The legendary robbers Schinderhannes and Schwarzer Jonas were executed by guillotine in Mainz in 1803. In 1805, the first chairholder of anatomy at the University of Heidelberg, Jacob Fidelis Ackermann, brought the two skeletons to his institute, where they were subsequently mixed up. An international research team has now been able to clear up this error using the latest analytical methods and conclusively identify the skeleton of Schinderhannes. The scientists have now published their results in the journal Forensic Science International: Genetics.

For 220 years, they have been part of the Anatomical Collection at the University of Heidelberg: two skeletons labeled with the names of the legendary German robbers Johannes Bückler, better known as Schinderhannes and Schwarzer Jonas (Black Jonas). Both men were guillotined in November 1803 in Mainz along with 18 other convicts. The first incumbent of the Chair of Anatomy and Physiology in Heidelberg, Jacob Fidelis Ackermann, brought the skeletons to Heidelberg in 1805. However, apparently under Ackermann’s successor Friedrich Tiedemann, the collection numbers were mixed up at the beginning of the 19th century—and that’s when the skeletons were misattributed.

An international research team led by Dr. Sara Doll, Institute of Anatomy and Cell Biology at the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University and curator of the anatomical collection, and Professor Dr. Walther Parson, head of the Forensic Molecular Biology research unit at the Institute of Legal Medicine at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, combined various analytical methods in the study and were able to show that the supposed skeleton of Black Jonas clearly belonged to Schinderhannes. The alleged skeleton of Schinderhannes, on the other hand, is not that of Schwarzer Jonas.

Since the numbers of the bone montages were obviously assigned incorrectly at the beginning of the 19th century, the actual skeleton of Schwarzer Jonas was lost over time. “It is possible that it was stolen or borrowed in the belief that it was the skeleton of Schinderhannes’ and was never returned? Ironically, this mix-up could ultimately have led to our still being in possession of the real skeleton of Schinderhannes’ today,” says Dr. Sara Doll.

Genetic reconstruction of eye, hair and skin color

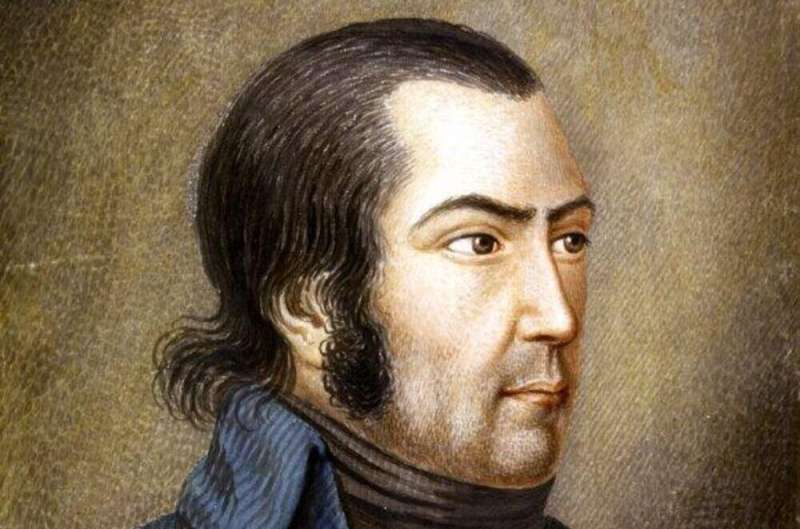

There are only a few, sometimes contradictory, contemporary descriptions of Schinderhannes’ appearance. The few surviving images—such as engravings or paintings—were mostly created after his death and are based more on artistic license than on authentic models. In addition to the unequivocal attribution of his skeleton, genetic analyses have now also allowed the determination of his eye, hair and skin color, thus clarifying the contradictory literary situation for future scientific and cultural projects.

“The data suggests that Schinderhannes had brown eyes, dark hair and rather pale skin,” explains Professor Dr. Parson, who analyzed the data.

Painter and graphic artist Karl Matthias Ernst also portrayed the robber Christian Reinhard, known as ‘Schwarzen Jonas’ (Black Jonas), in 1803. © Stadtarchiv Mainz BPSP/3900 C

Step by step to the solution of the mystery

Thanks to the interdisciplinary work, in which researchers from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Portugal and the U.S. were involved, the scientists were able to narrow down the identities of the skeletons more and more: Using isotope analysis, in which experts analyze different types of atoms of the same chemical element, e.g. in bones, they were able to determine, among other things, where the two individuals presumably spent their childhood and later years—in the case of Schinderhannes, the Hunsrück area is a possibility.

Further anthropological examinations, e.g. chemical analyses of the bones, and radiological imaging techniques provided additional information on the presumed age, gender and possible illnesses of the individuals. “All these results, coupled with a careful analysis of historical documents, pointed to a possible mix-up of the two skeletons,” explains Doll.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Analysis of the so-called mitochondrial DNA confirmed this suspicion. This genetic information is only passed on to descendants via the maternal line and is suitable for determining parentage. Comparison with a living descendant of Schinderhannes in the fifth generation indicated that the skeleton attributed to Black Jonas could have originated from Schinderhannes.

The last step in solving the mystery was to analyze the DNA from the nuclei of the skeletal bones. A new molecular genetic method makes it possible to examine almost 5,000 so-called markers. These unequivocally confirmed the family relationship over five generations.

The researchers have not yet uncovered the whereabouts of Schwarzer Jonas and who is behind the now “orphaned skeleton.” “So it remains exciting,” says Doll.

The real skeleton of Schinderhannes has been removed from the exhibition for conservation reasons. However, visitors can see an artist’s replica of the skeleton and a model of the brigand himself in the Anatomical Collection.

More information:

Walther Parson et al, Remains of the German outlaw Johannes Bückler alias Schinderhannes identified by an interdisciplinary approach, Forensic Science International: Genetics (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2025.103276

Provided by

Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg

Citation:

Historical robber ‘Schinderhannes’ clearly identified: Skeletons were mixed up about 220 years ago (2025, March 24)