A moose in Minnesota stumbles onto the road. She circles, confused and dazed, unable to orient herself or recognize the danger of an oncoming semitruck. What kills her is the impact of 13 tons of steel, but what causes her death is more complicated. Tunneling through her brain is a worm that doomed both of them to die.

Commonly known as the brain worm, Parelaphostrongylus tenuis is a parasitic nematode that infects a large range of wild and domestic herbivores, such as moose and elk. The worm can migrate into the brain of unsuspecting hosts, where it may cause catastrophic disease and death.

While the Minnesotan moose is a hypothetical example, this worm has caused serious neurological impairments in many animals. The symptoms of the disease can vary, from disorientation and circling to paralysis across the animal’s back end, the inability to stand up and potentially death.

As parasitologists, we’ve been studying the effects these worms can have on moose populations in Minnesota. Tracking the spread of parasites and diseases in wild moose populations helps wildlife managers preserve those populations and reduce the spread to other animals or livestock.

While white-tailed deer can harbor these parasites without having any symptoms of disease, the worm can wreak havoc on populations of ungulates, like moose and elk, that aren’t adapted to the parasite. And tracking the disease in the wild isn’t easy.

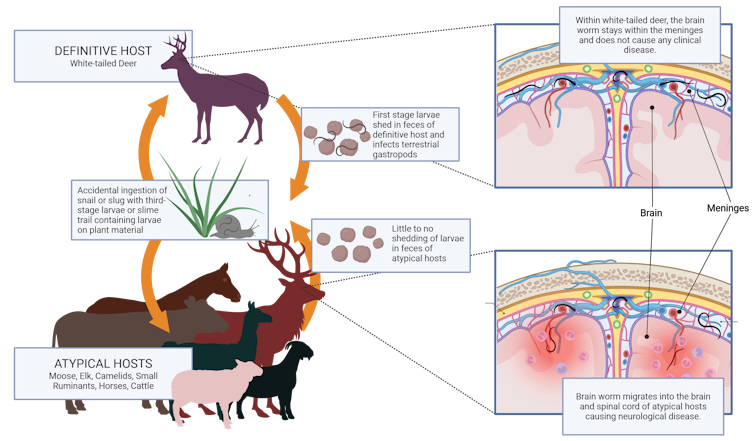

The disease cycle

White-tailed deer harboring these parasites may shed the worms into their environment when they defecate. Snails and slugs then take up this larva, where it develops inside them to the point where it’s capable of infecting other types of deer, moose, elk and cattle.

The brain worm life cycle.

Jesse Richards

For us as parasitologists, the biggest challenge lies in detecting the disease before it irreversibly damages its host. Only white-tailed deer pass the parasite in their feces. This means we can’t detect this parasite by analyzing the poop of moose, or any animal, besides the white-tailed deer.

Once an animal is visibly sick, it’s too late for it to make a recovery. Only after their death can we recover the body and identify the parasite from where it’s embedded in the brain or spinal cord.

Even once we’ve recovered the body, finding a single, threadlike worm within the entirety of a moose or elk’s nervous system is time-consuming and often futile. Usually, wildlife biologists can only tell that an animal was infected by looking at microscopic evidence that suggests a parasite migrated through the central nervous system, and by analyzing DNA fragments left behind by the worm.

The first stage larvae of a Parelaphostrongylus tenuis worm.

Diagnostic confusion

To make things even harder, disease signs caused by other worms, like the arterial worm Elaeophora schneideri, look similar…