Human history was forever changed with the discovery of antibiotics in 1928. Infectious diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and sepsis were widespread and lethal until antibiotics made them treatable. Surgical procedures that once came with a high risk of infection became safer and more routine. Antibiotics marked a triumphant moment in science that transformed medical practice and saved countless lives.

But antibiotics have an inherent caveat: When overused, bacteria can evolve resistance to these drugs. The World Health Organization estimated that these superbugs caused 1.27 million deaths around the world in 2019 and will likely become an increasing threat to global public health in the coming years.

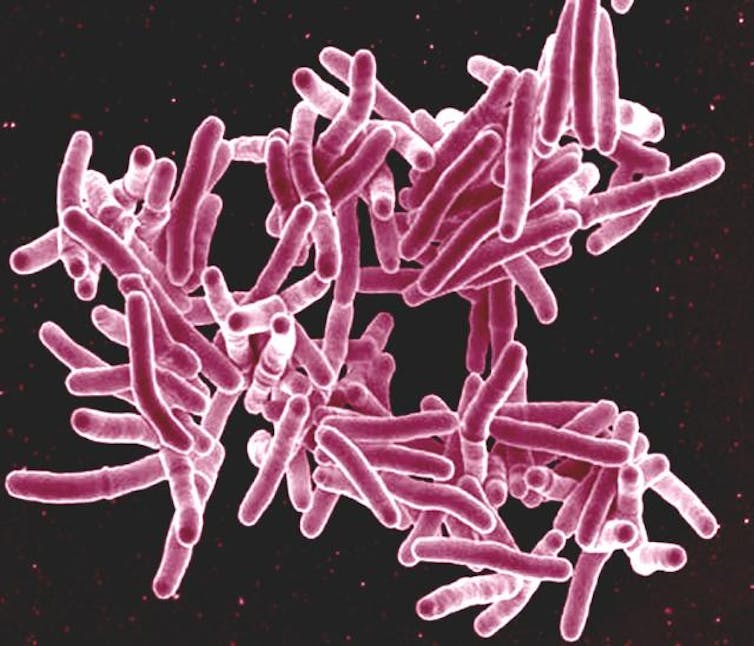

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is one of many microbial species that have developed resistance against multiple antibiotics.

NIAID/Flickr, CC BY

New discoveries are helping scientists face this challenge in innovative ways. Studies have found that nearly a quarter of drugs that aren’t normally prescribed as antibiotics, such as medications used to treat cancer, diabetes and depression, can kill bacteria at doses typically prescribed for people.

Understanding the mechanisms underlying how certain drugs are toxic to bacteria may have far-reaching implications for medicine. If nonantibiotic drugs target bacteria in different ways from standard antibiotics, they could serve as leads in developing new antibiotics. But if nonantibiotics kill bacteria in similar ways to known antibiotics, their prolonged use, such as in the treatment of chronic disease, might inadvertently promote antibiotic resistance.

In our recently published research, my colleagues and I developed a new machine learning method that not only identified how nonantibiotics kill bacteria but can also help find new bacterial targets for antibiotics.

New ways of killing bacteria

Numerous scientists and physicians around the world are tackling the problem of drug resistance, including me and my colleagues in the Mitchell Lab at UMass Chan Medical School. We use the genetics of bacteria to study which mutations make bacteria more resistant or more sensitive to drugs.

When my team and I learned about the widespread antibacterial activity of nonantibiotics, we were consumed by the challenge it posed: figuring out how these drugs kill bacteria.

To answer this question, I used a genetic screening technique my colleagues recently developed to study how anticancer drugs target bacteria. This method identifies which specific genes and cellular processes change when bacteria mutate. Monitoring how these changes influence the survival of bacteria allows researchers to infer the mechanisms these drugs use to kill bacteria.

I collected and analyzed almost 2 million instances of toxicity between 200 drugs and thousands of mutant bacteria. Using a machine learning algorithm I developed to deduce similarities between different drugs, I grouped…