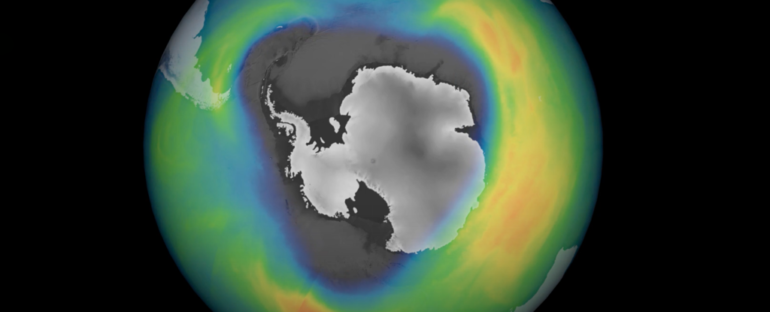

The hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica has expanded to one of its greatest recorded sizes in recent years.

In 2019, scientists revealed that the Antarctic ozone hole had hit its smallest annual peak since tracking began in 1982, but the 2020 update on this atmospheric anomaly – like other things this year – brings a sobering perspective.

“Our observations show that the 2020 ozone hole has grown rapidly since mid-August, and covers most of the Antarctic continent – with its size well above average,” explains project manager Diego Loyola from the German Aerospace Center.

New measurements from the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite show that the ozone hole reached its maximum size of around 25 million square kilometres (about 9.6 million square miles) on 2 October this year.

That puts it in about the same ballpark as 2018 and 2015’s ozone holes, which respectively recorded peaks of 22.9 and 25.6 million square kilometres.

“There is much variability in how far ozone hole events develop each year,” says atmospheric scientist Vincent-Henri Peuch from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

“The 2020 ozone hole resembles the one from 2018, which also was a quite large hole, and is definitely in the upper part of the pack of the last 15 years or so.”

As well as fluctuating from year to year, the ozone hole over Antarctica also shrinks and grows annually, with ozone concentrations inside the hole depleting when temperatures in the stratosphere become colder.

When this happens – specifically, when polar stratosphere clouds form at temperatures below –78°C (–108.4°F) – chemical reactions destroy ozone molecules in the presence of solar radiation.

“With the sunlight returning to the South Pole in the last weeks, we saw continued ozone depletion over the area,” Peuch says.

“After the unusually small and short-lived ozone hole in 2019, which was driven by special meteorological conditions, we are registering a rather large one again this year, which confirms that we need to continue enforcing the Montreal Protocol banning emissions of ozone depleting chemicals.”

The Montreal Protocol was a milestone in humanity’s environmental achievements, phasing out the manufacturing of harmful chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – chemicals previously used in refrigerators, packaging, and sprays – that destroy ozone molecules in sunlight.

While we now know that human action on this front is helping us to fix the Antarctic ozone hole, the ongoing fluctuations from year to year show that the healing process will be long.

A 2018 assessment by the World Meteorological Organisation found that ozone concentrations above Antarctica would return to relatively normal pre-1980s levels by about 2060. To realise that goal, we have to stick to the protocol and ride out the bumps, like the one we’re seeing this year.

While 2020’s maximum peak isn’t the largest on record – that was seen back in 2000, with a 29.9 million square kilometre hole – it is still significant, with the hole also being one of the deepest in recent years.

Researchers say the 2020 event has been driven by a strong polar vortex: a wind phenomenon keeping stratospheric temperatures above Antarctica cold.

In contrast, warmer temperatures last year were what brought about 2019’s record-low ozone hole size, as scientists explained back then.

“It’s important to recognise that what we’re seeing [in 2019] is due to warmer stratospheric temperatures,” Paul Newman, the chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, said at the time.

“It’s not a sign that atmospheric ozone is suddenly on a fast track to recovery.”

While there may be no fast track, and we can likely expect a few more scary peaks in the years ahead, the Montreal Protocol has our back. We’re going to get there one day if we hold true.