Neanderthals may have lost out to Homo sapiens in the evolutionary battle for survival, but as time goes on we’re learning about more and more similarities between the species – and according to new research, that extends to the raising of children.

A new study used geochemical and histological techniques to look at three Neanderthal milk teeth, finding that these kids started on solid food at the age of about 5 or 6 months… just like modern-day humans in fact.

Teeth have growth lines that are similar to the rings inside a tree trunk, marking shifts in development and diet that the scientists have been able to identify. It helps to remove some of the mystery around how Neanderthal children were born and raised.

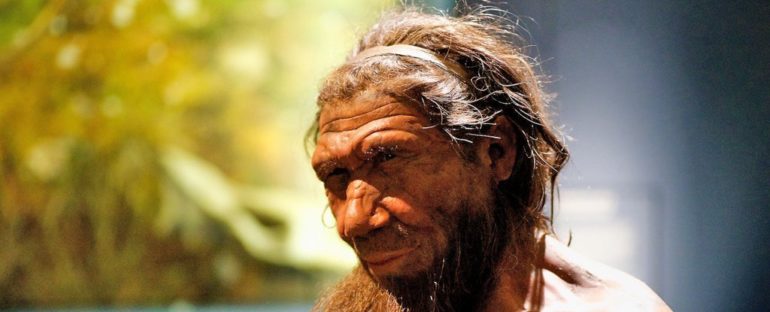

(Stefano Benazzi)

“Now, we know that also Neanderthals started to wean their children when modern humans do,” says anthropologist Alessia Nava, from the University of Kent in the UK.

“The beginning of weaning relates to physiology rather than to cultural factors. In modern humans, in fact, the first introduction of solid food occurs at around 6 months of age when the child needs a more energetic food supply, and it is shared by very different cultures and societies.”

The teeth were originally recovered from northeastern Italy and have been dated as being between 45,000 and 70,000 years old. Paper-thin slices of tooth were cut off, analysed, and then reconstructed.

Included in the study was an analysis of strontium isotopes in the teeth enamel. Comparing the chemical composition with contemporary rodent and human teeth revealed that Neanderthals perhaps stayed closer to home than has been previously thought.

As with humans, it appears that it was the growing brain and its demands for extra fuel that promoted Neanderthal weaning. If that’s correct, then it means experts can infer more details about our evolutionary cousins.

“This work’s results imply similar energy demands during early infancy and a close pace of growth between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals,” says anthropologist Stefano Benazzi, from the University of Bologna in Italy.

“Taken together, these factors possibly suggest that Neanderthal newborns were of similar weight to modern human neonates, pointing to a likely similar gestational history and early-life ontogeny, and potentially shorter inter-birth interval.”

One of the hypotheses put forward for the eventual demise of the Neanderthals is that a long period of breastfeeding reduced fertility rates, ultimately allowing Homo sapiens to outnumber them. That idea isn’t supported by this new study, the researchers say.

Exactly why modern-day human beings survived and Neanderthals didn’t continues to intrigue scientists, and there remain a lot of questions about how these ancient people lived and died – some of which this new research can help answer.

Milk teeth begin to be formed in the womb, and so tooth analysis can also tell us something about the diets and lives of mothers as well as children – but that will have to be a topic for future research, the study authors say.

The research has been published in PNAS.