Envision a time when hundreds of spacecraft are exploring the solar system and beyond. That’s the future that NASA’s ESCAPADE, or Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers, mission will help unleash: one where small, low-cost spacecraft enable researchers to learn rapidly, iterate, and advance technology and science.

The ESCAPADE mission launched on Nov. 13, 2025 on a Blue Origin New Glenn rocket, sending two small orbiters to Mars to study its atmosphere. As aerospace engineers, we’re excited about this mission because not only will it do great science while advancing the deep space capabilities of small spacecraft, but it also will travel to the red planet on an innovative new trajectory.

The ESCAPADE mission is actually two spacecraft instead of one. Two identical spacecraft will take simultaneous measurements, resulting in better science. These spacecraft are smaller than those used in the past, each about the size of a copy machine, partly enabled by an ongoing miniaturization trend in the space industry. Doing more with less is very important for space exploration, because it typically takes most of the mass of a spacecraft simply to transport it where you want it to go.

The ESCAPADE mission logo shows the twin orbiters.

TRAX International/Kristen Perrin

Having two spacecraft also acts as an insurance policy in case one of them doesn’t work as planned. Even if one completely fails, researchers can still do science with a single working spacecraft. This redundancy enables each spacecraft to be built more affordably than in the past, because the copies allow for more acceptance of risk.

Studying Mars’ history

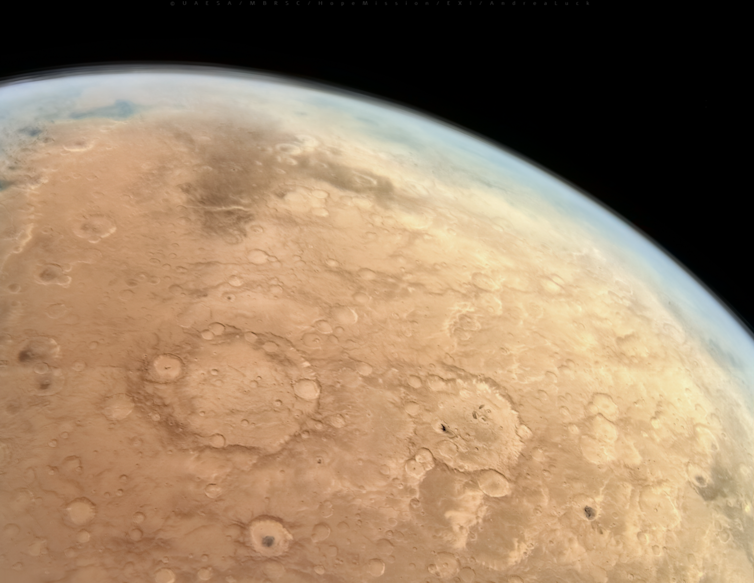

Long before the ESCAPADE twin spacecraft Blue and Gold were ready to go to space – billions of years ago, to be more precise – Mars had a much thicker atmosphere than it does now. This atmosphere would have enabled liquids to flow on its surface, creating the channels and gullies that scientists can still observe today.

But where did the bulk of this atmosphere go? Its loss turned Mars into the cold and dry world it is today, with a surface air pressure less than 1% of Earth’s.

Mars also once had a magnetic field, like Earth’s, that helped to shield its atmosphere. That atmosphere and magnetic field would have been critical to any life that might have existed on early Mars.

Today, Mars’ atmosphere is very thin. Billions of years ago, it was much thicker.

UAESA/MBRSC/HopeMarsMission/EXI/AndreaLuck, CC BY-ND

ESCAPADE will measure remnants of this magnetic field that have been preserved by ancient rock and study the flow and energy of Mars’ atmosphere and how it interacts with the solar wind, the stream of particles that the sun emits along with light. These measurements will help to reveal where the atmosphere went and how quickly Mars is still losing it today.

Weathering space on a budget

Space is not a…