The Atlantic hurricane season starts on June 1, and forecasters are keeping a close eye on rising ocean temperatures, and not just in the Atlantic.

Globally, warm sea surface temperatures that can fuel hurricanes have been off the charts in the spring of 2023, but what really matters for Atlantic hurricanes are the ocean temperatures in two locations: the North Atlantic basin, where hurricanes are born and intensify, and the eastern-central tropical Pacific Ocean, where El Niño forms.

This year, the two are in conflict – and likely to exert counteracting influences on the crucial conditions that can make or break an Atlantic hurricane season. The result could be good news for the Caribbean and Atlantic coasts: a near-average hurricane season. But forecasters are warning that the hurricane forecast hinges on El Niño’s panning out.

Ingredients of a hurricane

In general, hurricanes are more likely to form and intensify when a tropical low-pressure system encounters an environment with warm upper-ocean temperatures, moisture in the atmosphere, instability and weak vertical wind shear.

Warm ocean temperatures provide energy for a hurricane to develop. Vertical wind shear, or the difference in the strength and direction of winds between the lower and upper regions of a tropical storm, disrupts the organization of convection – the thunderstorms – and brings dry air into the storm, inhibiting its growth.

How hurricanes form.

The Atlantic Ocean’s role

The Atlantic Ocean’s role is pretty straightforward. Hurricanes draw energy from warm ocean water beneath them. The warmer the ocean temperatures, the better for hurricanes, all else being equal.

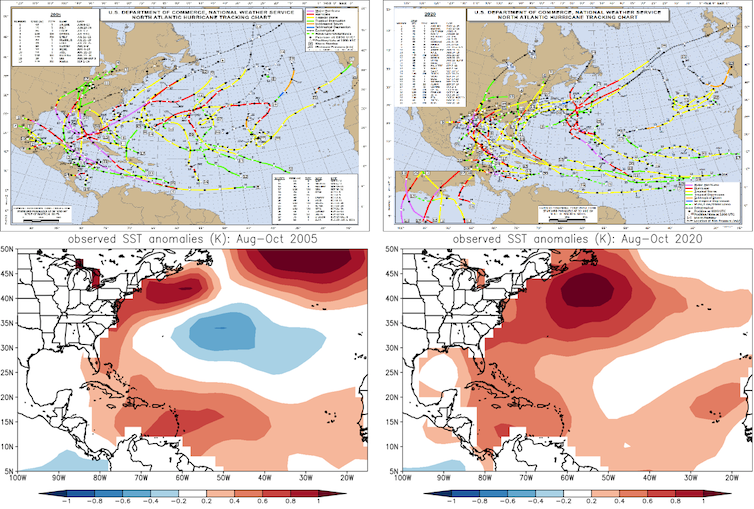

Tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures were unusually warm during the most active Atlantic hurricane seasons on recent record. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season produced a record 30 named tropical cyclones, while the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season produced 28 named storms, a record 15 of which became hurricanes, including Katrina.

The top images show where Atlantic tropical storms traveled in 2005, on the left, and in 2020, on the right. The lower images show the corresponding sea surface temperature anomalies for the August-October peak of the hurricane season compared with the August-October 1991-2020 average in degrees Celsius.

NOAA

How the Pacific Ocean gets involved

The tropical Pacific Ocean’s role in Atlantic hurricane formation is more complicated.

You may be wondering, how can ocean temperatures on the other side of the Americas influence Atlantic hurricanes? The answer lies in teleconnections. A teleconnection is a chain of processes in which a change in the ocean or atmosphere in one region leads to large-scale changes in atmospheric circulation and temperature that can influence the weather elsewhere.