If the omicron variant of the coronavirus is different enough from the original variant, it’s possible that existing vaccines won’t be as effective as they have been. If so, it’s likely that companies will need to update their vaccines to better fight omicron. Deborah Fuller is a microbiologist who has been studying mRNA and DNA vaccines for over two decades. Here she explains why vaccines might need to be updated and what that process would look like.

1. Why might vaccines need to be updated?

Basically, it’s a question of whether a virus has changed enough so that antibodies created by the original vaccine are no longer able to recognize and fend off the new mutated variant.

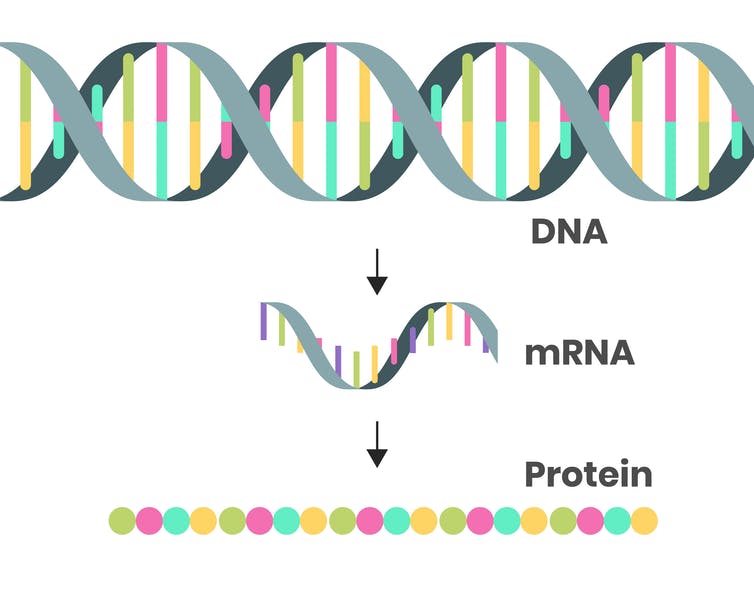

Coronaviruses use spike proteins to attach to ACE-2 receptors on the surface of human cells and infect them. All mRNA COVID-19 vaccines work by giving instructions in the form of mRNA that direct cells to make a harmless version of the spike protein. This spike protein then induces the human body to produce antibodies. If a person is then ever exposed to the coronavirus, these antibodies bind to the coronavirus’s spike protein and thus interfere with its ability to infect that person’s cells.

The omicron variant contains a new pattern of mutations to its spike protein. These changes could disrupt the ability of some – but probably not all – of the antibodies induced by the current vaccines to bind to the spike protein. If that happens, the vaccines could be less effective at preventing people from getting infected by and transmitting the omicron variant.

2. How would a new vaccine be different?

Existing mRNA vaccines, like those made by Moderna or Pfizer, code for a spike protein from the original strain of coronavirus. In a new or updated vaccine, the mRNA instructions would encode for the omicron spike protein.

By swapping out the genetic code of original spike protein for the one from this new variant, a new vaccine would induce antibodies that more effectively bind the omicron virus and prevent it from infecting cells.

People already vaccinated or previously exposed to COVID-19 would likely need only a single booster dose of a new vaccine to be protected not only from the new strain but also other strains that may be still in circulation. If omicron emerges as the dominant strain over delta, then those who are unvaccinated would only need to receive 2-3 doses of the updated vaccine. If delta and omicron are both in circulation, people would likely get a combination of the current and updated vaccines.

By changing the mRNA sequence in a vaccine, researchers can change the antibody producing protein it encodes for to better match new variants.

Alkov/iStock via Getty Images

3. How do scientists update a vaccine?

To make an updated mRNA vaccine, you need two ingredients: the genetic sequence of the spike protein from a new variant of concern and a DNA template that would be used to build the…