You’re probably familiar with classic sauropod dinosaurs – the four-legged herbivores famous for their long necks and tails. Animals such as Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus and Diplodocus have been standard fixtures in science museums since the 1800s.

With their small brains and enormous bodies, these creatures have long been the poster children for animals destined to go extinct. But recent discoveries have completely rewritten the doomed sauropod narrative.

I study a lesser known group of sauropod dinosaurs – the Titanosauria, or “titanic reptiles.” Instead of going extinct, titanosaurs flourished long after their more famous cousins vanished. Not only were they large and in charge on all seven continents, they held their own amid the newly evolved duck-billed and horned dinosaurs, until an asteroid struck Earth and ended the age of dinosaurs.

The secret to titanosaurs’ remarkable biological success may be how they merged the best of both reptile and mammal characteristics to form a unique way of life.

Moving with the continents

Titanosaurs originated by the Early Cretaceous Period, nearly 126 million years ago, at a time when many of the Earth’s landmasses were much closer together than they are today.

Starting about 200 million years ago, the supercontinent Pangea began to break apart and drift.

Over the next 75 million to 80 million years, the continents slowly separated, and titanosaurs drifted along with the changing formations, becoming distributed worldwide.

There were nearly 100 species of titanosaurs, making up more than 30% of known sauropod dinosaurs. They varied greatly in size. From the largest known sauropods ever discovered, including Argentinosaurus, Patagotitan and Futalognkosaurus, whose weight exceeded 60 tons (54.4 metric tons) and were bigger than a semitruck, to the smallest known sauropods, including Rinconsaurus, Saltasaurus and Magyarosaurus, which were around only 6 tons (5.4 metric tons) and about the size of an African elephant.

Babies to titans

Like many reptiles, titanosaurs began life comparatively tiny, hatching from eggs no bigger than grapefruits.

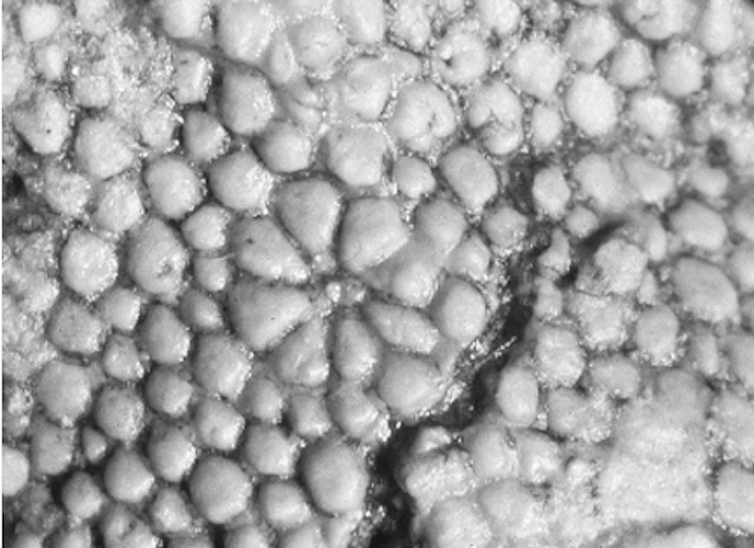

The best data on titanosaur nests and eggs comes from a site in Argentina called Auca Mahuevo, featuring 75 million-year-old exposed rocks. The site contains hundreds of fossilized nests containing thousands of eggs, some of which are so well preserved, scientists recovered skin impressions from ancient embryos.

The fossilized skin of a titanosaur embryo discovered in Argentina.

Courtesy of L. M. Chiappe, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, CC BY-ND

The sheer number of nests found together, in multiple geological layers, suggests titanosaurs returned to this site repeatedly to lay their eggs. The nests are so closely spaced, it’s unlikely an adult titanosaur would have been able to move freely through the nesting…