A research group led by Johannes Müller at the Institute of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology, at Kiel University, Germany, have shed light on the lives of people who lived over 5,600 years ago near Kosenivka, Ukraine.

Published on December 11, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, the researchers present the first detailed bioarchaeological analyses of human diets from this area and provide estimations on the causes of death of the individuals found at this site.

The people associated with the Neolithic Cucuteni-Trypilla culture lived across Eastern Europe from approximately 5500 to 2750 BCE. With up to 15,000 inhabitants, some of their mega-sites are among the earliest and largest city-like settlements in prehistoric Europe.

Despite the vast number of artifacts the Trypillia left behind, archaeologists have found very few human remains. Due to this absence, many facets of the lives of these ancient people are still undiscovered.

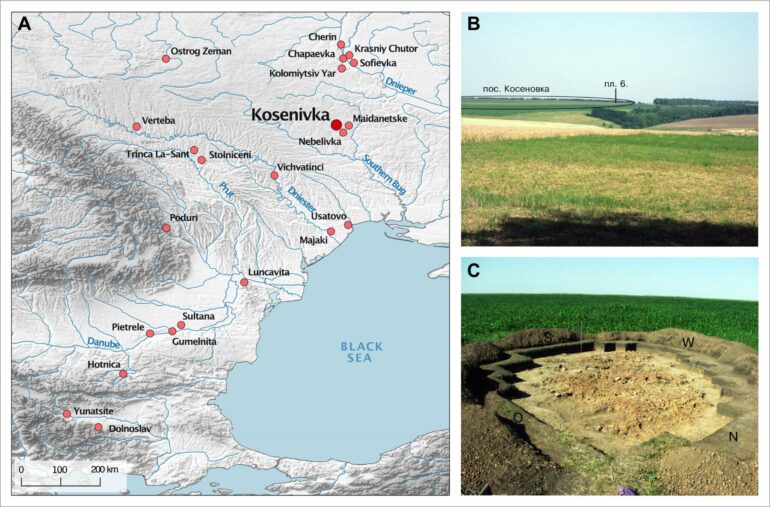

The researchers studied a settlement site near Kosenivka, Ukraine. Comprised of several houses, this site is unique for the presence of human remains.

The 50 human bone fragments recovered among the remains of a house stem from at least seven individuals—children, adults, males and a female, perhaps once inhabitants of the house. The remains of four of the individuals were also heavily burnt. The researchers were keen to explore potential causes for these burns, such as an accidental fire, or a rare form of burial rite.

The burnt bone fragments were largely found in the center of the house, and previous studies surmised the inhabitants of this site died in a house fire. Scrutinizing the pieces of bone under a microscope, the researchers concluded that the burning probably occurred quickly after death.

In the case of an accidental fire, the researchers propose that some individuals could have died of carbon monoxide poisoning, even if they fled the house.

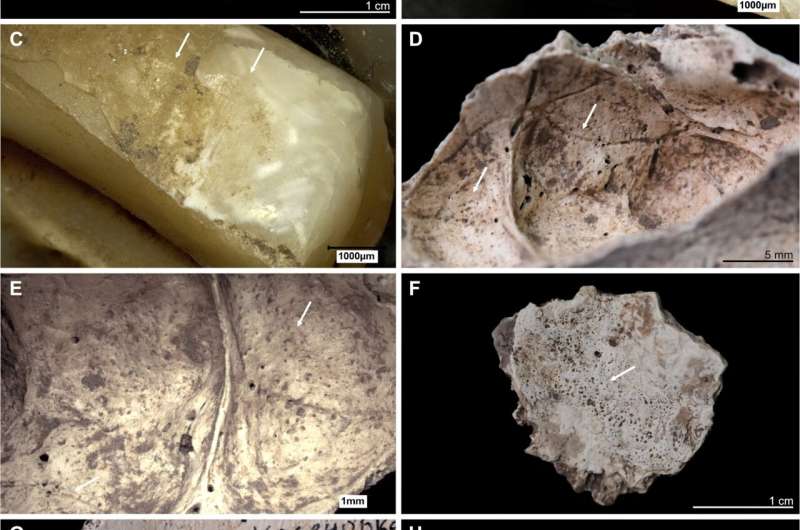

Kosenivka, selection of oral and pathological conditions. A–E: Individual 5/6/+left maxilla. A: Teeth positions 23–26 (buccal view). Signs of periodontal inflammation (upper arrows) and examples of dental calculus accumulation (third arrow) and dental chipping (lower arrow) on the first premolar (tooth 24). B: First premolar (24, mesial view). Interproximal grooving with horizonal striations on the lingual surface of the root (upper arrow) and at the cemento–enamel junction (middle arrow). Larger chipping lesion (lower arrow). C: Canine (23, distal view). Interproximal grooving, same location as on the neighboring premolar (see B), but less distinct. D, E: Signs of periosteal reaction on the left maxillary sinus (medio–superior view). Increased vessel impressions (D, upper arrow) and porosity, as well as uneven bone surface (D, lower arrow, E), indicating inflammatory processes. F: Individual 2, left temporal, fragment (endocranial view). Periosteal reaction indicated by porous new bone formation (arrow). G: Individual 5, frontal bone (endocranial view). Periosteal reaction indicated by tongue-like new bone formation and increased vessel impressions (arrows). H: Individual 5/6/+, frontal bone, right part, orbital roof (inferior view). Signs of cribra orbitalia (evidenced by porosity, see arrow). Illustration: K. Fuchs. © Fuchs et al., 2024, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

According to radiocarbon dating, one of the individuals died ca. 100 years later. The death of this person cannot be connected to the fire, but is otherwise unknown. Two other individuals with unhealed cranial injuries raise the question of whether violence could have played a role as well.

A review of Trypillian human bone finds showed the researchers that less than 1% of the dead were cremated, and even more rarely buried within a house.

While bones can help archaeologists speculate how ancient people died, these remains can also help us understand how they lived. By analyzing the carbon and nitrogen present in the bones—as well as in grains and the remains of animals found at the site—the researchers determined meat made up less than 10% of the inhabitants’ diets.

This is in line with teeth found at the site, which have wear marks that indicate chewing on grains and other plant fibers. That Trypillia diets consisted mostly of plants supports theories that cattle in these cultures were primarily used for manuring the fields and milk rather than meat production.

Katharina Fuchs, first author of the study, adds, “Skeletal remains are real biological archives. Although researching the Trypillia societies and their living conditions in the oldest city-like communities in Eastern Europe will remain challenging, our ‘Kosenvika case’ clearly shows that even small fragments of bone are of great help.

“By combining new osteological, isotopic, archaeobotanical and archaeological information, we provide an exceptional insight into the lives—and perhaps also the deaths—of these people.”

More information:

Life and death in Trypillia times: Interdisciplinary analyses of the unique human remains from the settlement of Kosenivka, Ukraine (3700–3600 BCE), PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289769

Provided by

Public Library of Science

Citation:

Stone Age insights: Life, death and fire in ancient Ukraine (2024, December 11)