Naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan, is one of the most important drugs in the United States’ fight against the opioid crisis. It reverses an opioid overdose nearly instantly, restarting breathing in a person who was unresponsive moments before and on the brink of death. To bystanders witnessing it being administered, naloxone can appear almost supernatural.

Although the Food and Drug Administration approved naloxone for medical use in 1971 and for over-the-counter purchase in 2023, exactly how it works is still unclear. Researchers know naloxone acts on opioid receptors, a family of proteins responsible for the body’s response to pain. When opioids such as morphine and fentanyl bind to these receptors, they produce not only pain relief and euphoria but also dangerous side effects. Naloxone competes with opioids for access to these receptors, preventing the drugs from triggering effects in the body. How it does this at the molecular level, however, has been an ongoing question.

In our recently published research in the journal Nature, my team and I were able to provide some definitive evidence of how naloxone works by capturing images of it in action for the first time.

Knowing how to use naloxone can save lives.

Biology of opioids

To better grasp how naloxone works, it’s helpful to first zoom in on the biology behind opioids.

One member of the family of opioid receptors, MOR – short for µ-opioid receptor – is a central player in regulating the body’s response to pain. It sits on the surface of neurons, mostly in the brain and spinal cord, and acts as a communication hub.

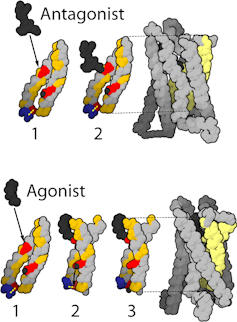

When an opioid – such as an endorphin, the body’s natural painkillers – interacts with MOR, it changes the structure of the receptor. This change in shape allows what’s called a G protein to bind to the receptor and trigger a signal to the rest of the body to reduce pain, induce pleasure, or – in the case of overdose – dangerously slow breathing and heart rate.

When a molecule binds to the µ-opioid receptor, it changes its structure and elicits an effect. Antagonists like naloxone inactivate the µ-opioid receptor, while agonists like fentanyl activate it.

Bensaccount/Wikimedia Commons

In everyday terms, MOR is like a lock on the outside of the cell. The G protein is the mechanism inside the lock that turns when the correct key – in this case, an endorphin or a drug like fentanyl – goes in. For decades, scientists believed that an opioid’s ability to enable this signaling cascade was linked to how effectively it reshaped the structure of the receptor – essentially, whether the lock could open wide enough for the internal mechanism of the G-protein to engage.

Yet, recent research – including our work – has revealed that the critical step to how opioids work is not how wide they open the lock but how well the…