If you live on the East Coast, you may have driven through roundabouts in your neighborhood countless times. Or maybe, if you’re in some parts farther west, you’ve never encountered one of these intersections. But roundabouts, while a relatively new traffic control measure, are catching on across the United States.

Roundabouts, also known as traffic circles or rotaries, are circular intersections designed to improve traffic flow and safety. They offer several advantages over conventional intersections controlled by traffic signals or stop signs, but by far the most important one is safety.

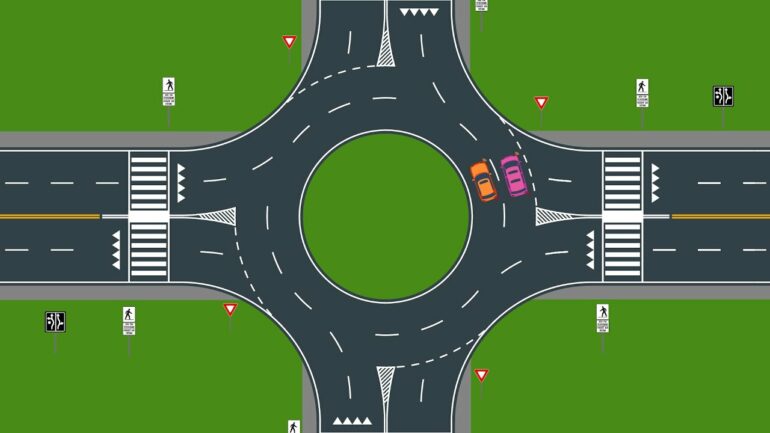

Modern roundabouts can have one or two lanes, and usually have four exit options.

AP Photo/Alex Slitz

I research transportation engineering, particularly traffic safety and traffic operations. Some of my past studies have examined the safety and operational effects of installing roundabouts at an intersection. I’ve also compared the performance of roundabouts versus stop-controlled intersections.

A brief history of roundabouts

As early as the 1700s, some city planners proposed and even constructed circular places, sites where roads converged, like the Circus in Bath, England, and the Place Charles de Gaulle in France. In the U.S., architect Pierre L’Enfant built several into his design for Washington, D.C.. These circles were the predecessors to roundabouts.

In 1903, French architect and influential urban planner Eugène Hénard was one of the first people who introduced the idea of moving traffic in a circle to control busy intersections in Paris.

Around the same time, William Phelps Eno, an American businessman known as the father of traffic safety and control, also proposed roundabouts to alleviate traffic congestion in New York City.

In the years that followed, a few other cities tried out a roundabout-like design, with varying levels of success. These roundabouts didn’t have any sort of standardized design guidelines, and most of them were too large to be effective and efficient, as vehicles would enter at higher speeds without always yielding.

The birth of the modern roundabout came with yield-at-entry regulations, adopted in some towns in Great Britain in the 1950s. With yield-at-entry regulations, the vehicles entering the roundabout had to give way to vehicles already circulating in the roundabout. This was made a rule nationwide in the United Kingdom in 1966, then in France in 1983.

Yield-at-entry meant vehicles drove through these modern roundabouts more slowly, and over the years, engineers began adding more features that made them look closer to how roundabouts do now. Many added pedestrian crossings and splitter islands – or raised curbs where vehicles entered and exited – which controlled the vehicles’ speeds.

Engineers, planners and decision-makers worldwide noticed that these roundabouts improved traffic flow, reduced congestion and improved safety at intersections….