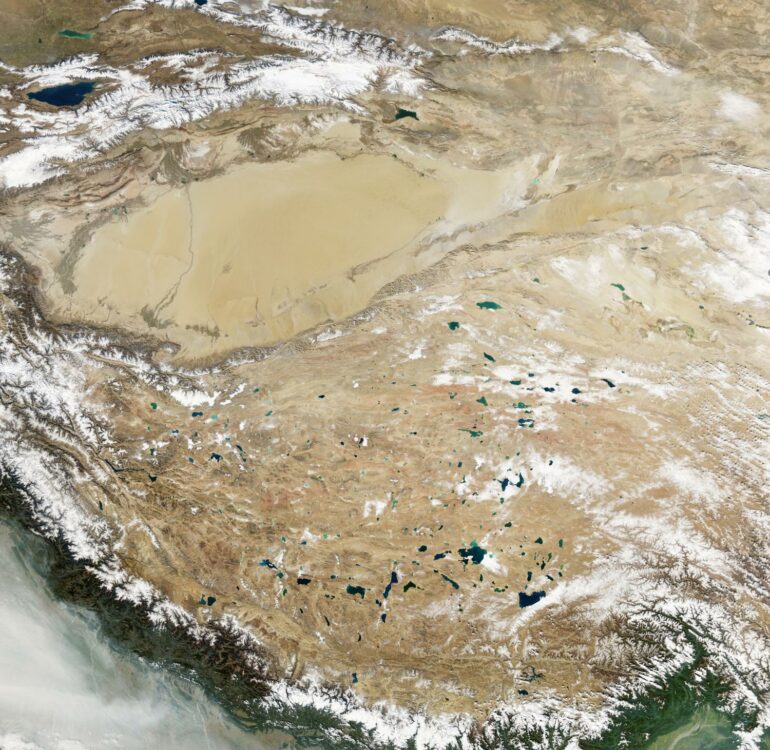

As the highest region on Earth, the Tibetan Plateau engenders the most intriguing myths of Earth system science, provides the most water resources for human survival, and creates the most uncertain legacy for future generations.

The region’s extreme environment kept researchers from probing its wealth of knowledge until the 1970s, when the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) made the first scientific expedition to the region. In 1980, the first International Symposium on the Tibetan Plateau was held, marking the beginning of international collaboration on Tibetan Plateau research, which eventually developed into the Third Pole Environment (TPE), a sponsored flagship program under the auspices of UNESCO, UNEP, SCOPE, and CAS.

“The name ‘Third Pole’ was used to highlight the region’s scientific significance as the third largest reservoir of frozen water after the Arctic and the Antarctic,” said Yao Tandong, an elected member of CAS, who initiated the program with his counterparts Lonnie G. Thompson from the U.S. and Volker Mosbrugger from Germany in 2009. They were later joined by Deliang Chen from Sweden and PIAO Shilong from China.

This science-focused approach of TPE has paid off. According to a recent comment paper in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, “TPE now includes over 300 researchers from 30 countries, with expertise spanning meteorology, hydrology, glaciology, ecology, and paleoclimatology.”

“We built TPE to enable scientists from different countries and across disciplines to compare notes,” said TPE Co-chair Lonnie Thompson from the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, Ohio State University, where ice cores