Runners wearing thick-heeled sneakers were more likely to get injured than those wearing flatter shoes, a recent study from the University of Florida has found. The paper is published in the journal Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

The study, one of the largest and most comprehensive of its kind, also found that runners with thicker heels could not accurately identify how their foot landed with each step, a likely factor in the high injury rates.Because flatter shoes are associated with less injury, the researchers say they are likely the best option for most runners to help improve sensation with the ground and learn to land in a controlled manner. But transitioning to a different shoe type or foot strike pattern can also risk injury and must be done gradually, something that lead author Heather Vincent, Ph.D., knows from personal experience.

“I had to teach myself to get out of the big, high-heeled shoes down to something with more moderate cushioning and to work on foot strengthening,” said Vincent, director of the UF Health Sports Performance Center. “It may take up to six months for it to feel natural. It’s a process.”

Both foot strike patterns and shoe type have been linked to running injuries in past studies, but the interaction between the two has been difficult to identify from small groups of runners. UF Health’s Sports Performance Center and Running Medicine Clinic sees hundreds of runners a year. That allowed the researchers to pull from more than 700 runners and six years of information on runners’ shoe type and injury history and objective data about running gait acquired with specialized treadmills and motion capture videos.

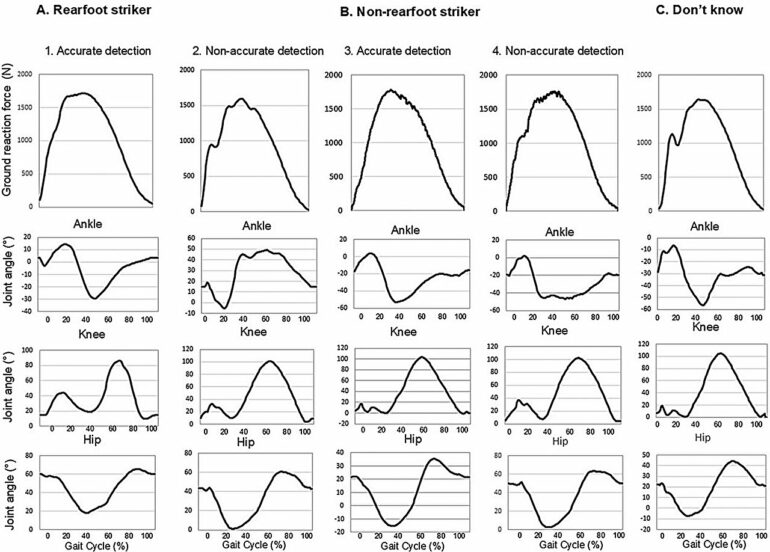

What became clear after controlling for factors like age, weight, running volume and competitiveness was that shoes with thicker heels confused runners about their gait—confusion that was strongly linked to injury.

“The shoe lies between the foot and the ground, and features like a large heel-to-toe drop make it more challenging for runners to identify how they’re striking the ground. That clouds how we retrain people or determine if someone is at risk for future injury,” Vincent said. “The runners who correctly detected mid- or fore-foot striking had very different shoes: lower heel-to-toe drop; lighter; wider toe box.”

Heather Vincent collaborated with Ryan Nixon, Ph.D., Kevin Vincent, Ph.D., and others in the UF Colleges of Medicine and Public Health and Health Professions on the study.

Although the associations between high-heeled shoes and injury were clear, it’s difficult to prove that heel-to-toe drop directly causes these injuries. Moving forward, the scientists plan to run controlled studies to see if changing shoe type affects runners’ accuracy of foot strike detection and injury rates. That would help identify the true cause of these common injuries and suggest the best fixes.

“We want to translate what we find into meaningful ways to help runners modify their form to reduce injury risk and keep them healthy for the long term,” Vincent said.

More information:

Heather K. Vincent et al, Accuracy of self-reported foot strike pattern detection among endurance runners, Frontiers in Sports and Active Living (2024). DOI: 10.3389/fspor.2024.1491486

Provided by

University of Florida

Citation:

Study reveals why these shoes could lead to more runner injuries (2024, December 18)