In the hands of a trained archeologist, a well-preserved grave can be read like an obituary, detailing the health, death, travels and even fortunes of a life long gone.

Advances in technology have been pushing the limits on how well-preserved a body needs to be in order for experts to extract a biography. In the case of one young Bronze Age woman in what is now central Hungary, not even cremation could hide her tragic tale.

Researchers from institutions in Italy and Hungary have analyzed numerous samples of human remains and artefacts uncovered in a 4,000-year-old cemetery near the Hungarian city of Szigetszentmiklós.

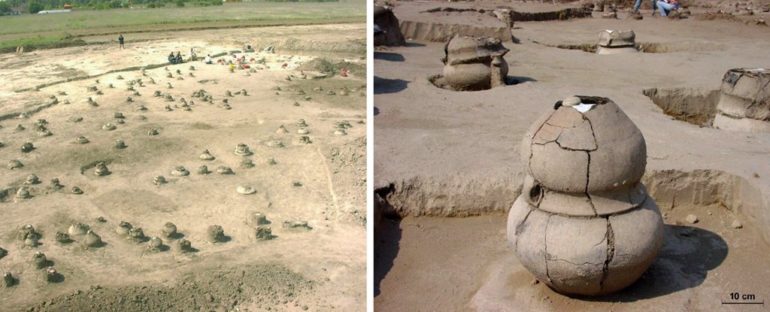

Consisting of hundreds of clay pots buried half a kilometer from the shore of the river Danube, the ‘urnfield’ cemetery preserves a trove of archeological data representing a long lost culture known as the Vatya.

The little we currently know of the Vatya is based on a scattering of fortified structures and cemeteries of cremated bodies buried in ceramic urns. It’s barely enough to give an insight into a people who occupied the Danube basin for about half a millennia starting roughly 2100 BCE.

The largest of those urnfields is a site near Szigetszentmiklós, uncovered during a rescue excavation prior to the construction of a new supermarket.

In total, 525 burials were found inside half a hectare (about an acre), mostly consisting of bone fragments, ash, and occasional grave goods made of ceramic or bronze.

The researchers took 41 samples from 29 of the burials, which included 26 urn cremations, and ran a variety of laboratory tests and measures to develop a clearer picture of who these people were.

One of those urns stood out from the rest. Coded gravesite 241, it contained more luxurious items that included a golden hair ring and a bronze neck ring, as well as two bone pins.

(Cavazzuti et al., PLOS ONE, 2021, CC-BY 4.0)

Above: Bronze neck-ring, gold hair-ring, bone pins/needles.

Even 241’s urn contained signs of the respect her community held, its design uniquely reflecting an early Vatya motif.

Among its bone fragments were also signs that the occupant – a female in her late 20s or early 30s – wasn’t buried alone. Two tiny infants, barely fetuses of around 30 weeks’ gestation, went into the grave with her.

Where most of the urns contained a mere portion of the deceased’s cremated body, the contents of 241 were comparatively more complete, almost as if an extraordinary level of care had been taken to collect every tiny fragment from the funerary pyre prior to burial.

Above: The woman’s bones (left), and those of her fetuses (right).

Though fragmented, her body still contained tiny details on her life history that could be revealed through an analysis of its isotopes.

Her molars, for example, contain layers of material called dentine which capture significant biographical events as a chemical signature. The conical part of her femur would have been remodeled at a standard rate over the years, preserving signs of nutrition and movement.

Measuring these signatures helped the researchers develop a picture of a woman who came from afar when she was a child of somewhere around 8 to 13 years of age, possibly having been born in Southern Moravia – what is today the Czech Republic – if not the upper Danube.

Similar analyses of the remains in other urns reveal her integration wasn’t unusual, with other women also coming from various places well outside the burial site’s locality.

We might imagine this esteemed young woman marrying into the respected higher ranks of the Vatya community, holding onto her heirloom neck ring as an emblem of her distant upbringing; her bone clothing pins and hair ring given as gifts welcoming her to her new home.

Tragically, she would pass away in her prime, pregnant with twins. For all her remains can tell us, we can only guess if her death was a consequence of an early birth, or something else entirely.

The emotional tale of number 241’s life aside, it’s remarkable that a few burned remains can tell us so much about the Vatya’s culture.

From a jumble of bones we can find traces of women journeying in from afar to create distant ties, reinforcing allegiances perhaps, but almost certainly affecting the power and politics of an age long gone.

Just how many tales are still out there, waiting to be translated by the right technology?

This research was published in PLOS One.