Pick up a button mushroom from the supermarket and it squishes easily between your fingers. Snap a woody bracket mushroom off a tree trunk and you’ll struggle to break it. Both extremes grow from the same microscopic building blocks: hyphae – hair-thin tubes made mostly of the natural polymer chitin, a tough compound also found in crab shells.

As those tubes branch and weave, they form a lightweight but surprisingly strong network called mycelium. Engineers are beginning to investigate this network for use in eco-friendly materials.

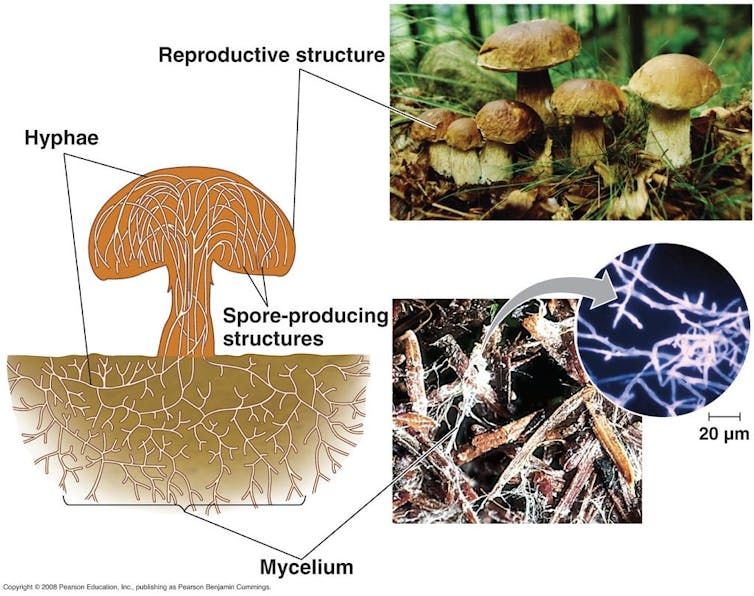

Filaments called hyphae are a mushroom’s support structures both above and below ground, and the mycelium network links multiple mushrooms together.

Milkwood.net/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Yet even within a single mushroom family, the strength of a mycelium network can vary widely. Scientists have long suspected that how the hyphae are arranged – not just what they’re made of – holds the key to understanding, and ultimately controlling, their strength. But until recently, measurements that directly link microscopic arrangement to macroscopic strength have been scarce.

I’m a mechanical engineering Ph.D. student at Binghamton University who studies bio-inspired structures. In our latest research, my colleagues and I asked a simple question: Can we tune the strength of a mushroomlike material just by changing the angle of its filaments, without adding any tougher ingredients? The answer, it turns out, is yes.

2 edible species, many tiny tests

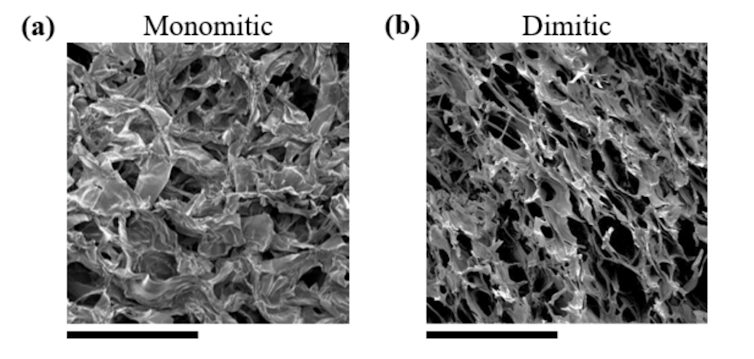

In our study, my team compared two familiar fungi. The first was the white button mushroom, whose tissue uses only thin filaments called generative filaments. The second was the maitake, also called hen-of-the-woods, whose tissue mixes in a second, thicker type of hyphae called skeletal filaments. These skeletal filaments are arranged roughly in parallel, like bundles of cables.

The two types of mushrooms used in the study: The white button mushroom is monomitic, shown on the left, meaning it has only one type of hyphae. The maitake is shown on the right, and is dimitic, meaning it has two types of hyphae.

Mohamed Khalil Elhachimi

After gently drying the caps and stems to remove any water, which can soften the material and skew the results, we zoomed in with scanning electron microscopes and tested the samples at two very different scales.

First, we tested macro-scale compression. A motor-driven piston slowly squashed each mushroom while sensors recorded how hard the sample pushed back – the same way you might squeeze a marshmallow, only with laboratory precision.

Then we pressed a diamond tip thinner than a human hair into individual filaments to measure their stiffness.

The white mushroom filaments behaved like rubber bands, averaging about 18 megapascals in stiffness – similar to natural rubber. The thicker skeletal filaments in maitake measured around 560 megapascals, more…