Understanding why some people trust some scientists more than others is a key factor in solving social problems with science. But little was known about the trust levels across the diverse range of scientific fields and perspectives.

Recognizing this gap, researchers from the University of Amsterdam investigated trust in scientists across 45 fields. They found that, in general, people do trust scientists, but the level of trust varies greatly depending on the scientist’s field, with political scientists and economists being trusted the least. The study is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Scientists are on the front lines of tackling some of the world’s biggest challenges, from climate change and biodiversity loss to pandemics and social inequalities. With these pressing issues at hand, there is a growing expectation that scientists will actively participate in shaping policies that affect us all.

At the same time, concerns have risen about people’s trust in scientists, as not everyone has enough faith in scientists to use their ideas to solve the pressing issues. This lack of trust poses a significant barrier to the implementation of scientific solutions.

From agronomists to zoologists

In their study, involving 2,780 participants from the United States, social psychologists from the University of Amsterdam (led by Ph.D. candidate Vukašin Gligorić) shed light on the factors shaping trust in 45 different types of scientists, from agronomists to zoologists. According to the authors, no other study has yet investigated the trust in such a large number of scientists.

Participants were quizzed on how they see scientists with regard to:

Competence: how clever and intelligent they consider scientists

Assertiveness: how confident and assertive

Morality: how just and fair

Warmth: how friendly and caring

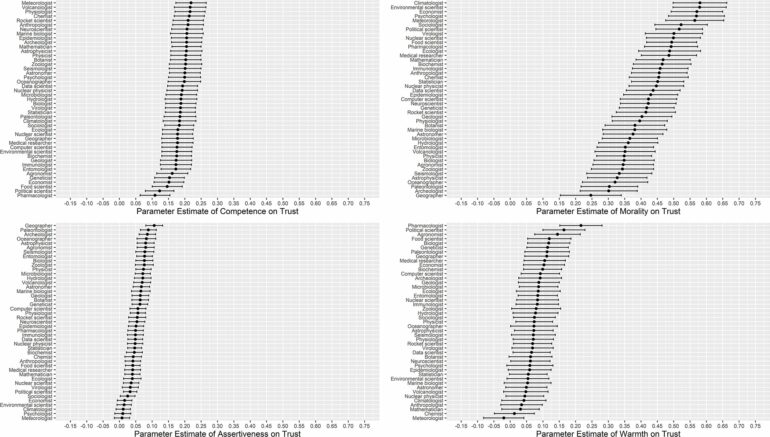

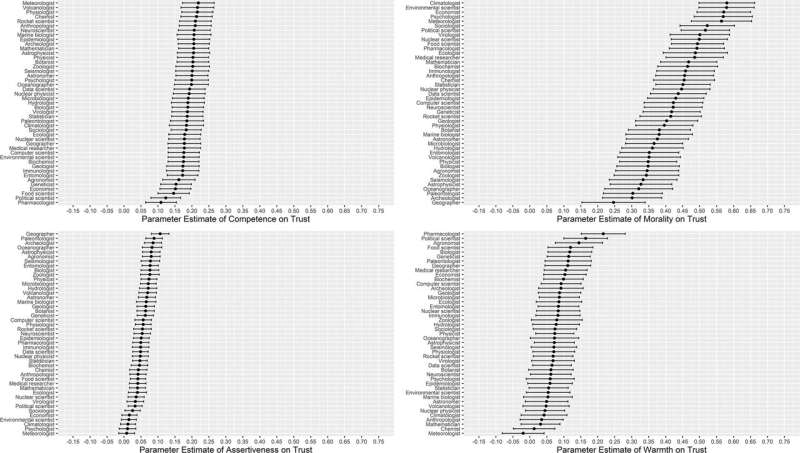

The estimates of competence and assertiveness predicting trust for all 45 scientific occupations. © PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299621

Participants also completed a newly developed Influence Granting Task. This task presented participants with a complex problem and asked them to allocate decision power to different parties like citizens and friends, with one party always including one group of scientists.

Gligorić and colleagues discovered that, overall, people tended to trust scientists. Trust levels, however, varied considerably depending on the scientist’s field of study. For example, on a 7-point scale, with 7 being most trusted and 1 least, political scientists and economists scored a 3.71 and 4.28, respectively, while neuroscientists and marine biologists enjoyed the highest levels of trust, with scores of 5.53 and 5.54, respectively.

Competence and morality

The authors also conclude that there are two major factors that drive trust: perceptions of competence and morality. When people viewed scientists as competent and morally upright, they were more likely to trust them and were then willing to let scientists have a say in solving society’s problems.

Interestingly, the importance of morality in shaping trust varied across different scientific fields. Morality mattered most when it came to trusting scientists working on controversial topics like climate change or social issues, but less so for other scientists such as geographers or archaeologists.

The diversity of scientific fields must be taken into account

The authors say that their study is not only important for understanding how trust in scientists is shaped, but also for understanding what makes people look for scientists’ input in policymaking.

“This study is just the beginning,” says Gligorić. “Future research should explore the generalizability of these findings beyond the U.S. context and delve into the causal relationships between trust and other variables.

“Nevertheless, one thing is clear: the diversity of scientific fields must be taken into account to more precisely map trust, which is important for understanding how scientific solutions can best find their way to policy.”

More information:

Vukašin Gligorić et al, How social evaluations shape trust in 45 types of scientists, PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299621

Provided by

University of Amsterdam

Citation:

How much trust do people have in different types of scientists? (2024, April 25)