A diverse group of lizards known as the social skinks is helping scientists answer questions about some of the fundamental workings of evolution.

Skinks are a large group of lizards that typically follow a similar body plan.

But one group, known as the social skinks in the tribe Tiliquini, show a wide variety of forms from big-bodied, short-legged species to long-tailed and long-legged animals. These wildly divergent skinks are giving biologists the chance to study the very basics of evolution.

They have all evolved within the last 20 million years, allowing researchers to track how the different species developed different traits.

Dr. Ian Brennan is a researcher at the Natural History Museum who studies reptiles. He was part of the team that built a new family tree for these skinks and then used it to answer questions about their evolution.

“This group in particular has got really weird,” explains Brennan. “And this amount of morphological variation in a relatively short period of time is pretty interesting.”

“Our first goal was to build an evolutionary tree for the group to understand their relationships and to appreciate how these species are related to one another. Once we had the tree, our second goal was to look at how they got from being a standard skink form, which is what they look like at the base of the tree, to these really derived and really modified forms that are embedded deep in the tree.”

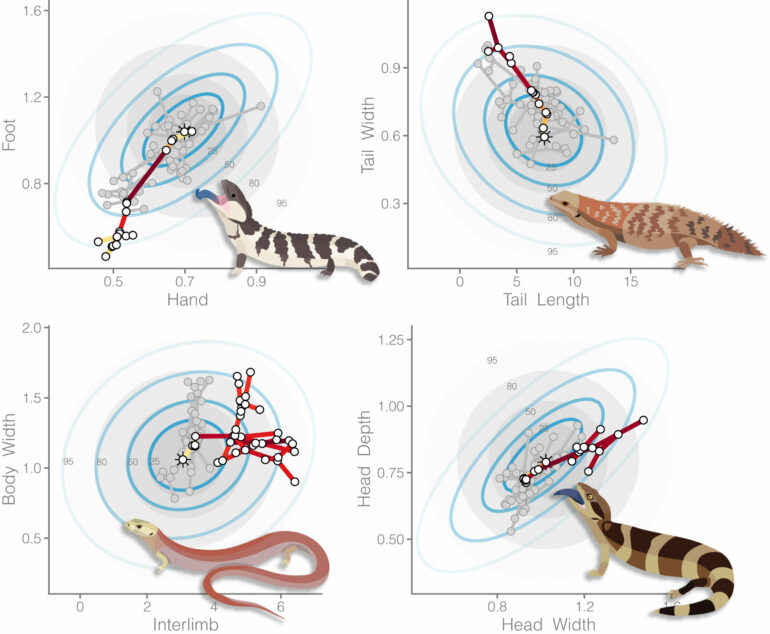

They found that the lizards seem to have gone through periods of relatively slow, steady evolution, punctuated by periods of rapid change. The results are published in the journal Current Biology.

Let’s talk about skinks

There are about 1,500 species of skink, spread across almost every environment apart from the polar and the subarctic regions. These include species that burrow, others which climb and some that swim.

But despite this huge geographic distribution and diversity in behaviors, by and large, most skinks look pretty similar. The basic shape is one of a smooth, tube-like body, well developed legs, and not much of a neck.

“Skinks are a group that are generally pretty morphologically conserved,” explains Brennan. “Like, when somebody who is familiar with lizards sees a skink, they go, that’s a skink!”

“You just know what they look like.”

The social skinks mix things up. Named because unusually for lizards, many of the species within this group live in highly gregarious family groups, they also push the boundaries of what skinks look like.

Some species have shrunk, evolving short tails and legs, and are covered with spines. This allows them to lodge themselves within the crevices of trees and bark. Others have developed incredible long, prehensile tails and long legs that enable scrambling through the treetops. Whereas the blue-tongued skinks have increased in size, becoming large-bodied and covering themselves in bone-embedded skin as they roam around the Australian outback.

It is this diversity of features that has allowed Brennan and his colleagues to investigate some of the foundations of evolution.

Evolutionary answers

One evolutionary theory suggests that the evolution of different traits, such as large body size or elongated limbs, happens slowly over time. This would mean that species such as the blue-tongued skinks would have developed each distinctive characteristic gradually, in a process known as Darwinian gradualism.

Another theory, called Simpsonian jump, instead argues that these features can appear abruptly. This would mean that the blue-tongued skinks evolved their characteristic short limbs and long bodies in just a short period of time.

What the researchers found was something of a mix. There were times in which evolution was gradual, but this was peppered with rapid spurts of inventiveness.

“We tested this idea using comparative methods to look at the evolution of these traits,” explains Brennan. “And we found that across most traits we see this heterogeneous pattern.”

“Evolution might be gradual for long periods of time, but then it’s punctuated by these periods where you have huge amounts of change.”

It seems likely that these rapid bursts of evolution are linked to, for example, species arriving on a new island or exploring a new lifestyle such as becoming nocturnal. And it is probable that this pattern is far more widespread within nature than has been realized.

“Where we have looked, the jump patterns are more common than we would have thought,” says Brennan. “But we just haven’t really looked at it across enough groups to be certain.”

This relatively modest group of lizards is helping the researchers answer some of the key questions about evolution, but it could also shed light on other interesting topics. As one of the few groups of reptiles in which social behavior has evolved, Brennan hopes that the new evolutionary tree could in the future inform how and why sociality evolved in reptiles.

More information:

Ian G. Brennan et al, Evolutionary bursts drive morphological novelty in the world’s largest skinks, Current Biology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.07.039

Provided by

Natural History Museum

This story is republished courtesy of Natural History Museum. Read the original story here.

Citation:

Wildly divergent skinks provide a window into how evolution works (2024, August 15)