As cases of dengue fever skyrocketed globally this past year, new findings by Stanford researchers and their international collaborators underscore the importance of one measure that can significantly reduce disease risk: cleaning up trash.

Dengue fever is a viral illness spread through mosquito bites. While cases can be asymptomatic, many people experience high fever and painful body aches. Second infections are often more severe and can lead to hemorrhagic fever, shock, and sometimes death. Thriving in warmer, wetter weather resulting from climate change, dengue is rapidly spreading into new locations beyond its historical tropical range. Dengue cases doubled globally between 2023–24 and spread in an “unprecedented” way to several U.S. states.

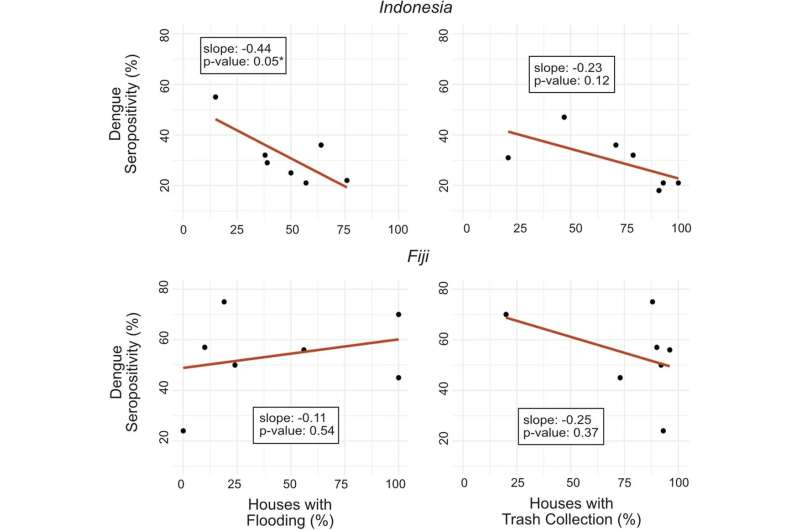

Stanford researchers and their international colleagues recently sought to better understand the transmission of dengue and two other diseases spread by the same mosquito—Zika and chikungunya—in children up to age 5 in two dengue hotspots, Fiji and Indonesia. Their study, published in BMC Infectious Diseases on Jan. 13, found that children living in households with regular garbage removal—particularly in Indonesia—had significantly lower risk of getting dengue than children whose homes had trash around them.

“Trash disposal can have a real impact on dengue risk,” said Joelle Rosser, Stanford assistant professor of medicine in the School of Medicine and the publication’s lead author. “This highlights an important area where we have an opportunity to intervene and improve the health of humans and their lived environment.”

Rosser believes that trash is an important risk factor for dengue worldwide because many types of waste can collect in shallow standing water, a favored breeding ground for the mosquito that spreads dengue, Aedes aegypti. Recent Stanford-led research has found a similar connection between trash and mosquito-borne disease risk in Kenya, while another new Stanford-led publication found that mosquitoes—and the diseases they carry—can adapt to hotter temperatures.

“We’ve seen that trash is a major dengue risk factor not only in Indonesia but also in Kenya and likely even in California,” Rosser said.

Settlement level dengue seropositivity versus flooding and trash collection rates. © BMC Infectious Diseases (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s12879-024-10315-1

High burden of disease impacts vulnerable children

The researchers studied children in 24 informal settlements in Fiji and Indonesia. They tested children up to age 5—a group especially vulnerable to the virus—for evidence of prior infection and asked detailed questions to assess environmental risk factors for these infections.

In addition to the findings about the relationship between trash removal and infection, the researchers were surprised by the magnitude of dengue infections among young children in the study. By the age of 4 to 5, 71% percent of children in Fiji and 51% of the children in Indonesia, respectively, had been infected with dengue, putting them at risk for a more severe second infection at a young age.

The findings “highlight the disproportionate burden of these diseases on children in underserved urban settlements and call for inclusive policies to ensure all communities benefit from public health interventions,” said Dr. Isra Wahid, a research investigator specializing in dengue and other mosquito-borne infectious diseases at the School of Medicine at Hasanuddin University in Indonesia and the paper’s senior author.

Study shines light on preventive measures

Wahid noted another surprising study finding: Settlements experiencing more frequent flooding had lower dengue rates, possibly due to floodwaters flushing out mosquito breeding sites. However, he added, when flooding happens in areas with poor trash collection, the remaining floodwater trapped in the containers could breed more mosquitoes and increase dengue transmission.

The findings show that environmental changes such as trash management and flood mitigation are important measures for controlling dengue and other diseases spread by the same mosquito.

“Beyond these communities, the study provides a model for addressing arbovirus transmission through environmental modifications, offering scalable solutions for other high-risk areas globally,” said Wahid. Arboviruses are diseases spread by infected mosquitoes and ticks to humans.

The research was conducted as part of the RISE (Revitalizing Informal Settlements and their Environment) project, which seeks to upgrade entire water infrastructures to build communities resilient to the impacts of climate change, including flooding and infectious disease. For the RISE intervention, Stanford researchers collaborate with local physician-scientists, ecologists, architects, engineers, and community organizers to minimize trash, enhance rainwater collection, and establish natural flood buffers.

These actions can collectively reduce mosquito breeding grounds while making communities more resilient to the increased droughts and floods expected with climate change. Both droughts and floods can worsen mosquito-borne disease, Rosser said.

Rosser will track a cohort of young children in these communities over several years. She and her colleagues will use this data to assess whether the RISE intervention impacts childhood infection rates.

Wahid hopes their new findings can help inform local government actions such as improving trash collection systems, including in informal settlements, and mitigating flood risks. Even now, the work shines a light on one meaningful way to mitigate the impacts of climate change on human health, Rosser emphasized.

“For many people, climate change is very anxiety-provoking, and it can be daunting to think how we can impact the problem if we’re not climatologists or engineers,” she said. “But there are a whole host of ways we can minimize the impacts of climate change on health and well-being—and reducing trash is one of them.”

More information:

Joelle I. Rosser et al, Seroprevalence, incidence estimates, and environmental risk factors for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika infection amongst children living in informal urban settlements in Indonesia and Fiji, BMC Infectious Diseases (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s12879-024-10315-1

Provided by

Stanford University

Citation:

As dengue cases rise, researchers point to simple solution: Trash cleanup (2025, January 13)