“The Tale of Genji,” often called Japan’s first novel, was written 1,000 years ago. Yet it still occupies a powerful place in the Japanese imagination. A popular TV drama, “Dear Radiance” – “Hikaru kimi e” – is based on the life of its author, Murasaki Shikibu: the lady-in-waiting whose experiences at court inspired the refined world of “Genji.”

Romantic relationships, poetry and political intrigue provide most of the novel’s action. Yet illness plays an important role in several crucial moments, most famously when one of the main character’s lovers, Yūgao, falls ill and passes away, killed by what appears to be a powerful spirit – as later happens to his wife, Aoi, as well.

Someone reading “The Tale of Genji” at the time it was written would have found this realistic – as would some people in different cultures around the world today. Records from early medieval Japan document numerous descriptions of spirit possession, usually blamed on spirits of the dead. As has been true in many times and places, physical and spiritual health were seen as intertwined.

As a historian of premodern Japan, I’ve studied the processes its healing experts used to deal with possessions, and illness generally. Both literature and historical records demonstrate that the boundaries between what are often called “religion” and “medicine” were indistinct, if they existed at all.

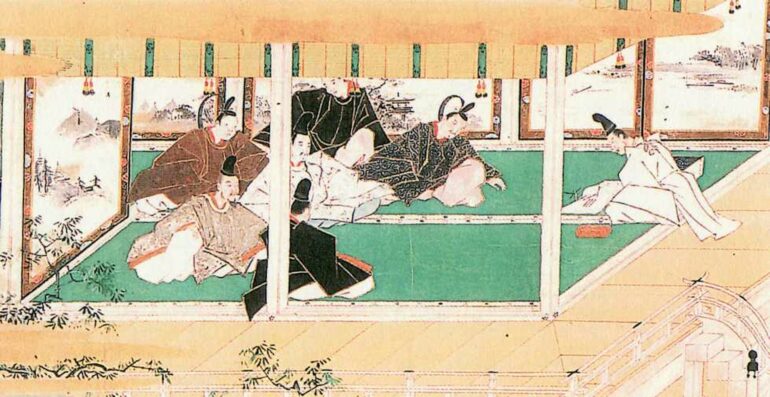

A 17th-century scroll, ‘Maboroshi no Genji monogatari emaki,’ showing the funeral of Genji’s wife, Aoi.

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Vanquishing spirits

The government department in charge of divination, the Bureau of Yin and Yang, established in the late seventh century, played a crucial role. Its technicians, known as onmyōji – yin and yang masters – were in charge of divination and fortunetelling. They were also responsible for observing the skies, interpreting omens, calendrical calculations, timekeeping and eventually a variety of rituals.

Today, onmyōji appear as wizardlike figures in novels, manga, anime and video games. Though heavily fictionalized, there is a historical kernel of truth in these fantastical depictions.

Starting from around the 10th century, Onmyōji were charged with carrying out iatromancy: divining the cause of a disease. Generally, they distinguished between disease caused by external or internal factors, though boundaries between the categories were often blurred. External factors could include local deities known as “kami,” other kami-like entities the patient had upset, minor Buddhist deities or malicious spirits – often revengeful ghosts.

In the case of spirit-induced illness, Buddhist monks would work to winnow out the culprit. Monks who specialized in exorcistic practices were known as “genja” and were believed to know how to expel the spirit from a patient’s body through powerful incantations. Genja would then transfer it…