The 2020s have already seen many lunar landing attempts, although several of them have crashed or toppled over. With all the excitement surrounding the prospect of humans returning to the Moon, both commercial interests and scientists stand to gain.

The Moon is uniquely suitable for researchers to build telescopes they can’t put on Earth because it doesn’t have as much satellite interference as Earth, nor a magnetic field blocking out radio waves. But only recently have astronomers like me started thinking about potential conflicts between the desire to expand knowledge of the universe on one side and geopolitical rivalries and commercial gain on the other, and how to balance those interests.

As an astronomer and the co-chair of the International Astronomical Union’s working group Astronomy from the Moon, I’m on the hook to investigate this question.

Everyone to the south pole

By 2035 – just 10 or so years away – American and Chinese rockets could be carrying humans to long-term lunar bases.

Both bases are planned for the same small areas near the south pole because of the near-constant solar power available in this region and the rich source of water that scientists believe could be found in the Moon’s darkest regions nearby.

Unlike the Earth, the Moon is not tilted relative to its path around the Sun. As a result, the Sun circles the horizon near the poles, almost never setting on some crater rims. There, the never-setting Sun casts long shadows over nearby craters, hiding their floors from direct sunlight for the past 4 billion years, 90% of the age of the solar system.

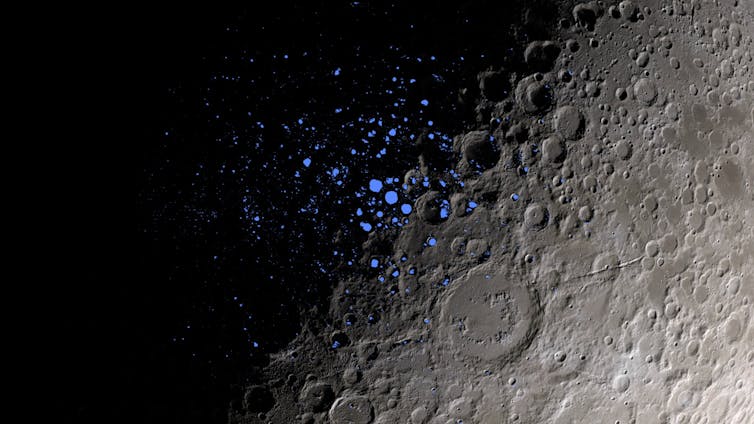

These craters are basically pits of eternal darkness. And it’s not just dark down there, it’s also cold: below -418 degrees Fahrenheit (-250 degrees Celsius). It’s so cold that scientists predict that water in the form of ice at the bottom of these craters – likely brought by ancient asteroids colliding with the Moon’s surface – will not melt or evaporate away for a very long time.

Dark craters on the Moon, parts of which are indicated here in blue, never get sunlight. Scientists think some of these permanently shadowed regions could contain water ice.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Surveys from lunar orbit suggest that these craters, called permanently shadowed regions, could hold half a billion tons of water.

The constant sunlight for solar power and proximity to frozen water makes the Moon’s poles attractive for human bases. The bases will also need water to drink, wash up and grow crops to feed hungry astronauts. It is hopelessly expensive to bring long-term water supplies from Earth, so a local watering hole is a big deal.

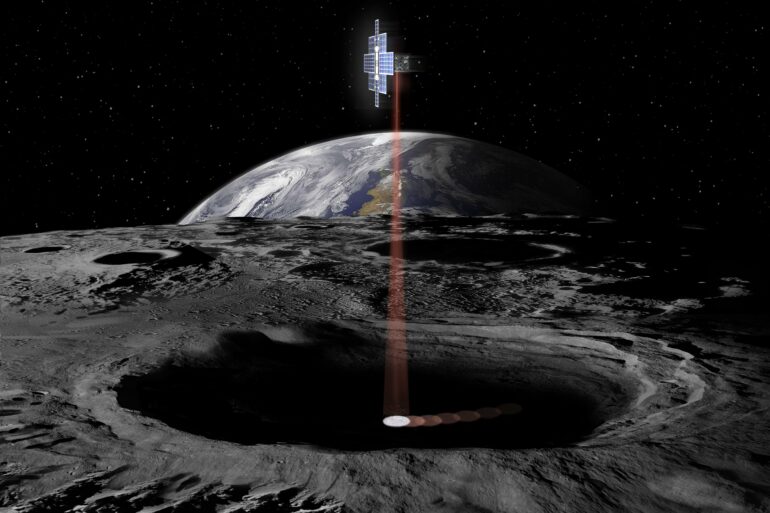

Telescopes on the Moon

For decades, astronomers had ignored the Moon as a potential site for telescopes because it was simply infeasible to build them there. But human bases open up new opportunities.

The radio-sheltered far side of the Moon, the part we never…