Countries like Malaysia import many metric tons of plastic waste from Europe each year, paying a few pennies per kilo. This might seem strange, but according to Kai Li, it makes sense.

“As a resident of the Netherlands, you pay waste collection fees to dispose of your plastic waste. That money is used to collect, sort, and clean the waste. As a result, a significant portion of that waste is transformed into a valuable raw material, such as polyethylene pellets made from certain bottle and can packaging.”

Li studied Management Science and Engineering in China and is now researching the environmental effects of the global trade in plastic waste at the Department of Industrial Ecology at the Leiden Institute of Environmental Sciences.

Does this trade promote a circular economy, or does it ultimately lead to more pollution? Li, now in the fourth year of his Ph.D., and his colleagues have taken an interesting step toward answering this question. Their research is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Researchers had previously assumed that countries importing plastic recycled the same low proportion as the plastic waste generated domestically. Unrecycled waste is either incinerated or dumped in landfills.

This is bad news for the environment, as incineration releases toxic substances, and much plastic from landfills eventually blows into the sea. Li and his colleagues found it hard to believe that Turkey recycles only 12% of the plastic waste it imports.

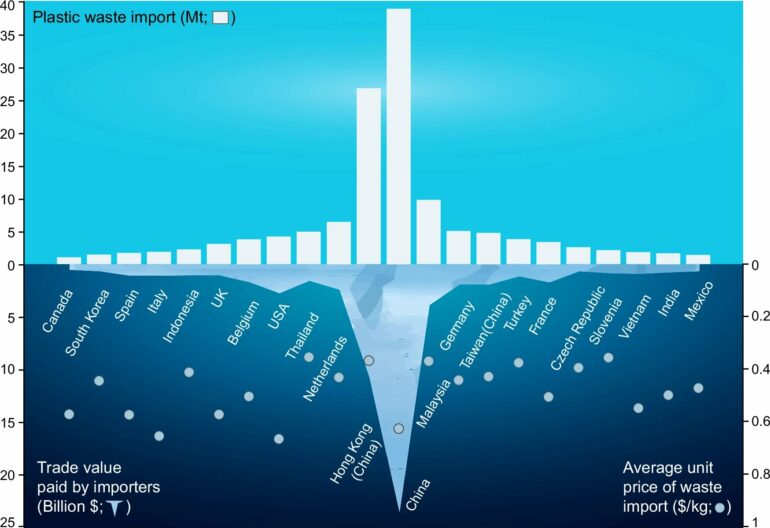

Using Comtrade, a global platform for trade data, Li was able to find out how much plastic 22 countries import and what they pay for it. “Poorer countries import the most waste, but also countries like the Netherlands and Germany do so.” Wealthy nations primarily import high-quality, well-sorted waste to keep their advanced recycling facilities operational.

Once the researchers knew how much plastic each country imported and how much they paid, they wanted to determine the cost of recycling that plastic into a resalable product. They calculated as precisely as possible what it costs to recycle each type of plastic in each country.

Li explains, “Depending on factors such as the methods used, energy costs, and labor wages, these costs vary significantly from country to country and by type of plastic.”

Li and his colleagues calculated the minimum proportion of imported plastic that needed to be recycled and sold for each country to break even and make the import profitable. “This Required Recycling Rate varies greatly by country,” Li noted. “For Turkey, it is about 50%, while for the Netherlands it approaches 80%.”

On average, a country must recycle at least 63% of imported plastic. This Required Recycling Rate is much higher than the 23% that these countries were previously thought to recycle.

The researchers assume that these minimum recycling rates are indeed being met; otherwise, it wouldn’t be profitable to pay for the raw material. Is this research result good news? Li isn’t so sure.

“It’s encouraging that more is being recycled than we thought. However, a lot of plastic waste can still be incinerated or landfilled, polluting the environment in that way.” He is now trying to ascertain how much this actually is.

Li’s supervisor, Hauke Ward, added, “If there were a price tag on environmental pollution in developing countries, those countries would recycle much more.”

Li and his colleagues examined trade flows from 2013 to 2022. In the middle of this period, something occurred that significantly changed the trade in plastic waste. “That was China’s plastic ban,” Li explained.

“Until 2018, the majority of plastic waste went there. However, it was mostly dirty and unsorted waste, which was difficult to recycle. It yielded China very little money but caused significant environmental damage. Therefore, in 2018, China banned all imports of plastic, as well as paper and other solid waste.”

The trade then shifted to Turkey and Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia and Vietnam. However, alongside this shift, there was also an improvement. International agreements, such as the amendments to the Basel Convention in 2021, now require better cleaning and sorting of waste before it can be exported.

Li says, “Due to this strict policy, we can expect the trade in plastic waste between Northern countries to increase, while that between Northern and Southern countries decreases.” This means fewer travel miles for our plastic waste.

The research findings, of course, do not change the mountain of plastic waste. Li stated, “The most important thing is that we globally work to reduce plastic waste. If governments limited plastic production, there would also be less waste.”

More information:

Kai Li et al, Economic viability requires higher recycling rates for imported plastic waste than expected, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51923-4

Citation:

Poor countries recycle far more imported plastic than previously thought—but it’s not enough (2024, October 2)