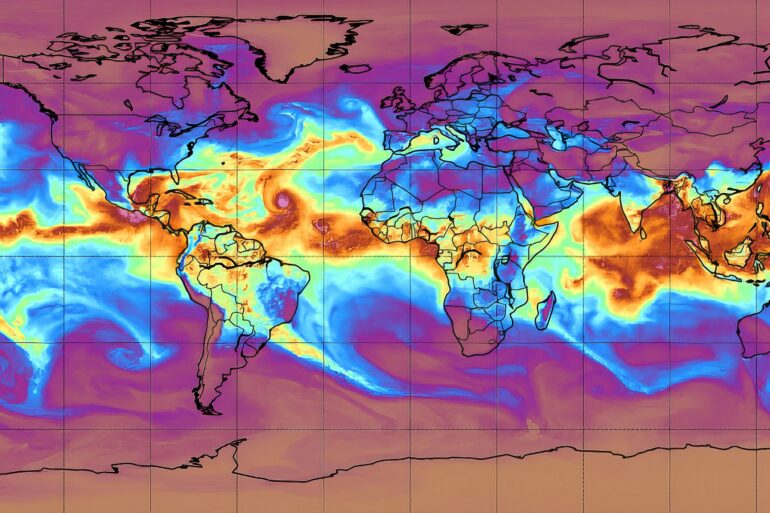

The environmental threat posed by atmospheric rivers—long, narrow ribbons of water vapor in the sky—doesn’t come only in the form of concentrated, torrential downpours and severe flooding characteristic of these natural phenomena. According to a new Yale study, they also cause extreme warm temperatures and moist heat waves.

Researchers Serena Scholz and Juan Lora say atmospheric rivers—horizontal plumes that transport water vapor from the warm subtropics to cooler areas across midlatitude and polar regions of the world—are also transporting heat. As a result, atmospheric rivers may have a greater effect on global energy movement than previously recognized.

“We’re seeing temperature anomalies associated with atmospheric rivers that are 5 to 10 degrees Celsius [9 to 18 degrees Fahrenheit] higher than the climatological mean. The numbers are astounding,” said Lora, assistant professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and co-author of a new study.

The findings are published in the journal Nature.

Scientists began using the term “atmospheric river” in the 1990s. Today, there are three to five of them winding their way through each hemisphere at any given time.

They can be thousands of miles long, but only a few hundred miles wide; the amount of water vapor they carry is about 7–15 times greater than the equivalent amount of water discharged each day by the Mississippi River. The heavy rains that often result can cause major damage and disruption, such as the Oroville Dam crisis in California in 2017 and severe floods in the UK in 2019–20.

“They’ve been defined up to this point by how much moisture they’re transporting,” said Scholz, a graduate student in Lora’s lab and the study’s lead author. “People knew there was warmth inherent in them, but they cause so much rain that moisture has been the focus.”

The new study suggests that temperature in atmospheric rivers is worth noticing, too.

Scholz and Lora analyzed 40 years of global weather data from NASA’s MERRA-2 reanalysis, as well as seven publicly available algorithms that track atmospheric rivers worldwide. Specifically, they looked at temperature increases related to atmospheric rivers on two timescales: hourly temperature spikes and heat waves of three or more days of moist heat.

“There was no doubt—atmospheric rivers are really impactful for both timescales,” Scholz said.

The researchers noted that the phenomenon has a more dramatic effect in the winter than it does in summer. This trend actually helped inspire the project in the first place; Lora had noticed that winters in Connecticut have been particularly mild and rainy in recent years, which led him and Scholz to look at heat transport in atmospheric rivers.

“And that evolved into a global study, because the numbers were so interesting,” Lora said.

Although other studies have touched upon the role that temperature plays in atmospheric rivers at higher latitudes, this is the first study to highlight mid-latitude regions, which contain several “hotspots” for atmospheric rivers. These hotspots include the east and west coasts of North America, western Europe, Australia, and southern regions of South America.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Perhaps the best-known recurring atmospheric river is the “Pineapple Express” system that brings warm moisture from the tropics, delivering rain and heavy snow to the west coasts of Canada and the U.S.

The new study shows that when atmospheric rivers occur, they change the balance of energy on the surface in several ways, the researchers say. For example, while cloudy conditions block incoming sunlight, those clouds also trap more thermal radiation near the surface, creating a transient enhanced greenhouse effect. This heating balances out the loss of sunlight—but is not the cause of temperature spikes.

Instead, the main cause of warm temperatures in atmospheric rivers is simply the transport of warm air, located near the water’s surface, from one region to another.

“As we tried to understand why this is happening, we were expecting to find a transient greenhouse-type effect going on,” Scholz said. “But it’s just heat moving from one area to another, via the river.”

More information:

Serena R. Scholz et al, Atmospheric rivers cause warm winters and extreme heat events, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08238-7

Citation:

Intense ribbons of rain also bring the heat, scientists say (2024, December 20)