by Anne J. Manning, Harvard Gazette

A new analysis led by a group of college researchers finds the U.S. will fall short of its recently finalized target for reducing vehicle emissions by nearly 15 percent over the next decade because of unrealistic goals for increasing electric-vehicle production. But adding more hybrids to the mix could help.

The study, published in Nature Communications, finds the U.S. won’t come close to its EV sales target by 2032, due mostly to bottlenecks in supply chains for crucial minerals like graphite and cobalt. Failing to correct these issues would amount to nearly 60 million extra tons of carbon dioxide emissions over the next eight years.

Paper co-author and economics concentrator Megan Yeo ’25 said the team sought to break down the EPA’s stringent new emissions goals and assess whether they were realistic.

“First we asked, ‘How many EVs need to be sold to reach that target?’ After that, we looked at different scenarios,” said Yeo, who co-authored the paper with Harvard Law School senior research associate Ashley Nunes, along with first author Lucas Woodley ’23 and Chung Yi See ’22.

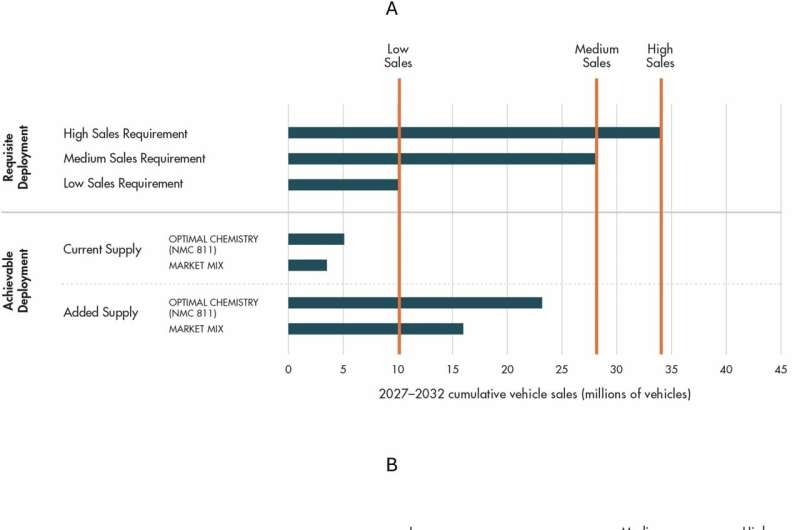

The researchers found that meeting the new standards would require replacing at least 10.21 million internal combustion engine vehicles with EVs between 2027 and 2032. But they estimated the U.S. and its allies would only be able to support the manufacture of about 5.09 million EVs during that period, falling short of the goal by about half.

Manufacturing EVs and their rechargeable batteries requires large amounts of minerals including cobalt, graphite, lithium, and nickel. The U.S. and its allies likely have ample reserves of the raw materials.

The problem is production capacity—the ability to adequately mine and refine the materials. The challenge is particularly acute for graphite, which has not been mined domestically since the mid-20th century.

Overview of EV sales scenarios and impact of mineral supply constraints. © Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51152-9

The team scoured for solutions, including rethinking emissions goals by producing more hybrid-electric vehicles. HEVs require fewer mineral resources but have reduced tailpipe emissions, offering a way to close the gap on emissions and expand the government’s focus beyond EVs.

“We suggest exploring HEVs as an alternative pathway,” Yeo said.

According to Nunes, another of the study’s takeaways is that the U.S. might be able to build enough electric cars if it leaned more heavily on China for mineral resources. But U.S. lawmakers are wary of this approach for national security reasons.

“Americans may have to ask, what do we value more—fewer emissions or energy security?” Nunes said.

Singapore native Yeo said she aspires to be a public-sector economist in her home country and that joining Nunes’ research group to work on the EV analysis opened her eyes to the rigors and constraints of evaluating public policy.

“Setting lower and upper bounds for different scenarios, and running through alternative possibilities, robustness checks, and assumptions, were all very valuable skills for me to learn,” Yeo said.

Working in the Nunes group, there’s “never a dull moment,” she continued, with multiple projects related to EVs and other transportation-sector climate goals in the works.

The paper’s other co-authors were Peter Cook and Seaver Wang of the Breakthrough Institute, Laurena Huh of MIT, and Daniel Palmer, a high school student at the Groton School who participated in Harvard’s precollege and secondary school programs.

More information:

Lucas Woodley et al, Climate impacts of critical mineral supply chain bottlenecks for electric vehicle deployment, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51152-9

Provided by

Harvard Gazette

This story is published courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, Harvard University’s official newspaper. For additional university news, visit Harvard.edu.

Citation:

Analysis finds flaw in US plan to cut vehicle emissions—and possible solution (2024, September 20)