Does the toothpaste Colddate infringe upon the trademark of Colgate? Some might think this is a no-brainer. But in a 2007 lawsuit between the two brands, Colgate-Palmolive lost on the grounds that the two brands were “similar” but not “substantially indistinguishable.”

Determining trademark infringement can often be challenging and fraught with controversy. The reason is that, at its core, a verdict for infringement requires proof that the two brands are confusingly similar. And yet the existing approach primarily relies on self-report, which is known to be vulnerable to biases and manipulation.

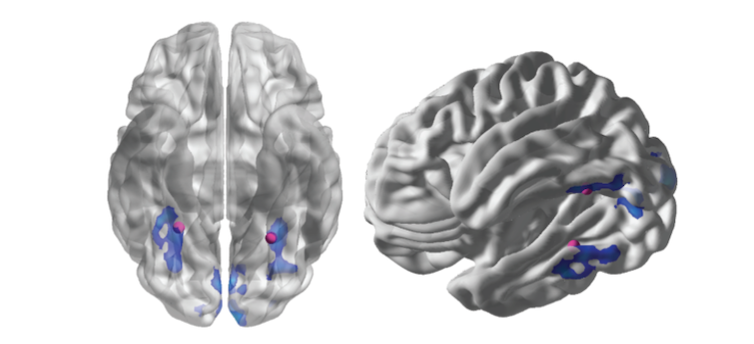

But this challenge also provides an interesting lens into the complex yet fascinating relationship between scientific evidence and legal practices. I am a marketing professor with a background in cognitive neuroscience, and one of my research interests is in using neuroscientific tools to study consumer behavior. In our recently published study, my colleagues and I demonstrated how looking directly into the brain may help solve the conundrum of how to measure similarity between trademarks.

Determining trademark infringement is messy

In most legal systems, trademark infringement decisions revolve around whether a “reasonable person” would find two trademarks similar enough to cause confusion. While this may sound straightforward and intuitive, judges have found it incredibly difficult to translate such a criterion into concrete guidance for legal decision-making. Many legal scholars have lamented the lack of a clear definition of a “reasonable person,” or what factors contribute to “similarity” and their relative importance.

This ambiguity is further compounded by the adversarial legal system in the U.S. and many other countries. In such a system, two opposing parties each hire their own attorneys and expert witnesses who present their own evidence. Often that evidence takes the form of consumer surveys conducted by an expert witness hired by a party, which can be susceptible to manipulation – for example, through the use of leading questions. Not surprisingly, plaintiffs are known to present surveys finding that two trademarks are similar, while defendants present competing surveys showing they are different.

This unfortunate situation arises largely because there is no legal gold standard about what types of background information survey respondents should receive, how the questions should be phrased and what criteria of “similarity” should be followed – all factors that can change the results substantially. For example, parties could include instructions on how respondents should evaluate similarity.

As a result, judges have developed some degree of cynicism. It is not uncommon that some simply discard the evidence from both sides and go with their own judgment – which could risk replacing one set of biases with another, despite their best intentions.