How fast does a droplet flow along a fiber? It depends on the diameter of the fiber, and also on its substructure. These are the findings of a study conducted by researchers from the University of Liège who are interested in microfluidics, especially water harvesting in arid/semi-arid regions of our planet. These results are published in Physical Review Fluids.

Similar to moisture farms imagined in science-fiction worlds like that of “Star Wars,” many plant species from arid or semi-arid regions of Earth have developed ingenious strategies to capture water from the air to ensure their survival. Recently, researchers have focused on understanding the fundamental mechanisms of water transport, intending to reproduce and improve them, especially for facilitating the collection of atmospheric moisture in deserts.

A recent study led by the GRASP (Group of Research and Applications in Statistical Physics) at the University of Liège sought to grasp better the factors influencing these precious droplets’ movement. To do this, scientists have tracked in real-time the characteristics and dynamics of these droplets as they slid along individual fibers or bundles of fibers.

“Following a droplet as it descends along a vertical fiber under the influence of gravity presents a complex experimental challenge: how to track a droplet over several meters of thread?” explains Matteo Léonard, a researcher at GRASP and the study’s lead author. To address this problem, researchers devised a clever device in their laboratory. “Instead of following the fall of a droplet, we set the fiber in motion so that its speed is exactly equal and opposite to that of the droplet. This way, the droplet remains ‘stationary’ in front of the camera.”

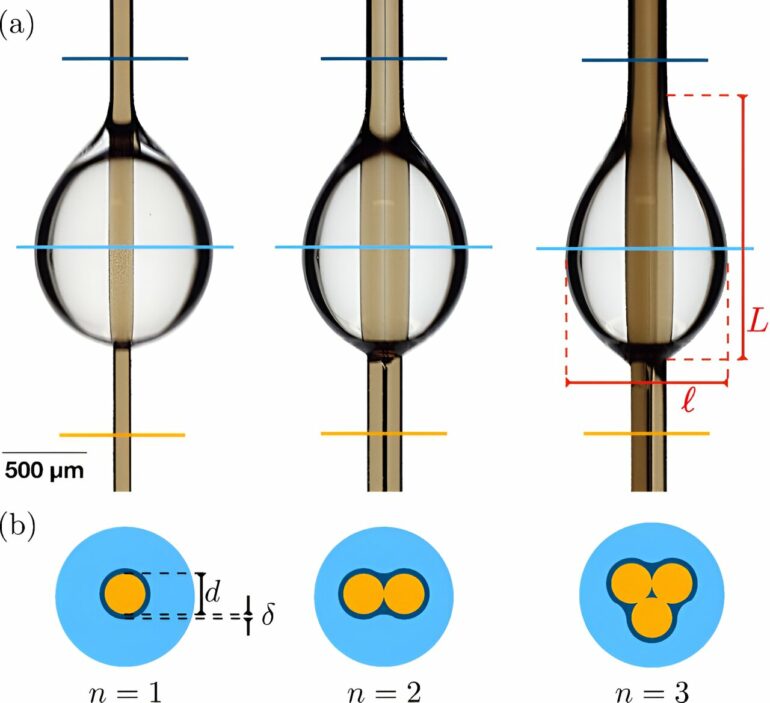

With this challenge overcome, the researchers first used fibers of different diameters. They observed that droplets had a lower speed at a given volume when the fibers were thicker, as predicted by theory. Subsequently, researchers created bundles of fibers by tying the ends of two or more fibers together and applying slight torsion to ensure contact between all the fibers.

“This configuration created a bundle of fibers with grooves, similar to the braiding of strands in a rope, which resulted in grooves appearing on the cord,” explains Leonard. In this configuration, researchers observed the same behaviors as with single fibers: as the number of fibers in the bundle increased, the overall diameter of the bundle increased, resulting in lower speed at a given volume. This predictable behavior, however, concealed a more complex phenomenon.

Indeed, what about the behavior of the droplet in the case where both configurations (single and bundle) have the same diameter (i.e., a fiber with a diameter of 0.28mm versus two fibers with a diameter of 0.14mm)? Since the hindrance of the phenomenon is dissipation (i.e., friction within the liquid and between the liquid and the fiber), one might expect that both cases would yield identical results because the contact surface between the liquid and the fiber is the same in both cases.

“Not at all. We observed that the droplet on the bundle of fibers was faster over the same distance traveled. It also lost the most volume,” says Leonard. Researchers believe that in this configuration, the droplet loses volume because it tends to “fill” the grooves with its own volume, thereby creating a liquid rail on which it slides more efficiently and thus faster.

The results of this study make a significant contribution to the field of designing structures for atmospheric water collection. Notably, it can potentially improve the efficiency of cloud nets, which consist of a network of fibers, at a low cost. Furthermore, this research highlights the growing importance of substructures regularly observed in organisms living in desert environments. These substructures, such as micro-grooves or micro-hairs, demonstrate nature’s ingenuity in capturing and transporting water, inspiring future technological innovations.

More information:

M. Leonard et al, Droplets sliding on single and multiple vertical fibers, Physical Review Fluids (2023). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.8.103601

Provided by

University de Liege

Citation:

Studying the mechanisms of water transport along a fiber (2023, October 27)