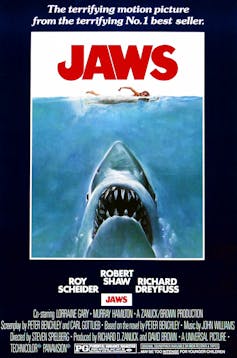

The summer of 1975 was the summer of “Jaws.”

The movie was adapted from a novel by Peter Benchley.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The first blockbuster movie sent waves of panic and awe through audiences. “Jaws” – the tale of a killer great white shark that terrorizes a coastal tourist town – captured people’s imaginations and simultaneously created a widespread fear of the water.

To call Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece a creature feature is trite. Because the shark isn’t shown for most of the movie – mechanical difficulties meant production didn’t have one ready to use until later in the filming process – suspense and fear build. The movie unlocked in viewers an innate fear of the unknown, encouraging the idea that monsters lurk beneath the ocean’s surface, even in the shallows.

And because in 1975 marine scientists knew far less than we do now about sharks and their world, it was easy for the myth of the rogue shark as a murderous eating machine to take hold, along with the assumption that all sharks must be bloodthirsty, mindless killers.

People lined up to get scared by the murderous shark at the center of the ‘Jaws’ movie.

Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

But in addition to scaring many moviegoers that “it’s not safe to go in the water,” “Jaws” has over the years inspired generations of researchers, including me. The scientific curiosity sparked by this horror fish flick has helped reveal so much more about what lies beneath the waves than was known 50 years ago. My own research focuses on the secret lives of sharks, their evolution and development, and how people can benefit from the study of these enigmatic animals.

The business end of sharks: Their jaws and teeth

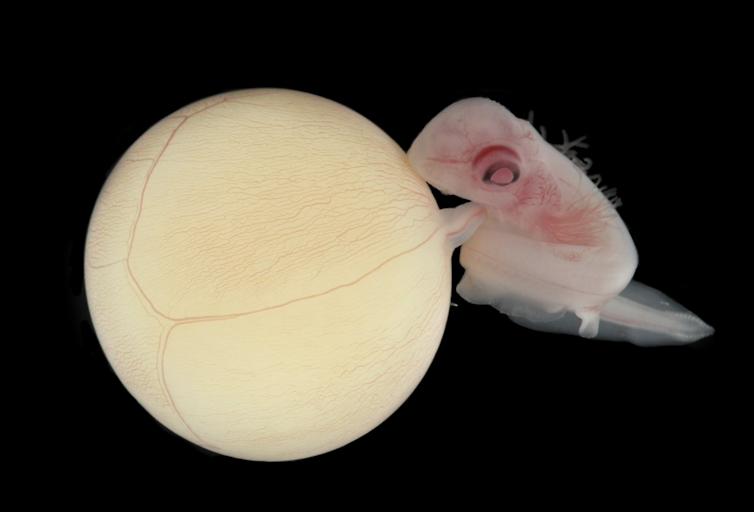

My own work has focused on perhaps the most terrifying aspect of these apex predators, the jaws and teeth. I study the development of shark teeth in embryos.

Small-spotted catshark embryo (Scyliorhinus canicula), still attached to the yolk sac. This is the stage when the teeth begin developing.

Ella Nicklin, Fraser Lab, University of Florida

Sharks continue to make an unlimited supply of tooth replacements throughout life – it’s how they keep their bite constantly sharp.

Hard-shelled prey, such as mollusks and crustaceans, from sandy substrates can be more abrasive for teeth, requiring quicker replacement. Depending on the water temperature, the conveyor belt-like renewal of an entire row of teeth can take between nine and 70 days, for example, in nurse sharks, or much longer in larger sharks. In the great white, a full-row replacement can take an estimated 250 days. That’s still an advantage over humans – we never regrow damaged or worn-out adult teeth.