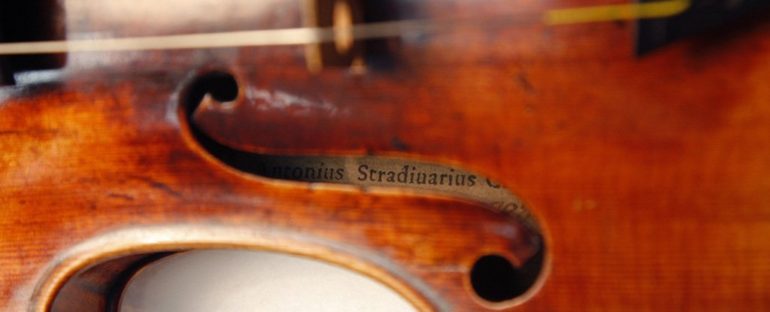

The antique violins made by Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri in the 17th and 18th centuries are still very much sought after by modern-day musicians. Now, a new study reveals one of the hidden reasons why: the chemical treatments applied to the wood of the instruments.

As it turns out, it’s not just the quality of the craftsmanship that creates the superior sound of these classic violins – called Cremonese violins after the area where they were produced – but also the way the wood was processed.

This latest study focussed particularly on the soundboard of the violin, the part that’s most crucial to the acoustic output of the instrument. Stradivari and Guarneri soundboards are relatively thin and light by modern day standards, and it’s here that the chemicals would have originally been applied.

“This new study reveals that Stradivari and Guarneri had their own individual proprietary method of wood processing, to which they could have attributed a considerable significance,” says biochemist Joseph Nagyvary, from Texas A&M University.

“They could have come to realize that the special salts they used for impregnation of the wood also imparted to it some beneficial mechanical strength and acoustical advantages.”

The idea that chemical processing is the reason Stradivari and Guarneri violins stand out has been explored by Nagyvary and colleagues before, but this new work goes further into identifying the sort of substances that were probably used by the master violin makers.

Using a combination of techniques involving spectroscopy (studying materials using light and radiation), microscopic analysis and chemical techniques, the team was able to identify borax, zinc and copper sulfates, alum, and lime water as being part of the treatment mix.

The overall purpose of these applications would have been to preserve the wood and tweak the acoustics of the violin, the researchers say. Borax, for example, has been used as a preservative since the time of the ancient Egyptians.

The chemicals were found all over and running through the wood, so these weren’t just surface treatments. It’s likely that the fresh spruce planks used for the soundboards were soaked in a special chemical mix for some time before being used.

“The presence of these chemicals all points to collaboration between the violin makers and the local drugstore and druggist at the time,” says Nagyvary.

“Both Stradivari and Guarneri would have wanted to treat their violins to prevent worms from eating away the wood because worm infestations were very widespread at that time.”

In an era without patents and the subsequent protections against competition, the makers of the Cremonese violins would have been very keen to keep their processes secret – the treatments would not have been visible to the naked eye, and the secrecy is perhaps one reason that these techniques died out.

Only a few hundred instruments from each craftsman now remain in existence, and they can sell for tens of millions of dollars when they change hands.

Now we know part of the reason why – though further research will be required to work out the exact chemical mix used and how it interacts with the wood, potentially altering the acoustics.

“All of my research over many years has been based on the assumption that the wood of the great masters underwent an aggressive chemical treatment, and this had a direct role in creating the great sound of the Stradivari and the Guarneri,” says Nagyvary.

The results have been published in Angewandte Chemie.