Neuroscientists have long assumed that neurons are greedy, hungry units that demand more energy when they become more active, and the circulatory system complies by providing as much blood as they require to fuel their activity. Indeed, as neuronal activity increases in response to a task, blood flow to that part of the brain increases even more than its rate of energy use, leading to a surplus. This increase is the basis of common functional imaging technology that generates colored maps of brain activity.

Scientists used to interpret this apparent mismatch in blood flow and energy demand as evidence that there is no shortage of blood supply to the brain. The idea of a nonlimited supply was based on the observation that only about 40% of the oxygen delivered to each part of the brain is used – and this percentage actually drops as parts of the brain become more active. It seemed to make evolutionary sense: The brain would have evolved this faster-than-needed increase in blood flow as a safety feature that guarantees sufficient oxygen delivery at all times.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging is one of several ways to measure the brain.

But does blood distribution in the brain actually support a demand-based system? As a neuroscientist myself, I had previously examined a number of other assumptions about the most basic facts about brains and found that they didn’t pan out. To name a few: Human brains don’t have 100 billion neurons, though they do have the most cortical neurons of any species; the degree of folding of the cerebral cortex does not indicate how many neurons are present; and it’s not larger animals that live longer, but those with more neurons in their cortex.

I believe that figuring out what determines blood supply to the brain is essential to understanding how brains work in health and disease. It’s like how cities need to figure out whether the current electrical grid will be enough to support a future population increase. Brains, like cities, only work if they have enough energy supplied.

Resources as highways or rivers

But how could I test whether blood flow to the brain is truly demand-based? My freezers were stocked with preserved, dead brains. How do you study energy use in a brain that is not using energy anymore?

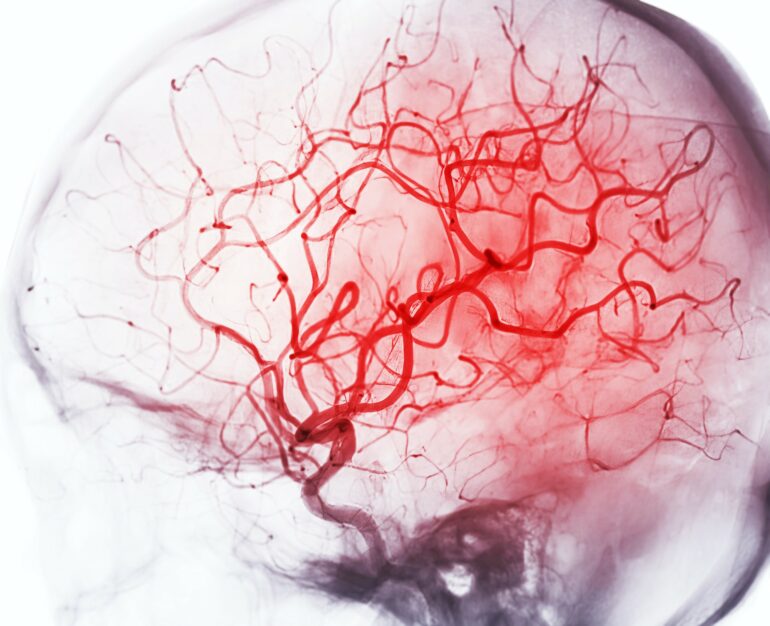

Luckily, the brain leaves behind evidence of its energy use through the pattern of the vessels that distribute blood throughout it. I figured I could look at the density of capillaries – the thin, one-cell-wide vessels that transfer gases, glucose and metabolites between brain and blood. These capillary networks would be preserved in the brains in my freezers.

A demand-based brain should be comparable to a road system. If arteries and veins are the major highways that carry goods to the town of specific parts of the brain, capillaries are akin to the neighborhood streets that actually deliver goods to their final…