Every day, your immune system performs a delicate balancing act, defending you from thousands of pathogens that cause disease while sparing your body’s own healthy cells. This careful equilibrium is so seamless that most people don’t think about it until something goes wrong.

Autoimmune diseases such as Type 1 diabetes, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis are stark reminders of what happens when the immune system mistakes your own cells as threats it needs to attack. But how does your immune system distinguish between “self” and “nonself”?

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine honors three scientists – Shimon Sakaguchi, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell – whose groundbreaking discoveries revealed how your immune system maintains this delicate balance. Their work on two key components of immune tolerance – regulatory T cells and the FOXP3 gene – transformed how researchers like me understand the immune system, opening new doors for treating autoimmune diseases and cancer.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine was awarded to Shimon Sakaguchi, Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell.

How immune tolerance works

While the immune system is designed to recognize and eliminate foreign invaders such as viruses and bacteria, it must also avoid attacking the body’s own tissues. This concept is called self-tolerance.

For decades, scientists thought self-tolerance was primarily established in the parts of the body that make immune cells, such as the thymus for T cells and the bone marrow for B cells. There, newly created immune cells that attack “self” are eliminated during development through a process called central tolerance.

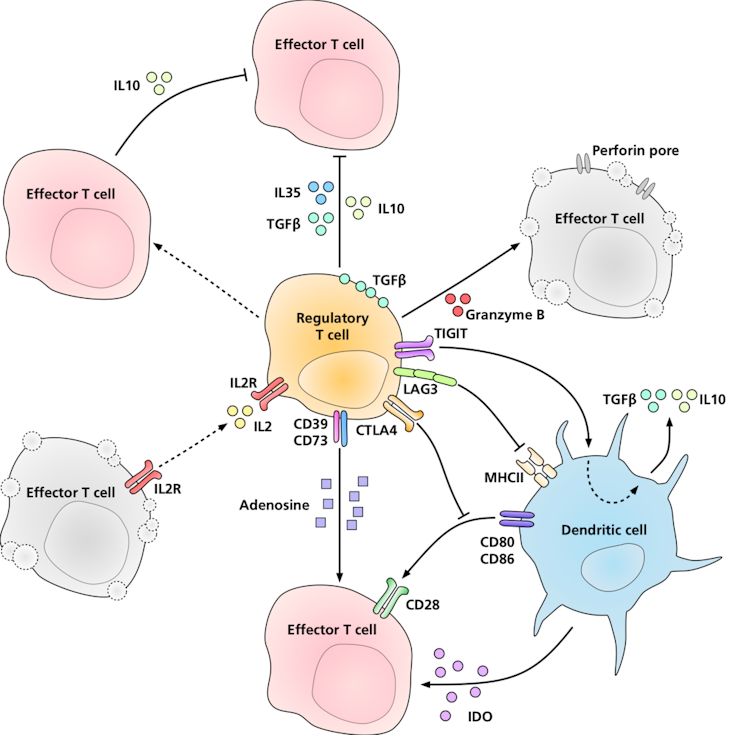

However, some of these self-reactive immune cells escape this process of elimination and are released into the rest of the body. Sakaguchi’s 1995 discovery of a new class of immune cells, called regulatory T cells, or Tregs, revealed another layer of protection: peripheral tolerance. These cells act as security guards of the immune system, patrolling the body and suppressing rogue immune responses that could lead to autoimmunity.

Regulatory T cells suppress immune responses using a variety of molecular signals.

Giwlz/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

While Sakaguchi identified the cells, Brunkow and Ramsdell in 2001 uncovered the molecular key that controls them. They found that mutations in a gene called FOXP3 caused a fatal autoimmune disorder in mice. They later showed that similar mutations in humans lead to immune dysregulation and a rare and severe autoimmune disease called IPEX syndrome, short for immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome. This disease results from missing or malfunctioning regulatory T cells.

In 2003, Sakaguchi confirmed that FOXP3 is essential for the development of regulatory T cells. FOXP3 codes for a type of protein called a