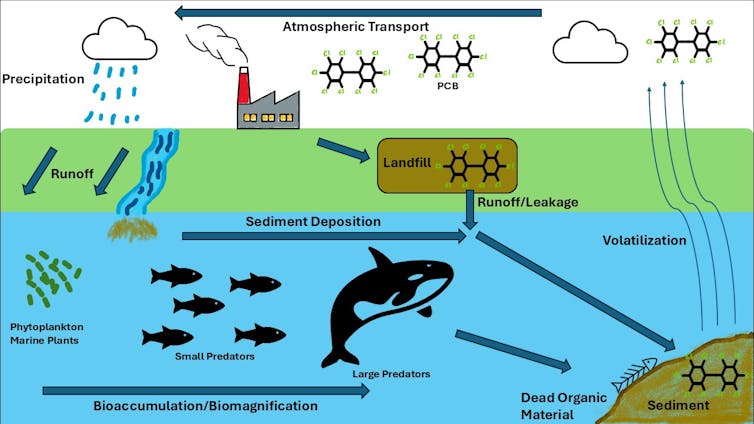

Polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, a class of fire-resistant industrial chemicals, were widely used in electrical transformers, oils, paints and even building materials throughout the 20th century. However, once scientists learned PCBs were accumulating in the environment and posed a cancer risk to humans, new PCB production was banned in the late 1970s, although so-called legacy PCBs remain in use.

Unfortunately, banned isn’t the same as gone, which is where scientists like me come in. PCBs remain in the environment to this day, as they are considered a class of “forever chemicals” that attach to soil and sediment particles that settle at the bottom of bodies of water. They do not easily break down once in the environment because they are inert and do not typically bind or react with other molecules and chemicals.

PCBs can enter the environment through landfill runoff and cycle through land, air and water.

David Ramotowski

Some sediments can release PCBs into water and air. As a result, they have spread all over the world, even to the Arctic and the bottom of the ocean, thousands of miles from any known source.

Airborne PCBs particularly affect people living near contaminated sites. Current cleanup methods involve either transferring contaminated sediment to a chemical waste landfill or incinerating it, which is expensive and could unintentionally release more PCBs into the air.

I’m a Ph.D. candidate in civil and environmental engineering at the University of Iowa. My research seeks to prevent PCBs from getting into the air by using bacteria to break down the PCBs directly at contaminated sites – without needing to remove and dispose of the sediment.

Introducing bacteria to the environment

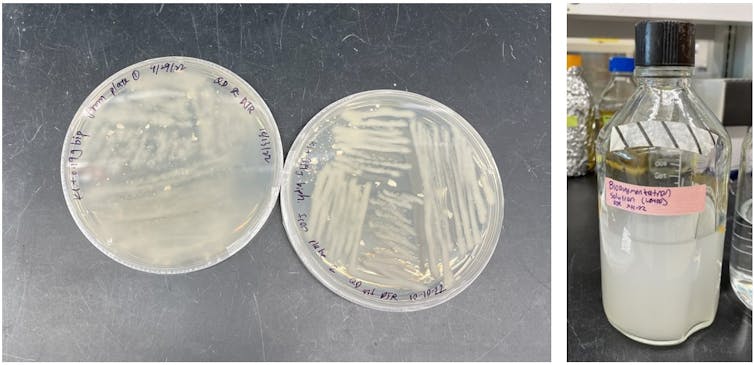

I work with a bacteria species called Paraburkholderia xenovorans LB400, or LB400 for short. First discovered in 1985 in a New York chemical waste landfill, LB400 has since become one of the most well-known aerobic, or oxygen-using, PCB-degrading bacteria, able to work in both freshwater and saltwater sediments. LB400 can effectively break down the lighter PCBs that are more likely to end up in the air and pose a threat to nearby communities.

The bacteria Paraburkholderia xenovorans LB400 on a petri dish, left, and in its liquid state, right.

David Ramotowski

LB400 degrades PCBs by adding oxygen atoms to one side of a PCB molecule. This ultimately results in the PCB splitting in half and producing compounds called chlorobenzoates, along with other organic acids. Other bacteria can degrade these compounds or turn them into carbon dioxide. My colleagues and I plan to measure them in our future work to ensure that these byproducts do not pose a threat to LB400 and other life forms.

However, LB400 cannot survive for very long in most PCB-polluted environments, so it can’t yet clean up these chemicals at a larger scale. For example, in some places with…