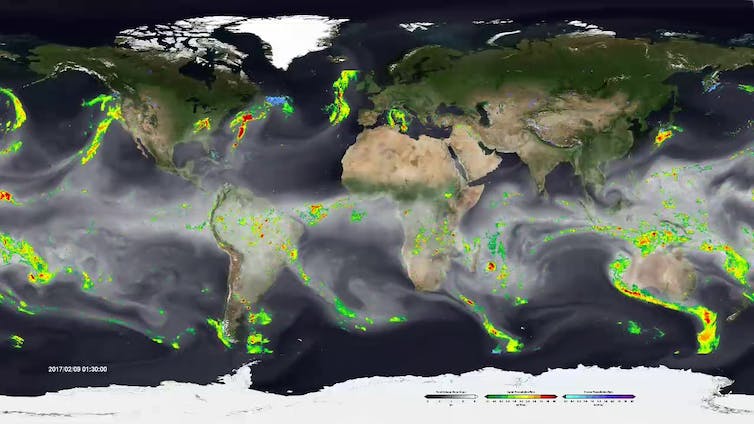

Atmospheric rivers around the world in February 2017.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Scientists have known for years that heat from strong moisture transports could…