Sperm are the most diverse and rapidly evolving cell type. Why sperm have undergone such dramatic evolution is a mystery that has stumped biologists for more than a century.

To solve this evolutionary puzzle, researchers at Syracuse University’s Center for Reproductive Evolution (CRE) have spent decades studying the mating biology of fruit flies. These small and outwardly unremarkable insects conceal a grand reproductive secret inside: giant sperm.

Fruit flies show more variation in sperm length than do the remainder of the entire animal kingdom combined. For example, males of one species of fruit fly, Drosophila bifurca, inseminate their partners with only a couple dozen sperm, each one being a gargantuan 5.8 cm long (about 20 times longer than the female’s body) and rolled up like a ball of yarn.

Investigations by SU’s Center for Reproductive Evolution members, including Weeden Professor of Biology Scott Pitnick, Professor of Biology Steve Dorus, Assistant Professor of Biology Yasir Ahmed-Braimah and their students have revealed that longer sperm have been favored by sexual selection, for which the theoretical groundwork was laid out by Charles Darwin in 1871 in his seminal book, “The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex.”

Essentially, long sperm tails have evolved because they are better equipped than shorter sperm for the battle to fertilize eggs and because female reproductive tracts are designed to bias fertilization in favor of longer sperm.

In other words, long sperm tails are the cellular, post-mating equivalent of peacock tails. In fact, a previous publication from the Center for Research Evolution in the journal Nature showed that fruit fly sperm tails rival pheasant tail feathers, deer antlers, dung beetle horns, lizard dewlaps and others from the hitlist of nature’s sexiest ornaments and most intimidating weapons.

The ability to test the foundations of sexual selection theory, and to develop new hypotheses about the evolution of sexual traits, has been hampered by limited information about the genetics underlying such traits.

However, in a new study by the Center for Reproductive Evolution, in collaboration with scientists from Stanford University, Cornell University, Virginia Tech, and the University of Zurich shines a light on the genetics of fruit fly sperm length and of the female reproductive organ responsible for its evolution.

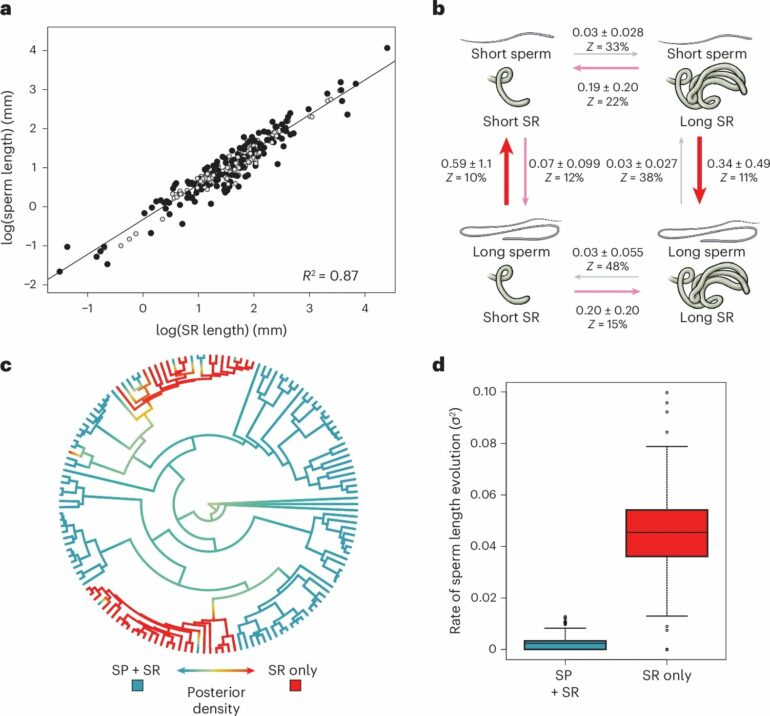

Their findings, published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, may advance our understanding of all mate preferences and sexual ornaments. The research team first measured sperm length and the length of the female seminal receptacle (SR), which is the anatomical basis of female “sperm choice,” in 149 species of fruit flies.

After sequencing the full genomes of every one of these species (published in PLOS Biology), the investigators mapped traits onto the fruit fly tree of life to reveal how these interacting male and female traits have coevolved over the last 65 million years.

Next, the investigators conducted a “genome-wide association study” approach to identify candidate genes underlying variation in sperm and SR length in the lab model fly Drosophila melanogaster. Surprisingly, only about 19% of the genes determining variation in sperm length showed biased expression in the testes and are known to code for spermatogenesis.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Most of the identified genes that code for sperm length are primarily responsible for the development and functioning of the central nervous system, in addition to vision and olfaction. Sperm length genetic variation was also correlated with female lifetime fecundity, starvation resistance, and the ability to find food.

In other words, through the evolution of reproductive tracts designed to give males with longer sperm an advantage in the competition to fertilize their eggs, sexual selection has provided females with a means to comparatively shop around for “good genes”—those enhancing survival and reproduction—to pass on to their offspring.

Finally, a complex algorithm (and approximately 15 million hours of computing time on Syracuse University’s OrangeGrid computing network) was used to identify genes for which the rate of nucleotide sequence evolution significantly correlates with sperm and SR length evolution across the species tree. This approach reinforced the genetic overlap between sperm length and nervous system development and function.

This highly integrative approach holds great promise, not just to expand researchers’ understanding of the evolutionary genetics of sperm, but of fundamental aspects of biodiversity.

More information:

Zeeshan A. Syed et al, Genomics of a sexually selected sperm ornament and female preference in Drosophila, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02587-2

Provided by

Syracuse University

Citation:

Fruit fly study offers new insights into sperm evolution (2024, November 26)