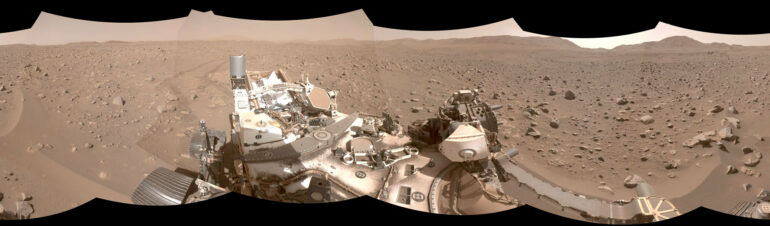

A computer pilot helps NASA’s six-wheeled geologist as it searches for rock samples that could be brought to Earth for deeper investigation.

In about a third of the time it would have taken other NASA Mars rovers, Perseverance recently navigated its way through a field of boulders more than 1,700 feet wide (about a half-kilometer). While planners map out the rover’s general routes, Perseverance managed the finer points of navigating the field, nicknamed “Snowdrift Peak,” on its own, courtesy of AutoNav, the self-driving system that helps cut down driving time between areas of scientific interest.

In fact, Perseverance has set rover speed records on Mars since landing in February 2021. The feats of AutoNav were detailed in a paper about the rover’s autonomous systems published in the July issue of the journal Science Robotics.

Tyler Del Sesto has worked on the software for Perseverance’s AutoNav for seven years. He used to think that sometimes the obstacles placed before Perseverance’s Earthly twin OPTIMISM during testing in the Mars Yard at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory went a little overboard. He changed his mind after Snowdrift Peak.

“It was much denser than anything Perseverance has encountered before—just absolutely littered with these big rocks,” said Del Sesto, deputy rover planner lead for Perseverance at JPL in Southern California. “We didn’t want to go around it because it would have taken us weeks. More time driving means less time for science, so we just dove right in.”

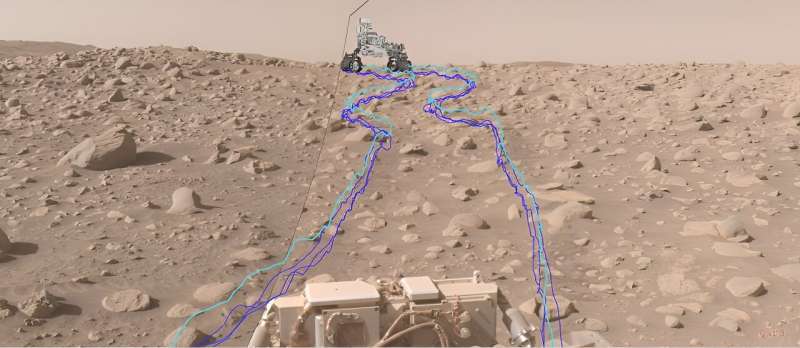

On June 26, Perseverance entered the eastern edge of Snowdrift Peak. Including two stops for boulders that the science team wanted to inspect, the straight-line route through Snowdrift would cover 1,706 feet (520 meters). By the time the rover exited the western edge of the boulder field on July 31, it had logged 2,490 feet (759 meters)—with much of the extra distance coming from AutoNav maneuvering around rocks not visible in the orbiter images used to plan the route.

“If you take out the sols (Martian days) dedicated to mission science, the traverse through Snowdrift Peak only took six autonomous drive sols, which is probably 12 sols faster than Curiosity would have taken,” said Del Sesto. “Of course, everybody on the team knows we only got to this level of performance by standing on the shoulders of giants. Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity were the trailblazers.”

On the wheels of giants

Some form of silicon-based navigator has been in use since the first Mars rover started dodging rocks in 1997. Back then, the microwave oven-size Sojourner needed to stop every 5.1 inches (13 centimeters) for its computer brain to take stock of its new environs before proceeding farther. The next Mars rovers—the golf cart-size Spirit and Opportunity (which arrived in 2004)—could drive distances up to 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) before they too had to halt and figure out next moves.

Curiosity, which landed in 2012, recently got a software upgrade to help make driving decisions, but Perseverance packs several advantages: With faster cameras, the rover can take images quickly enough to process its route in real-time, and it has an additional computer dedicated entirely to image processing, eliminating the need to pause to decide its next move.

“Our rover is the perfect example of the old adage ‘two brains are better than one,'” said Vandi Verma, lead author of the paper and the mission’s chief engineer for robotic operations at JPL. “Perseverance is the first rover that has two computer brains working together, allowing it to make decisions on the fly.”

This autonomous capability has allowed Perseverance to set new records for Mars off-roading, including a single-day drive distance of 1140.7 feet (347.7 meters) and longest drive without human review: 2296.2 feet (699.9 meters). But those achievements took place back when the rover was driving across the relatively flat terrain of Jezero Crater’s floor, without large rocks and other craters standing in its way. That’s why this recent navigation of boulder-festooned Snowdrift Peak impressed even the engineers who plan rover outings.

This composite image, acquired June 29 and annotated at JPL using visualization software, shows Perseverance’s path through a dense section of boulders. The pale blue line indicates the course of the center of the front wheel hubs, while darker blue lines show the paths of the rover’s six wheels. © NASA/JPL-Caltech

New campaign new terrain

While the boulder field may be in Perseverance’s metaphorical rearview mirror, more driving challenges lay ahead. The rover began its fourth science campaign on Sept. 7 by crossing “Mandu Wall,” a rolling ridgeline separating two geologic units along the inner edge of Jezero Crater’s western rim. Orbital data indicates the area is filled with carbonates—which may provide invaluable data on Mars’ environmental history as well as preserve signs of ancient microbial life, if any existed in the area.

“The time where a rover science team could look at features on the Martian horizon and file them away for future consideration is over,” said Ken Farley, Perseverance project scientist at Caltech in Pasadena. “We have to be on our toes because Perseverance’s autonomous capabilities can make something we see in the distance on one sol right in front—or even behind us—on the next.”

With the new exploration possibilities come new challenges: broken bedrock, higher slopes, and sand dunes, as well as small impact craters in Perseverance’s near future.

“This new terrain is definitely going to throw a few curveballs at us and AutoNav,” said Mark Maimone, deputy team chief for robotic operations on Perseverance. “But that is where the science is. We’re ready.”

More information:

Vandi Verma et al, Autonomous robotics is driving Perseverance rover’s progress on Mars, Science Robotics (2023). DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.adi3099

Citation:

Autonomous systems help NASA’s Perseverance do more science on Mars (2023, September 21)