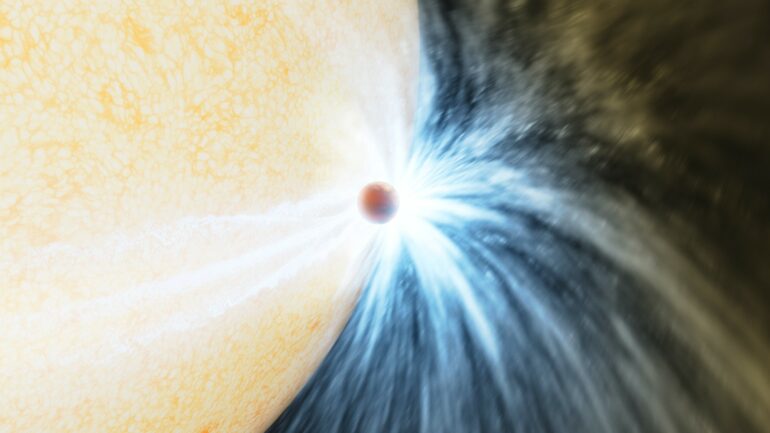

For the first time, astronomers have captured images that show a star consuming one of its planets. The star, named ZTF SLRN-2020, is located in the Milky Way galaxy, in the constellation Aquila. As the star swallowed its planet, the star brightened to 100 times its normal level, allowing the 26-person team of astronomers I worked with to detect this event as it happened.

I am a theoretical astrophysicist, and I developed the computer models that our team uses to interpret the data we collect from telescopes. Although we only see the effects on the star, not the planet directly, our team is confident that the event we witnessed was a star swallowing its planet. Witnessing such an event for the first time has confirmed the long-standing assumption that stars swallow their planets and has illuminated how this fascinating process plays out.

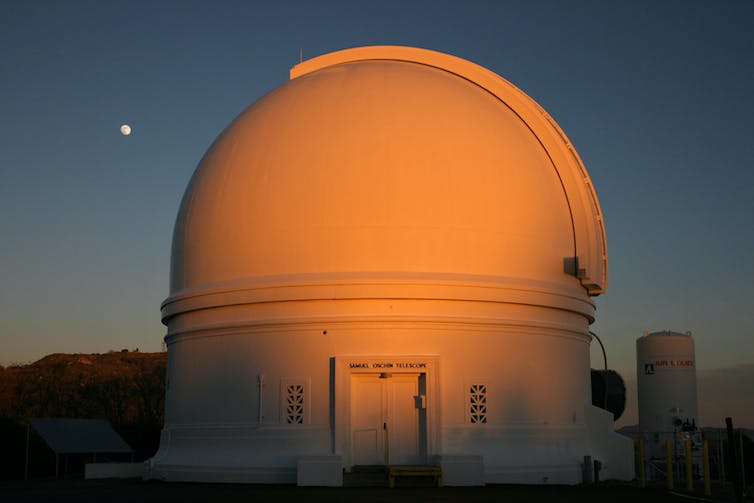

The Zwicky Transient Facility in Southern California is one of the observatories that captured the flash of light caused by the star consuming its planet.

Caltech/Palomar, CC BY-NC

Finding a flash in the dynamic night sky

The team I work with searches for the bursts of light and gas that occur when two stars merge into a bigger, single star. To do this, we have been using data from the Zwicky Transient Facility, a telescope located on Palomar Mountain in Southern California. It takes nightly images of broad swaths of the sky, and astronomers can then compare these images to find stars that change in brightness over time, or what are called astronomical transients.

Finding stars that change in brightness isn’t the challenge – it’s sorting out the cause behind any specific change to a star. As my colleague Kishalay De likes to say, “There are plenty of things in the sky that go boom.” The trick to identifying stellar mergers is to combine visible light – like the data collected at Palomar – with infrared data from NASA’s WISE space telescope, which has been surveying the entire sky for the past decade.

In 2020, the star ZTF SLRN-2020 suddenly became 100 times brighter in visible light over just 10 days. It then slowly started to fade back toward its normal brightness. About nine months before, the same object started to emit a lot of infrared light, too. This is exactly what it looks like when two stars merge together, with one critical difference – everything was scaled down. The brightness and total energy of this event were about a thousand times lower than any of the merging stellar pairs astronomers had found to date.

When a star swallows its planets

The idea that stars could engulf some of their planets has been a long-standing assumption in astronomy. Astronomers have long known that when stars run out of hydrogen in their cores, they get brighter and begin to increase in size.

Many planets have orbits that are smaller than the eventual size of their parent stars. So, when a star runs out of fuel and starts to expand, the planets…