There are still many unknowns about the causes leading to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) shift—a critical climate phenomenon in the Northern Hemisphere—to the east and west of Iceland. To date, some hypotheses suggest that this process known to the international scientific community might be related to the impact of greenhouse gases on the planet.

Now, a study published in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science reveals that the NAO shift may be a consequence of natural variability in the atmospheric system rather than anthropogenic effects altering global climatology. The new study is led by experts María Santolaria-Otín and Javier García-Serrano, from the Faculty of Physics and the Group of Meteorology at the University of Barcelona.

Why does the NAO move longitudinally?

The NAO was first identified in the early 20th century, although its consequences were known to the people of northern Europe much earlier. The NAO is one of the most studied climate variability phenomena in the scientific community. However, many aspects of the dynamics and processes controlling its variability, both temporally and spatially, are still unknown, and the evidence for its past and expected future trends is still being debated.

García-Serrano, professor at the UB’s Department of Applied Physics, says, “The atmosphere is a fluid system and shows a very chaotic and unpredictable behavior. The study reveals that we can rule out some factors that explain this NAO pattern, namely anthropogenic forcing—i.e., the impact of greenhouse gases—or ocean coupling. Factors that could help to understand these shifts in the NAO are, for example, the interaction of winds with orography or the land-sea contrast. However, we need more research studies to confirm these hypotheses.”

On a global scale, the effects of this NAO shift are likely to be small, although they could affect Arctic Sea ice variability and, consequently, other remote areas of the planet. According to the findings, this process would not alter anthropogenic global warming trends.

Regional scale effects would be more important, since the NAO explains about half of the climate variability in the area of the European continent and the Mediterranean. “However, its impact on future predictions and projections would mainly be to modulate climate change trends in certain periods,” says García-Serrano.

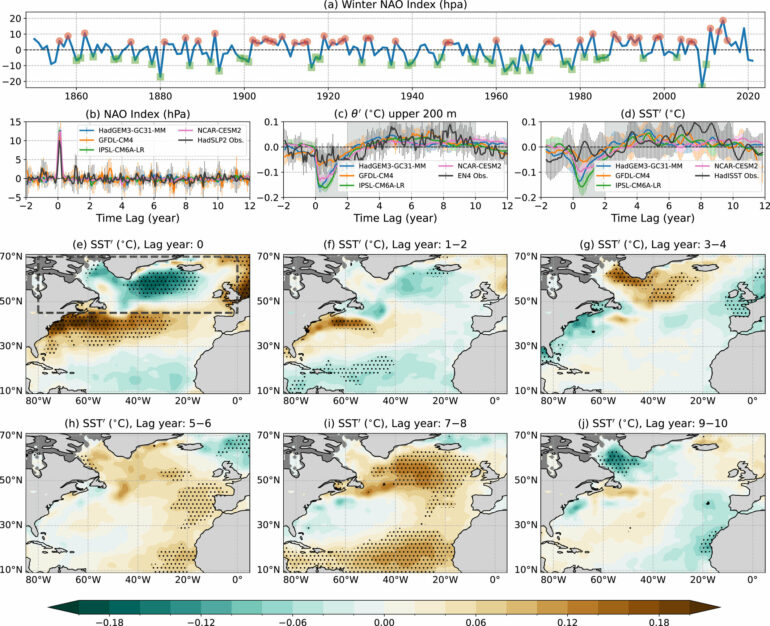

In this context, the UB team has carried out and analyzed simulations over a period of 500 years with a global climate model. Santolaria-Otín, postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study, notes, “By applying this innovative methodology, it has been possible to isolate the effects of radiative forcing and ocean coupling and thus obtain conclusions that are impossible to reach with observational data alone.”

The NAO is considered one of the most influential patterns of low-frequency variability (teleconnections) in the climate of the Northern Hemisphere. In this challenging scenario, the UB team continues to expand their studies to understand what factors control NAO shifts and their remote effects in the context of global climatology.

More information:

María Santolaria-Otín et al, Internal variability of the winter North Atlantic Oscillation longitudinal displacements, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-024-00842-8

Provided by

University of Barcelona

Citation:

500-year simulations reveal natural drivers of North Atlantic Oscillation shift (2024, December 16)