Building a space station on the Moon might seem like something out of a science fiction movie, but each new lunar mission is bringing that idea closer to reality. Scientists are homing in on potential lunar ice reservoirs in permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs. These are key to setting up any sort of sustainable lunar infrastructure.

In late August 2023, India’s Chandrayaan-3 lander touched down on the lunar surface in the south polar region, which scientists suspect may harbor ice. This landing marked a significant milestone not only for India but for the scientific community at large.

For planetary scientists like me, measurements from instruments onboard Chandrayaan-3’s Vikram lander and its small, six-wheeled rover Pragyan provide a tantalizing up-close glimpse of the parts of the Moon most likely to contain ice. Earlier observations have shown ice is present in some permanently shadowed regions, but estimates vary widely regarding the amount, form and distribution of these ice deposits.

Polar ice deposits

My team at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics has a goal of understanding where water on the Moon came from. Comets or asteroids crashing into the Moon are options, as are volcanic activity and solar wind.

Each of these events leaves behind a distinctive chemical fingerprint, so if we can see those fingerprints, we might be able to trace them to the source of water. For example, sulfur is expected in higher amounts in lunar ice deposits if volcanic activity rather than comets created the ice.

Like water, sulfur is a “volatile” element on the Moon, because on the lunar surface it’s not very stable. It’s easily vaporized and lost to space. Given its temperamental nature, sulfur is expected to accumulate only in the colder parts of the Moon.

While the Vikram lander didn’t land in a permanently shadowed region, it measured the temperature at a high southern latitude of 69.37°S and was able to identify sulfur in soil grains on the lunar surface. The sulfur measurement is intriguing because sulfur may point toward the source of the Moon’s water.

So, scientists can use temperature as a way of finding where volatiles like these may end up. Temperature measurements from Chandrayaan-3 could allow scientists to test models of volatile stability and figure out how recently the sulfur may have accumulated at the landing site.

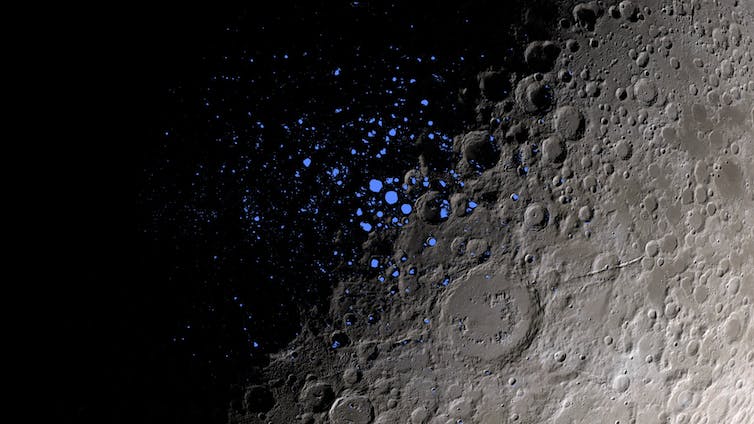

Some dark craters on the Moon, indicated here in blue, never get light. Scientists think some of these permanently shadowed regions could contain ice.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Tools for discovery

Vikram and Pragyan are the newest in a series of spacecraft that have helped scientists study water on the Moon. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter launched in 2009 and has spent the past several years observing the Moon from orbit. I’m a co-investigator on LRO, and I use its data to study the distribution, form and abundance of…