CD163 might not be the most exciting name in the world, but behind it lies one of the body’s most important defense receptors, which steps in when red blood cells break down and release harmful hemoglobin. Now, researchers at Aarhus University are the first in the world to have mapped how CD163 functions. The findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

When infections such as malaria take hold in the body, red blood cells can be severely affected and risk breaking down. When that happens, hemoglobin is released into the bloodstream, potentially causing oxidative damage.

The damage occurs because cells are exposed to reactive oxygen molecules, which form in the bloodstream when oxygen comes into contact with free hemoglobin. If the body is exposed to excessive oxidative damage, it can cause blood vessel damage, kidney failure, inflammation, blood clots and cell death in vital organs.

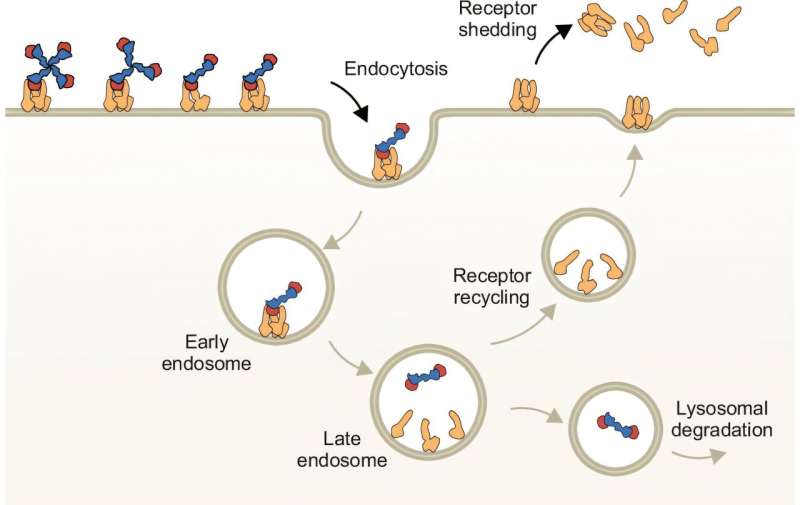

Fortunately, the body has a rescue team at the ready. It consists of the blood protein haptoglobin, which binds to and neutralizes hemoglobin, and the receptor CD163, which sits on the surface of macrophages. CD163’s role is to bind the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex, which is then taken up by the macrophage and broken down inside the cell. But exactly how CD163 binds and takes up the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex is something researchers have only just begun to understand.

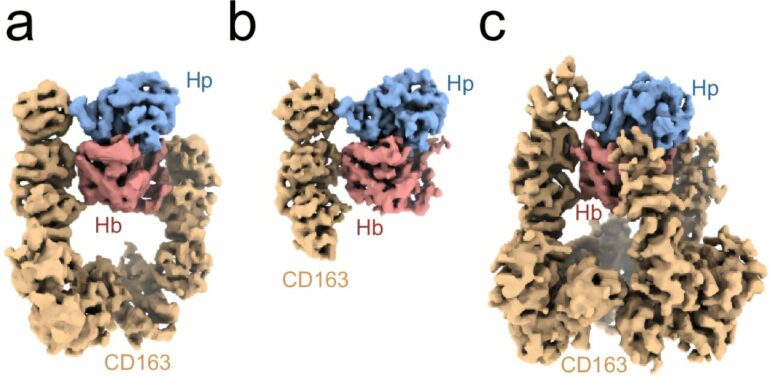

Researchers at the Department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University are the first in the world to uncover the precise structure of CD163 bound to the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex, providing unique insight into how the receptor functions.

Proposed mechanism of CD163-mediated endocytosis of Hb-bound Hp oligomers. © Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-55171-4

This is not the first time Associate Professor Christian Brix Folsted Andersen and his research group have studied the body’s defense against hemoglobin, but this study digs a little deeper, he explains, “We have previously described how the protein haptoglobin binds to hemoglobin and prevents it from causing damage in the bloodstream. What we see in our new research is how the unique structure of CD163 enables the body to effectively recognize, bind and take up the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex. This is an important breakthrough because it connects earlier functional and structural observations.”

The research also opens up a broad range of opportunities, says Associate Professor Christian Brix Folsted Andersen, “Now we can delve into how the structure and function of CD163 have evolved over time, and whether similar mechanisms exist in other species. At the same time, it may be relevant to analyze how CD163 interacts with other proteins and molecules in the body, and what factors regulate its activity.”

More information:

Anders Etzerodt et al, The Cryo-EM structure of human CD163 bound to haptoglobin-hemoglobin reveals molecular mechanisms of hemoglobin scavenging, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-55171-4

Citation:

Critical blood defense receptor CD163 mapped for first time (2025, March 27)