Male pheromones just might be the fountain of youth for aging female animals’ eggs, according to a new Northwestern University study.

In the new study, researchers used the tiny transparent roundworm C. elegans, a well-established model organism commonly used in biology research. Exposure of female roundworms to male pheromones slowed down the aging of the females’ egg cells, resulting in healthier offspring.

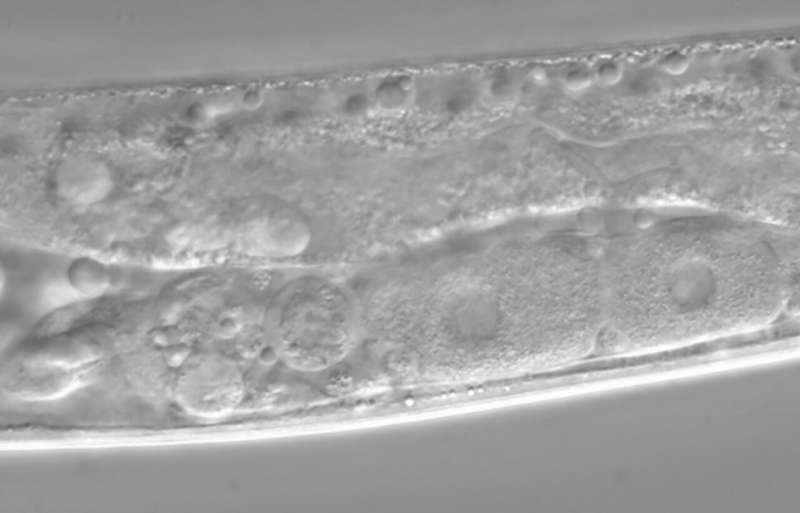

Not only did the exposure decrease embryonic death by more than twofold, it also decreased chromosomal abnormalities in surviving offspring by more than twofold. Under the microscope, egg cells also looked younger and healthier, rather than tiny and misshapen, which is common with aging.

The researchers believe this finding potentially could lead to pharmacological interventions that would combat infertility issues in humans by improving egg cell quality and delaying the onset of reproductive aging.

“Reproductive aging affects everyone,” said Northwestern’s Ilya Ruvinsky, who led the study. “One of the first signs of biological aging is the decreased quality of reproductive cells, which causes reduced fertility, increased incidence of fetal defects including miscarriages, and eventually loss of fertility. By all criteria we could think of, male pheromones made the eggs better.”

The paper was published this week (May 16) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Ruvinsky is a research associate professor of molecular biosciences at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. Erin Aprison, a research associate in Ruvinsky’s laboratory, is the paper’s first author. Svetlana Dzitoyeva and David Angeles-Albores are paper co-authors.

Shifting energy to reproduction

To conduct the study, the team aged female roundworms in the presence of a pheromone that is normally produced by male roundworms. The researchers saw that egg quality in females exposed to the pheromone was higher than in control roundworms that did not encounter the pheromone.

This image contrasts relatively normal oocytes (at the bottom right) with abnormally shapped ones (bottom left). © Ilya Ruvinsky/Northwestern University

Although continuous exposure to male pheromones worked best, even shorter exposure improved overall egg quality. Ruvinsky believes this result can be explained by the animals’ “shifting energy budgets.”

Acting outside the body, pheromones are chemicals that animals produce and release to elicit social responses from other members of their species. According to Ruvinsky, pheromones also inform animals about how to budget their finite energy.

When conditions are not conducive to reproduction, female animals will spend resources and energy maintaining their overall body health, including muscles, neurons, intestines and other nonreproductive organs. Sensing male pheromones triggers downstream signaling from the nervous system to the rest of the body, causing the female animals to shift their energy and resources to increasing reproductive health instead. The result? Better eggs but faster decay of the body.

“The pheromone tricks the female into sending help to her eggs and shortchanging the rest of her body,” Ruvinsky said. “It’s not all or nothing, but it’s shifting the balance.”

Salvaging recycled eggs

When female roundworms spent more energy on reproduction, they produced more egg cell precursors from stem cells. And, in a seemingly counterproductive move, most of these cells actually died. But Ruvinsky says this is not a mistake but a cleverly designed advantage.

“The majority of egg precursors die, and the spare parts are recycled to build better eggs,” he said. “We think that is essentially what’s happening. Production is increased. Most egg precursors die, and their parts are salvaged and recycled into a few, higher-quality eggs.”

Of course, there are unfortunate trade-offs. When female roundworms neglected the rest of their body to focus their energy on reproductive health, they were more likely to experience early death. Ruvinsky said this information, too, can advise future drug development for humans.

“The pheromones that roundworms use are not found in humans,” he said. “But the neurons they activate are very similar. We are working to design pharmacological interventions that manipulate these neurons to improve fertility while reducing the negative side effects. It remains to be seen, but it’s definitely worth trying.”

More information:

Erin Z. Aprison et al, A male pheromone that improves the quality of the oogenic germline, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2015576119

Provided by

Northwestern University

Citation:

New research finds that male pheromones may improve health of females’ eggs (2022, May 19)