When the first modern humans arose in East Africa sometime between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, the world was very different compared to today. Perhaps the biggest difference was that we – meaning people of our species, Homo sapiens – were only one of several types of humans (or hominins) that simultaneously existed on Earth.

From the well-known Neanderthals and more enigmatic Denisovans in Eurasia, to the diminutive “hobbit” Homo floresiensis on the island of Flores in Indonesia, to Homo naledi that lived in South Africa, multiple hominins abounded.

Then, between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago, all but one type of these hominins disappeared, and for the first time we were alone.

Until recently, one of the mysteries about human history was whether our ancestors interacted and mated with these other types of humans before they went extinct. This fascinating question was the subject of great and often contentious debates among scientists for decades, because the data needed to answer this question simply didn’t exist. In fact, it seemed to many that the data would never exist.

Svante Pääbo, however, paid little attention to what people thought was or was not possible. His persistence in developing tools to extract, sequence and interpret ancient DNA enabled sequencing the genomes of Neanderthals, Denisovans and early modern humans who lived over 45,000 years ago.

For developing this new field of paleogenomics, Pääbo was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This honor is not only well-deserved recognition for Pääbo’s triumphs, but also for evolutionary genomics and the insights it can contribute toward a more comprehensive understanding of human health and disease.

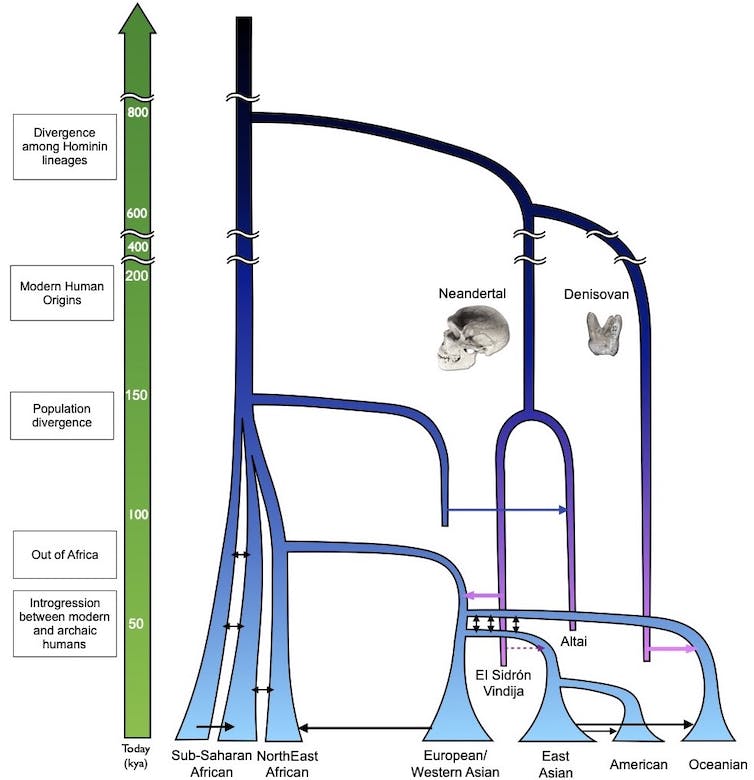

A simplified model of human evolution showing how humans are related to Neanderthals and Denisovans. Arrows between different branches show mating that occurred. Events that happened further back in time are closer to the top of the image.

Joshua Akey, CC BY-ND

Mixing and mating, revealed by DNA

Genetic studies of living people over the past several decades revealed the general contours of human history. Our species arose in Africa, dispersing out from that continent around 60,000 years ago, ultimately spreading to nearly all habitable places on Earth. Other types of humans existed as modern humans migrated throughout the world, but the genetic data showed little evidence that modern humans mated with other hominins.

Over the past decade, however, the study of ancient DNA, recovered from fossils up to around 400,000 years old, has revealed startling new twists and turns in the story of human history.

For example, the Neanderthal genome provided the data necessary to definitively show that humans and Neanderthals mated. Non-African people alive today inherited about 2% of their genomes from Neanderthal ancestors, thanks to this kind of interbreeding.

In one of the biggest surprises, when Pääbo…