Outdoor lighting for buildings, roads and advertising can help people see in the dark of night, but many astronomers are growing increasingly concerned that these lights could be blinding us to the rest of the universe.

An estimate from 2023 showed that the rate of human-produced light is increasing in the night sky by as much as 10% per year.

I’m an astronomer who has chaired a standing commission on astronomical site protection for the International Astronomical Union-sponsored working groups studying ground-based light pollution.

My work with these groups has centered around the idea that lights from human activities are now affecting astronomical observatories on what used to be distant mountaintops.

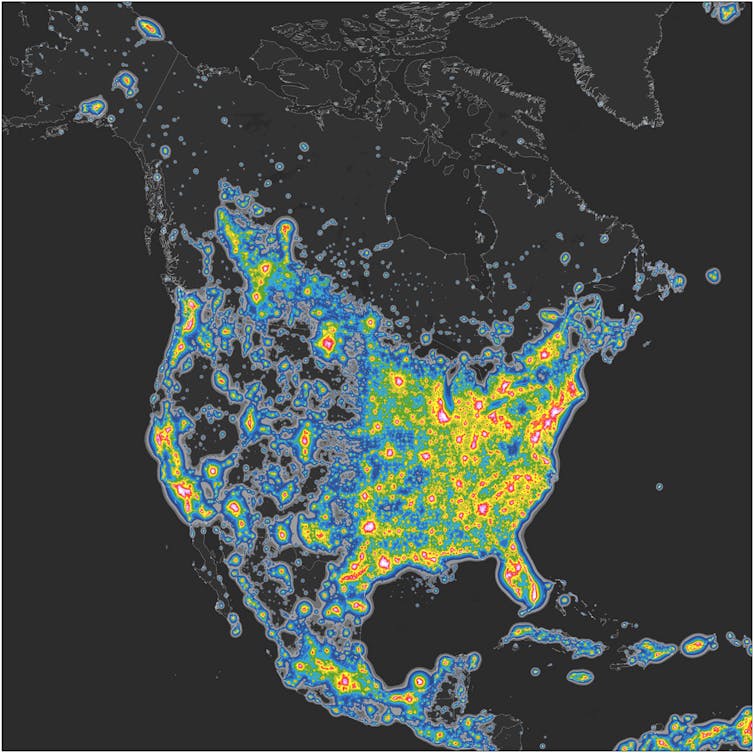

Map of North America’s artificial sky brightness, as a ratio to the natural sky brightness.

Falchi et al., Science Advances (2016), CC BY-NC

Hot science in the cold, dark night

While orbiting telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope or the James Webb Space Telescope give researchers a unique view of the cosmos – particularly because they can see light blocked by the Earth’s atmosphere – ground-based telescopes also continue to drive cutting-edge discovery.

Telescopes on the ground capture light with gigantic and precise focusing mirrors that can be 20 to 35 feet (6 to 10 meters) wide. Moving all astronomical observations to space to escape light pollution would not be possible, because space missions have a much greater cost and so many large ground-based telescopes are already in operation or under construction.

Around the world, there are 17 ground-based telescopes with primary mirrors as big or bigger than Webb’s 20-foot (6-meter) mirror, and three more under construction with mirrors planned to span 80 to 130 feet (24 to 40 meters).

The newest telescope starting its scientific mission right now, the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, has a mirror with a 28-foot diameter and a 3-gigapixel camera. One of its missions is to map the distribution of dark matter in the universe.

To do that, it will collect a sample of 2.6 billion galaxies. The typical galaxy in that sample is 100 times fainter than the natural glow in the nighttime air in the Earth’s atmosphere, so this Rubin Observatory program depends on near-total natural darkness.

The more light pollution there is, the fewer stars a person can see when looking at the same part of the night sky. The image on the left depicts the constellation Orion in a dark sky, while the image on the right is taken near the city of Orem, Utah, a city of about 100,000 people.

jpstanley/Flickr, CC BY

Any light scattered at night – road lighting, building illumination, billboards – would add glare and noise to the scene, greatly reducing the number of galaxies Rubin can reliably measure in the same time, or greatly increasing the total exposure time required to get the same result.