“I see thy glory like a shooting star.”

So says the Earl of Salisbury as he ruminates about the future in Shakespeare’s “Richard II.”

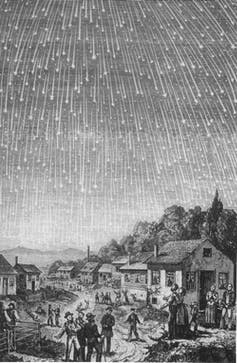

Shooting stars – such as those produced by the Leonid meteor shower depicted in this print from 1889 – are beautiful, but they have nothing to do with real stars.

Adolf Vollmy/WikimediaCommons

During the English Renaissance, people believed shooting stars were luminaries falling from the heavens and harbingers of calamity. But by the end of the 19th century, scientists had established the truth to be far more mundane. What today are commonly called shooting or falling stars are simply small pieces of rock or dust that quickly burn up upon entering Earth’s atmosphere.

But nature has a surprise for you – shooting stars really do exist.

I am an astrophysicist who studies celestial mechanics – how objects like stars, planets and galaxies move.

From 2005 to 2014, a monumental observing program incorporating the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and telescopes at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory confirmed a new class of stars that move with such incredible speed that they can escape the gravity of their home galaxies.

Astronomers are just beginning to understand these real-life shooting stars – called hypervelocity stars – that zoom through the cosmos at millions of miles per hour.

Spinning stars and slingshots

The story of hypervelocity stars begins in 1988, when Jack Gilbert Hills, a theoretician at Los Alamos National Labs, had an inspired idea: What would happen if a binary star system – that is, two stars that are gravitationally bound to each other and orbit a common center of mass – traveled near the massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way? Hills calculated that the tidal force of the black hole could rend the binary system in two.

Imagine two ice skaters holding hands and spinning around until they all of a sudden let go. The two skaters will fly away from each other. Similarly, when two stars in a binary system are wrenched apart by a close encounter with a black hole, they will fly apart. In such an encounter one star might gain enough energy to be slingshotted out of the galaxy entirely.

Astronomers now know that this is how hypervelocity stars are born.

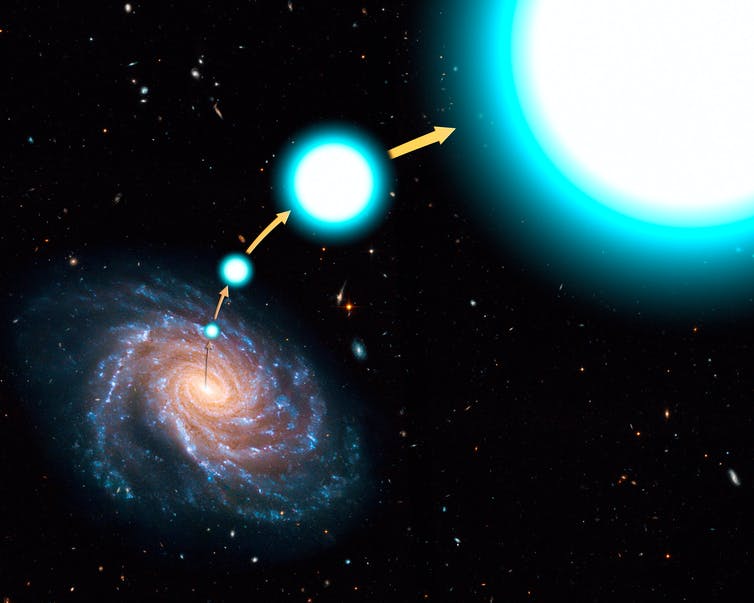

A hypervelocity star, HE 0437-5439, was thrown from the center of the Milky Way and is on a one-way trip out of the galaxy.

NASA, ESA and G. Bacon (STScI), CC BY

Theory, observations and simulations

After the publication of Hills’ prescient paper, the astronomy community considered hypervelocity stars an intriguing possibility, albeit one without observational evidence. That changed in 2005.

While observing stars in the Milky Way’s halo, a team of researchers using the MMT Observatory in Arizona came across something most unexpected. They observed a star escaping the Milky Way at nearly 2 million mph (3.2 million…