Between music, podcasts, gaming and the unlimited supply of online content, most people spend hours a week wearing headphones. Perhaps you are considering a new pair for the holidays, but with so many options on the market, it can be hard to know what to choose.

I am a professional musician and a professor of music technology who studies acoustics. My work investigates the intersection between the scientific, artistic and subjective human elements of sound. Choosing the right headphones involves considering all three of those aspects, so what makes for a truly good pair?

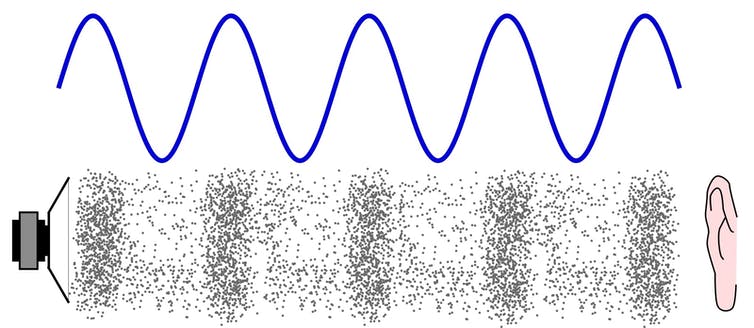

Sound is simply a series of low pressure and high pressure areas where air molecules, represented by the small dots, compress or spread apart.

Pluke/WikimediaCommons

What is sound really?

In physics, sound is made of air vibrations consisting of a series of high and low pressure zones. These are the cycles of a sound wave.

Counting the number of cycles that occur per second determines the frequency, or pitch, of the sound. Higher frequencies mean higher pitches. Scientists describe frequencies in hertz, so a 500 Hz sound goes through 500 complete cycles of low pressure and high pressure per second.

The loudness, or amplitude, of a sound is determined by the maximum pressure of a wave. The higher the pressure, the louder the sound.

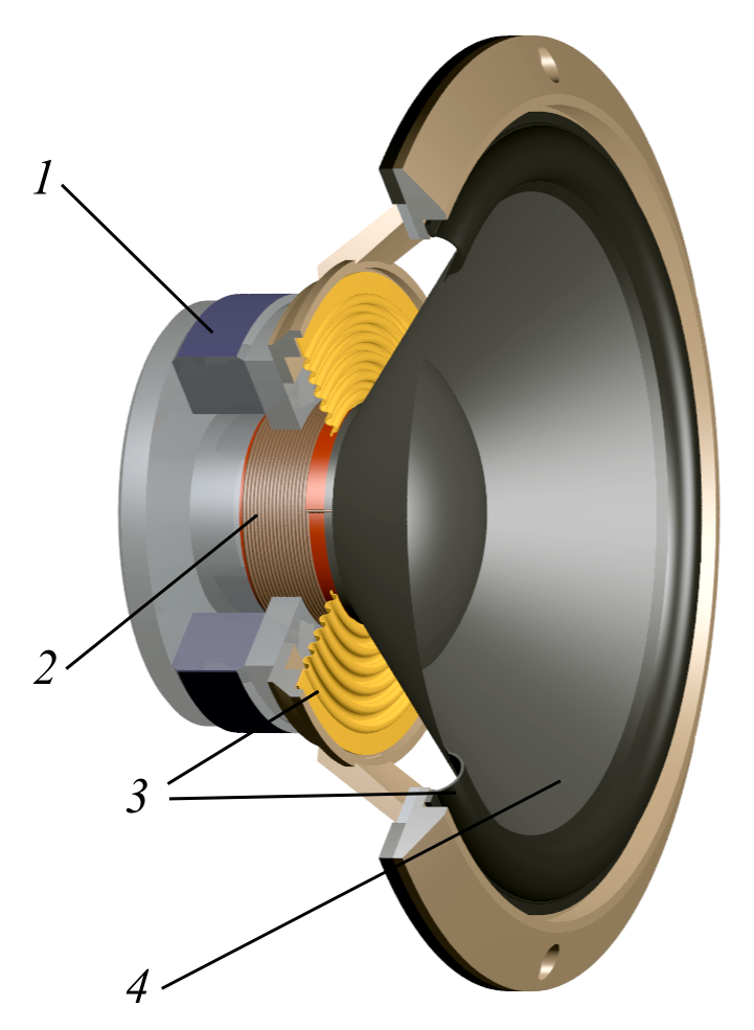

To create sound, headphones turn an electrical audio signal into these cycles of high and low pressure that our ears interpret as sound.

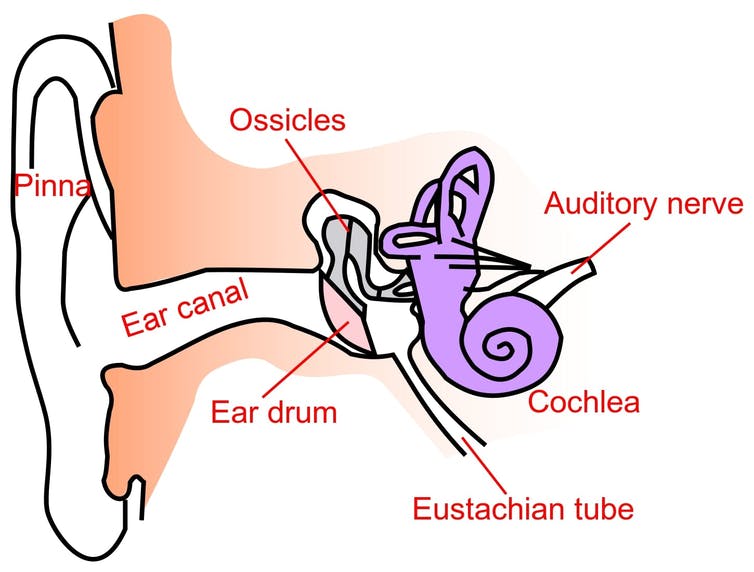

The human ear is a complex system that turns vibrations in the air into electrical signals that go to the brain.

Iain/WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA

The human ear

Human ears are incredible sensors. The average person can hear a huge range of pitches and different levels of loudness. So how does the ear work?

When sound enters your ear, your eardrum translates the air vibrations into mechanical vibrations of the tiny middle ear bones. These mechanical vibrations become fluid vibrations in your inner ear. Sensitive nerves then turn those vibrations into electrical signals that your brain interprets as sound.

Although people can hear a range of pitches roughly from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz, human hearing does not respond equally well at all frequencies.

For example, if a low frequency rumble and a higher pitched bird have the same loudness, you would actually perceive the rumble to be quieter than the bird. Generally speaking, the human ear is more sensitive to middle frequencies than low or high pitches. Researchers think this may be due to evolutionary factors.

Most people don’t know that hearing sensitivity varies and, frankly, would never need to consider this phenomenon – it is simply how people hear. But headphone engineers definitely need to consider how human perception differs from pure physics.