Ransomware gangs that steal a company’s data and then get paid a ransom fee to delete it don’t always follow through on their promise.

The number of cases where something like this has happened has increased, according to a report published by Coveware this week and according to several incidents shared by security researchers with ZDNet researchers over the past few months.

These incidents take place only for a certain category of ransomware attacks — namely those carried out by “big-game hunters” or “human-operated” ransomware gangs.

These two terms refer to incidents where a ransomware gang specifically targets enterprise or government networks, knowing that once infected, these victims can’t afford prolonged downtimes and will likely agree to huge payouts.

But since the fall of 2019, more and more ransomware gangs began stealing large troves of files from the hacked organizations before encrypting the victims’ files.

The idea was to threaten the victim to release its sensitive files online if the company wanted to restore its network from backups instead of paying for a decryption key to recover its files.

Some ransomware gangs even created dedicated portals called “leak sites,” where they’d publish data from companies that didn’t want to pay.

If hacked companies agreed to pay for a decryption key, ransomware gangs also promised to delete the data they had stolen.

In a report published this week, Coveware, a company that provides incident response services to hacked companies, said that half of the ransomware incidents it investigated in Q3 2020 had involved the theft of company data before files were encrypted, doubling the number of ransomware incidents preceded by data theft it saw in the previous quarter.

But Coveware says that these types of attacks have reached a “tipping point” and that more and more incidents are being reported where ransomware gangs aren’t keeping their promises.

For example, Coveware said it had seen groups using the REvil (Sodinokibi) ransomware approach victims weeks after the victim paid a ransom demand and ask for a second payment using renewed threats to make public the same data that victims thought was deleted weeks before.

Coveware said it also saw the Netwalker (Mailto) and Mespinoza (Pysa) gangs publish stolen data on their leak sites even if the victim companies had paid the ransom demand. Security researchers have told ZDNet that these incidents were most likely caused by technical errors in the ransomware gang’s platforms, but this still meant that the ransomware gangs hadn’t deleted the data as they promised.

Further, Coveware also said it observed the Conti ransomware gang send victims falsified evidence as proof of having deleted the data. Such evidence is usually requested by the victim’s legal team, but sending over falsified proof means the ransomware gang never intended to delete the data and was most likely intent on reusing at a later point.

On top of this, Coveware said it also saw the Maze ransomware gang post stolen data on their leak sites accidentally, even before they notified victims that they had stolen their files.

This has also happened with the Sekhmet and Egregor gangs; both considered to have spun off from the original Maze operation, Coveware said.

In addition to these, ZDNet also learned of additional incidents from other companies providing incident response services for ransomware attacks.

Most of these incidents involve the Maze gang, the pioneer of the ransomware leak site, and the double-extortion scheme. More exactly, they involve “affiliates,” a term that describes cybercriminals who bought access to the Maze ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) platform and were using the Maze ransomware to encrypt files.

But while some affiliates play by the rules, some haven’t. There have been cases where a former Maze affiliate who was kicked out of the Maze RaaS program had approached and tried to extort former victims with the same stolen data for the second time, data which they promised to delete.

There have also been cases where Maze affiliates accidentally posted stolen data on the Maze leak site, even after a successful ransom payment. The data was eventually taken down, but not after the posts on the Maze site got hundreds or thousands of reads (and potential downloads).

Things got worse throughout the year for Maze affiliates as antivirus companies started detecting Maze payloads and blocking the encryption and stopping attacks.

In many of these cases, the Maze affiliates had to settle for using only the data they managed to steal before the encryption was blocked and often had to settle for smaller ransom payments.

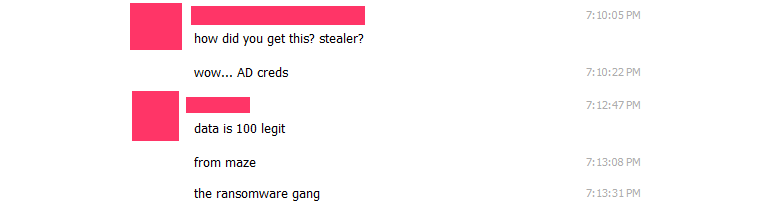

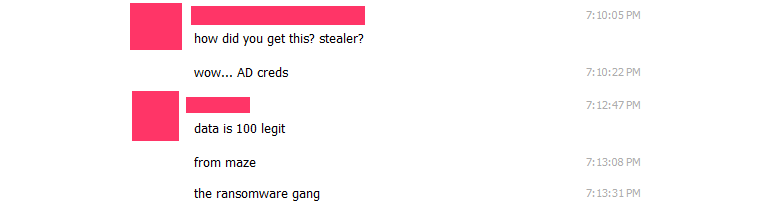

Seeking new avenues of profits, in at least two cases, a Maze group attempted to sell employee credentials and personal data to security researchers posing as underground data brokers.

These examples confirm what many security researchers had already suspected — namely, that ransomware gangs can’t be trusted or taken on their word.

“Unlike negotiating for a decryption key, negotiating for the suppression of stolen data has no finite end,” Coveware wrote in its report. “Once a victim receives a decryption key, it can’t be taken away and does not degrade with time. With stolen data, a threat actor can return for a second payment at any point in the future.”

The security firm is now recommending that companies never consider that any of their data to be deleted and plan accordingly, which usually involves notifying all impacted users and employees.

The advice needs to be given because some companies have been using the excuse that they’ve paid the ransom demand and that the ransomware gang made a pinky-promise to delete the data as an excuse not to notify their users and employees.

Since many of the documents stolen in ransomware attacks contain sensitive personal and financial details, if resold, these documents can be very useful for a slew of fraudulent operations that a victim company’s customers or employees need to be aware of and prepare for.