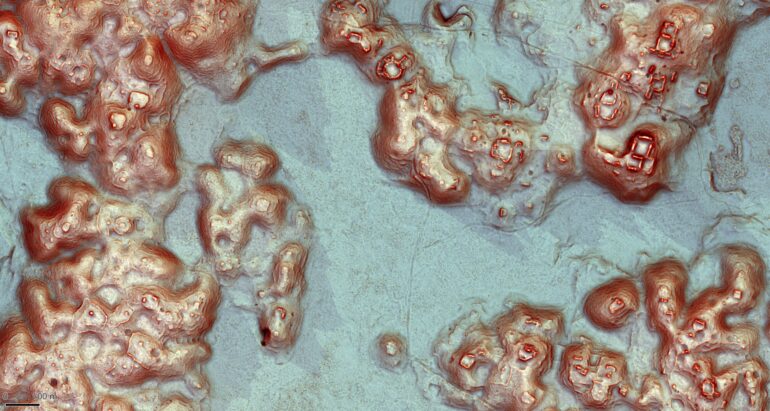

Archaeologists have analyzed lidar data from a completely unstudied corner of the Maya world in Campeche, Mexico, revealing 6,674 undiscovered Maya structures, including pyramids like those at the famous sites of Chichén Itzá or Tikal.

“For the longest time, our sample of the Maya civilization was a couple of hundred square kilometers total,” says lead author Luke Auld-Thomas from Northern Arizona University. “That sample was hard won by archaeologists who painstakingly walked over every square meter, hacking away at the vegetation with machetes, to see if they were standing on a pile of rocks that might have been someone’s home 1,500 years ago.”

In the modern day, however, lidar technology allows scientists to scan large swaths of land from the comfort of an office, uncovering anomalies in the landscape that often prove to be pyramids, family houses and other Maya infrastructure.

There is a downside, though. Lidar survey is expensive, and granting organizations don’t want to sink money into studying areas that are totally unknown and potentially devoid of Maya history. That’s why one part of Campeche was still a blank spot on archaeologists’ maps—until Auld-Thomas got an idea.

“Scientists in ecology, forestry and civil engineering have been using lidar surveys to study some of these areas for totally separate purposes,” says Auld-Thomas. “So what if a lidar survey of this area already existed?”

As it turns out, it did. In 2013, a consortium focused on measuring and monitoring carbon in Mexico’s forests had commissioned a very thorough lidar survey. Auld-Thomas, along with researchers at Tulane University, Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, and the University of Houston’s National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping analyzed this lidar data to explore 50 square miles of Campeche, Mexico, that had never been examined by archaeologists before. Their results are now published in the journal Antiquity.

They discovered a dense, diverse array of totally unstudied Maya settlements dotted throughout the region, including an entire city. These findings might just settle a heated archaeological debate that’s raged since the advent of lidar.

“Our analysis not only revealed a picture of a region that was dense with settlements, but it also revealed a lot of variability,” Auld-Thomas states. “We didn’t just find rural areas and smaller settlements. We also found a large city with pyramids right next to the area’s only highway, near a town where people have been actively farming among the ruins for years.

“The government never knew about it; the scientific community never knew about it. That really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that, no, we have not found everything, and yes, there’s a lot more to be discovered.”

Future research will focus on fieldwork at the newly discovered sites, and could be instrumental in solving modern problems facing urban development.

“The ancient world is full of examples of cities that are completely different than the cities we have today,” concludes Auld-Thomas. “There were cities that were sprawling agricultural patchworks and hyper-dense; there were cities that were highly egalitarian and extremely unequal.

“Given the environmental and social challenges we’re facing from rapid population growth, it can only help to study ancient cities and expand our view of what urban living can look like. Having a larger sample of the human career, a longer record of the accumulated residue of people’s lives, could give us the latitude to imagine better and more sustainable ways of being urban now and in the future.”

More information:

Luke Auld-Thomas et al, Running out of empty space: environmental lidar and the crowded ancient landscape of Campeche, Mexico, Antiquity (2024). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2024.148

Citation:

Have we found all the major Maya cities? Not even close, new research suggests (2024, October 28)