Stars like the Sun are remarkably constant. They vary in brightness by only 0.1% over years and decades, thanks to the fusion of hydrogen into helium that powers them. This process will keep the Sun shining steadily for about 5 billion more years, but when stars exhaust their nuclear fuel, their deaths can lead to pyrotechnics.

The Sun will eventually die by growing large and then condensing into a type of star called a white dwarf. But stars more than eight times more massive than the Sun die violently in an explosion called a supernova.

Supernovae happen across the Milky Way only a few times a century, and these violent explosions are usually remote enough that people here on Earth don’t notice. For a dying star to have any effect on life on our planet, it would have to go supernova within 100 light years from Earth.

I’m an astronomer who studies cosmology and black holes.

In my writing about cosmic endings, I’ve described the threat posed by stellar cataclysms such as supernovae and related phenomena such as gamma-ray bursts. Most of these cataclysms are remote, but when they occur closer to home they can pose a threat to life on Earth.

The death of a massive star

Very few stars are massive enough to die in a supernova. But when one does, it briefly rivals the brightness of billions of stars. At one supernova per 50 years, and with 100 billion galaxies in the universe, somewhere in the universe a supernova explodes every hundredth of a second.

An animation showing a supernova.

The dying star emits high energy radiation as gamma rays. Gamma rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths much shorter than light waves, meaning they’re invisible to the human eye. The dying star also releases a torrent of high-energy particles in the form of cosmic rays: subatomic particles moving at close to the speed of light.

Supernovae in the Milky Way are rare, but a few have been close enough to Earth that historical records discuss them. In 185 A.D., a star appeared in a place where no star had previously been seen. It was probably a supernova.

Observers around the world saw a bright star suddenly appear in 1006 A.D. Astronomers later matched it to a supernova 7,200 light years away. Then, in 1054 A.D., Chinese astronomers recorded a star visible in the daytime sky that astronomers subsequently identified as a supernova 6,500 light years away.

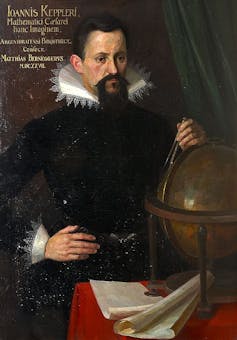

Johannes Kepler, the astronomer who observed what was likely a supernova in 1604.

Kepler-Museum in Weil der Stadt

Johannes Kepler observed the last supernova in the Milky Way in 1604, so in a statistical sense, the next one is overdue.

At 600 light years away, the red supergiant Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion is the nearest massive star getting close to the end of its life. When it goes supernova, it will shine as bright as the full Moon for those…