In a world where sports are dominated by youth and speed, some athletes in their late 30s and even 40s are not just keeping up – they are thriving.

Novak Djokovic is still outlasting opponents nearly half his age on tennis’s biggest stages. LeBron James continues to dictate the pace of NBA games, defending centers and orchestrating plays like a point guard. Allyson Felix won her 11th Olympic medal in track and field at age 35. And Tom Brady won a Super Bowl at 43, long after most NFL quarterbacks retire.

The sustained excellence of these athletes is not just due to talent or grit – it’s biology in action. Staying at the top of their game reflects a trainable convergence of brain, body and mindset. I’m a performance scientist and a physical therapist who has spent over two decades studying how athletes train, taper, recover and stay sharp. These insights aren’t just for high-level athletes – they hold true for anyone navigating big life changes or working to stay healthy.

Increasingly, research shows that the systems that support high performance – from motor control to stress regulation, to recovery – are not fixed traits but trainable capacities. In a world of accelerating change and disruption, the ability to adapt to new changes may be the most important skill of all. So, what makes this adaptability possible – biologically, cognitively and emotionally?

LeBron James, a forward for the Los Angeles Lakers, has spent decades training his court awareness so he can make snap decisions under pressure.

AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack

The amygdala and prefrontal cortex

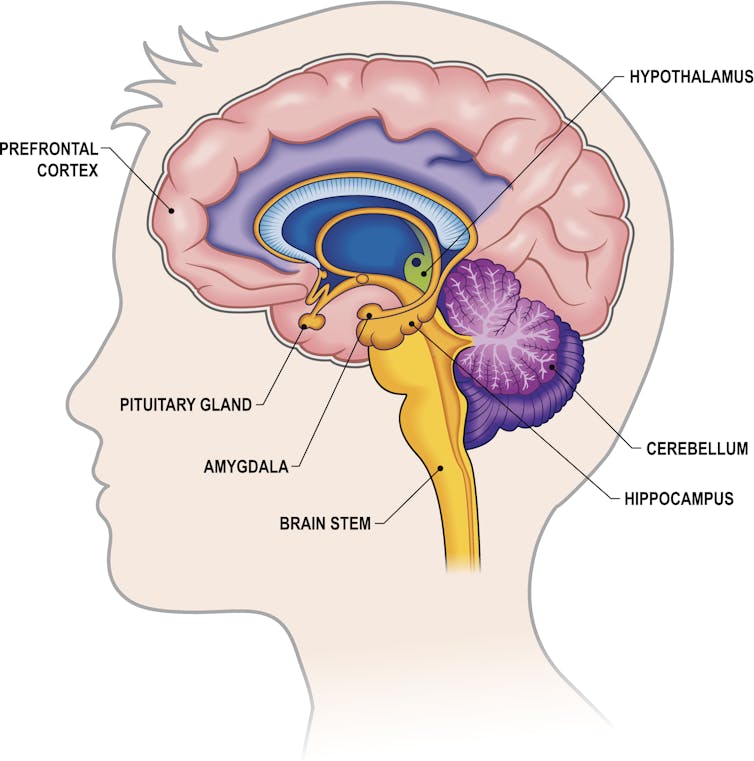

Neuroscience research shows that with repeated exposure to high-stakes situations, the brain begins to adapt. The prefrontal cortex – the region most responsible for planning, focus and decision-making – becomes more efficient in managing attention and making decisions, even under pressure.

During stressful situations, such as facing match point in a Grand Slam final, this area of the brain can help an athlete stay composed and make smart choices – but only if it’s well trained.

The prefrontal cortex is at the front of the brain, and the amygdala is near the brain stem.

jambojam/iStock via Getty Images

In contrast, the amygdala, our brain’s threat detector, can hijack performance by triggering panic, freezing motor responses or fueling reckless decisions. With repeated exposure to high-stakes moments, elite athletes gradually reshape this brain circuit.

They learn to tune down amygdala reactivity and keep the prefrontal cortex online, even when the pressure spikes. This refined brain circuitry enables experienced performers to maintain their emotional control.

Creating a brain-body loop

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, is a molecule that supports adapting to changes quickly. Think of it as fertilizer for the brain. It enhances neuroplasticity: the…