El Niño is officially here, and while it’s still weak right now, federal forecasters expect this global disrupter of worldwide weather patterns to gradually strengthen.

That may sound ominous, but El Niño – Spanish for “the little boy” – is not malevolent, or even automatically bad.

Here’s what forecasters expect, and what it means for the U.S.

What is El Niño?

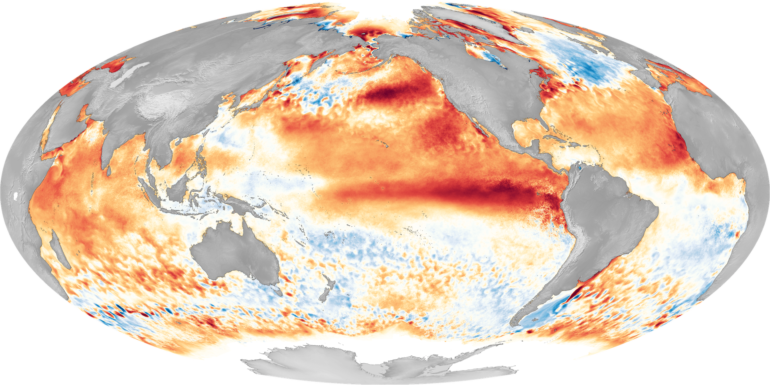

El Niño is a climate pattern that starts with warm water building up in the tropical Pacific west of South America. This happens every three to seven years or so. It might last a few months or a couple of years.

Normally, the trade winds push warm water away from the coast there, allowing cooler water to surface. But when the trade winds weaken, water near the equator can heat up, and that can have all kinds of effects through what are known as teleconnections. The ocean is so vast – covering approximately one-third of the planet, or about 15 times the size of the U.S. – that those sloshings of warm water have knock-on effects around the globe.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explains teleconnections and the impact of El Niño.

That warming at the equator during El Niño leads to the warming of the stratosphere, starting about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) above the surface. Scientists are still studying how exactly this teleconnection occurs.

At the same time, the lower tropical stratosphere cools.

That combination can shift the upper-level winds known as the jet stream, which blow from west to east. Altering the jet stream can affect all kinds of weather variables, from temperatures to storms and winds that can tear hurricanes apart.

Basically, what happens in the Pacific doesn’t stay in the Pacific.

So, what does all that mean for you and me?

With apologies to Charles Dickens, El Niño tends to create a tale of two regions: the best of times for some, and the worst of times for others.

On average, El Niño years are warmer globally than La Niña years – El Niño’s opposite. Globally, a strong El Niño can boost temperatures by about 0.7 degrees Fahrenheit (0.4 Celsius). But in North America, there is a lot of local variation.

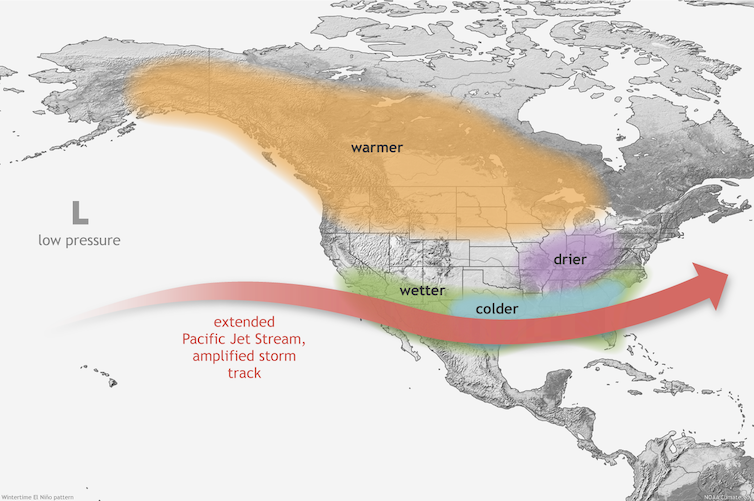

El Niño years tend to be warmer across the northern part of the U.S. and in Canada, and the Pacific Northwest and Ohio Valley are often drier than usual in the winter and fall. The Southwest, on the other hand, tends to be cooler and wetter than average.

El Niño typically shifts the jet stream farther south, so it blows pretty much due west to east over the southern U.S. That shift tends to block moisture from the Gulf of Mexico, reducing the fuel for thunderstorms in the Southeast. La Niña, conversely, is associated with a more wavy and northward-shifted jet stream, which can enhance severe weather activity in the South and Southeast.

El Niño’s typical effects in winter.

NOAA

El…