Flash floods like the one that swept down the Guadalupe River in Texas on July 4, 2025, can be highly unpredictable. While there are sophisticated flood prediction models and different types of warning systems in some places, effective flood protection requires extensive preparedness and awareness.

It also requires an understanding of how people receive, interpret and act on risk information and warnings. Technology can be part of the solution, but ultimately people are the critical element in any response.

As researchers who study emergency communications, we have found that simply providing people with technical information and data is often not enough to effectively communicate the danger and prompt them to act.

The human element

One of us, Keri Stephens, has led teams studying flood risk communication. They found that people who have experienced a flood are more aware of the risks. Conversely, groups that have not lived through floods typically don’t understanding various flood risks such as storm surges and flash floods. And while first responders often engage in table-top exercises and drills – very important for their readiness to respond – there are only a few examples of entire communities actively participating in warning drills.

Messages used to communicate flood risk also matter, but people need to receive them. To that end, Keri’s teams have worked with the Texas Water Development Board to develop resources that help local flood officials sort through and prioritize information about a flood hazard so they can share what is most valuable with their local communities.

The commonly used “Turn Around Don’t Drown” message, while valuable, may not resonate equally with all groups. Newly developed and tested messages such as “Keep Your Car High and Dry” appeal specifically to young adults who typically feel invincible but don’t want their prized vehicles damaged. While more research is needed, this is an example of progress in understanding an important aspect of flood communication: how recipients of the information make decisions.

Interviews conducted by researchers often include responses along these lines: “Another flash flood warning. We get these all the time. It’s never about flooding where I am.” This common refrain reveals a fundamental challenge in flood communication. When people hear “flood warning,” they often think of different things, and interpretations can vary depending on a person’s proximity to the flooding event.

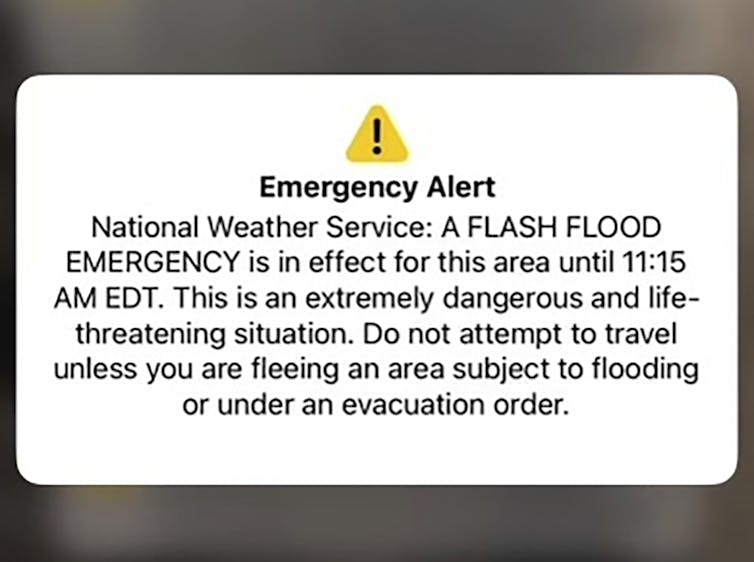

Some people equate flood warnings with streamflow gauges and sensors that monitor water levels – the technical infrastructure that triggers alerts when rivers exceed certain thresholds. Others think of mobile phone alerts, county- or geographic-specific notification systems, or even sirens.

A typical alert from the National Weather Service.

AP Photo/Lisa Rathke

Beyond technologies and digital communication, warnings…